‘If they find us here, we’ll be punished’: RT report on ‘secret schools’ for girls in Afghanistan

“There is an underground project in Kabul called ‘Course in memoir writing for wounded girls.’ Would you be interested to see it?” I was asked last week.

These days, education for girls is probably the most ambiguous topic of Afghanistan’s new era. The Taliban is to some extent demonstrating its commitment to a medieval approach to women’s rights but is nevertheless inclined to compromise. Primary schools remain open, as do universities, though male and female students attend lectures separately, and the number of female lecturers has dramatically decreased since last August.

However, secondary schools remain inaccessible for girls, just as they were after the Taliban returned to power. On the first day of the new spring term, students above sixth grade were sent home “until further notice,” whatever that could imply. The Ministry of Education had received a decree from higher authorities, but there was no accompanying explanation. Some private schools still teach senior girls – but only if the owners of these schools are well-connected and do not need to fear retribution from the Taliban. In a few provinces of Afghanistan girls did not stop learning, but Kabul is not among them.

So-called “secret schools” became an alternative for those who sought to continue their studies. Run by teachers at their own risk in their homes or rooms rented in educational centers, these informal arrangements have in many places replaced formal education. So far, the Talibs have been condoning this practice, but nobody knows what may follow if they eventually embark on a more disciplinarian path.

The course I was invited to visit was created for the girls from the stricken Sayed Al-Shuhada school. Situated in the predominantly ethnically Hazara area of Dashte Barchi in the west of Kabul, the school was targeted by a terrorist attack last May. Although the previous government predictably blamed the attack on the Taliban, the latter denied involvement, and nobody ended up claiming responsibility.

A car bomb explosion followed by two IED blasts left 85 people dead and more than 160 wounded, no matter who the attacker was. The majority of the victims were girls from 12 to 20 years old – the car bomb went off in front of the school gate at the time of the second shift scheduled for females.

Who might be willing and brave enough to teach the survivors to record their memories in writing – and why?

Creative writing versus PTSD

One such person is Mr. Adib*. An elegant, clean-shaven young man who wears stylish Western clothes, he is the type that one could easily imagine tucked in a café in Tehran with a cup of coffee and a novel by Dostoevsky, but hardly in Taliban-ruled Kabul. Mr. Adib is in fact a big fan of this Russian novelist, and of the Persian classics, too, and is currently taking an online literature course at the University of Tehran. He is at the helm of the memoir course for the traumatized girls. During the lesson, Mr. Adib, who possesses a somewhat theatrical delivery, tosses out references to Ferdowsi’s ‘Shahnameh’, Jack London, and Sophocles. Unfortunately, his female colleague, also a university student, is now busy with her exams, so Mr. Adib teaches alone.

“I was in Iran on the day of the attack. When I heard about the blasts, I was mortified. Four of my brother's children were students at that school, and the thought that they might have been hurt was unbearable,” says Mr. Adib.

When he got back to Kabul, a local TV channel offered him to run a project aimed at helping the Sayed Al-Shuhada students overcome PTSD. Preparations took time, and the TV channel ended up closing, but the idea did not fade away. Twenty days after the fall of Kabul, Mr. Adib, doubtful about the future, held his first lesson in an educational center on the outskirts of the capital.

“Nobody knew how the Taliban would react, so we decided to keep this course a secret,” he explains. His main objective was to enable the girls to talk about their traumatizing experience and to have their memoirs written and published one day.

“The Afghan culture perceives pain as something shameful, something one must conceal. But I'm telling the girls there is nothing shameful in having dark days or talking about the dark days you had,” Mr. Adib says.

His family is proud of him, if slightly apprehensive. Clearly, for semi-literate village mullahs, a young man teaching creative writing to girls and lecturing them on philosophy is sinful and punishable under Sharia law, but the Talibs have not interrupted Mr. Adib's classes so far, and he hopes they never will. Instead, he is more worried about his students. At first, some girls could not handle the stress and cried in the classroom and ran back home. Even now, a few of them cannot bear the sight of armed people or loud, sudden sounds and might faint or have a massive panic attack if the Taliban track down Mr. Adib and show up at a lesson.

However, this Afghan John Keating is determined to continue, similar to his colleague from the ‘Dead Poets Society’. He sought purely to educate and elevate his students in unorthodox methods. The girls do not pay any fee. Instead, the course subsists on donations by Mr. Adib's friends, which allows him to pay the rent for the room and buy the books. As a result, all he can afford now is one two-hour lesson per week, essentially meaning he volunteers literally for the sake of art.

Teaching techniques and the search for meaning

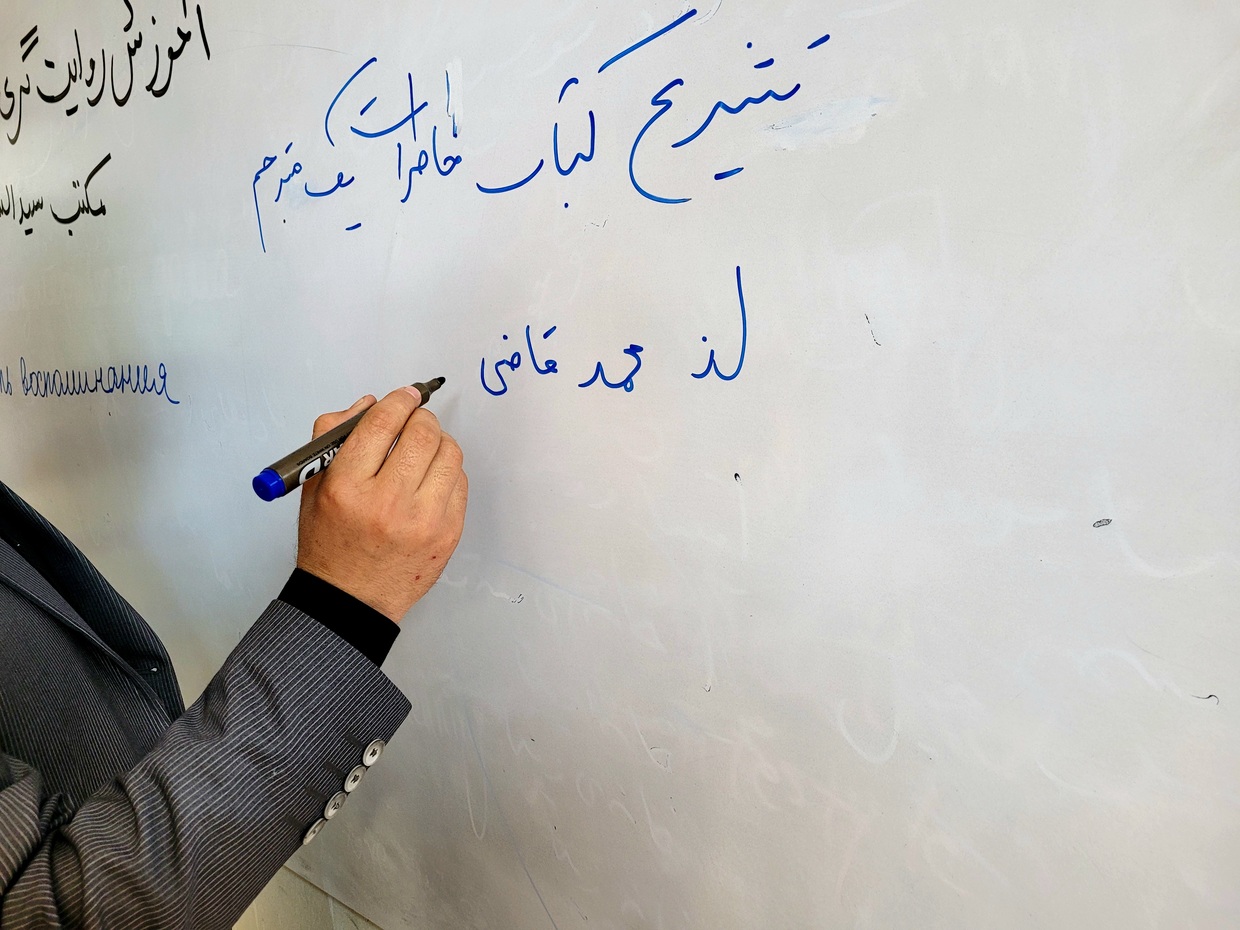

“A good reader makes a good writer,” says Mr. Adib, as he writes another quote on the blackboard.

‘Khateraat-e yek Motarjem’ (Memoirs of a Translator) is his latest choice for the students. Written by Mohammad Ghazi, a prominent Iranian writer and translator, the book helps expand vocabulary and develop critical thinking, Mr. Adib believes. Previously read and discussed was ‘Man’s Search for Meaning’ by Viktor Frankl, who survived several concentration camps in Nazi Germany and carried on his career as a psychiatrist and philosopher, thus making him an inspiration for the girls from Sayed Al-Shuhada, who are also no strangers to ordeals.

Mr. Adib also requests that the girls recount what they read at home and asks probing questions to make sure they understand everything, occasionally correcting their pronunciation (“Do not say ‘motarajem’, Tamana, it is motarjem.’” Please repeat after me.”) He also explains some basic terms of literary criticism and philology and gets back to writing (“You must always find a good title for your story; this is the first step. What is a story without a name? Nothing!”).

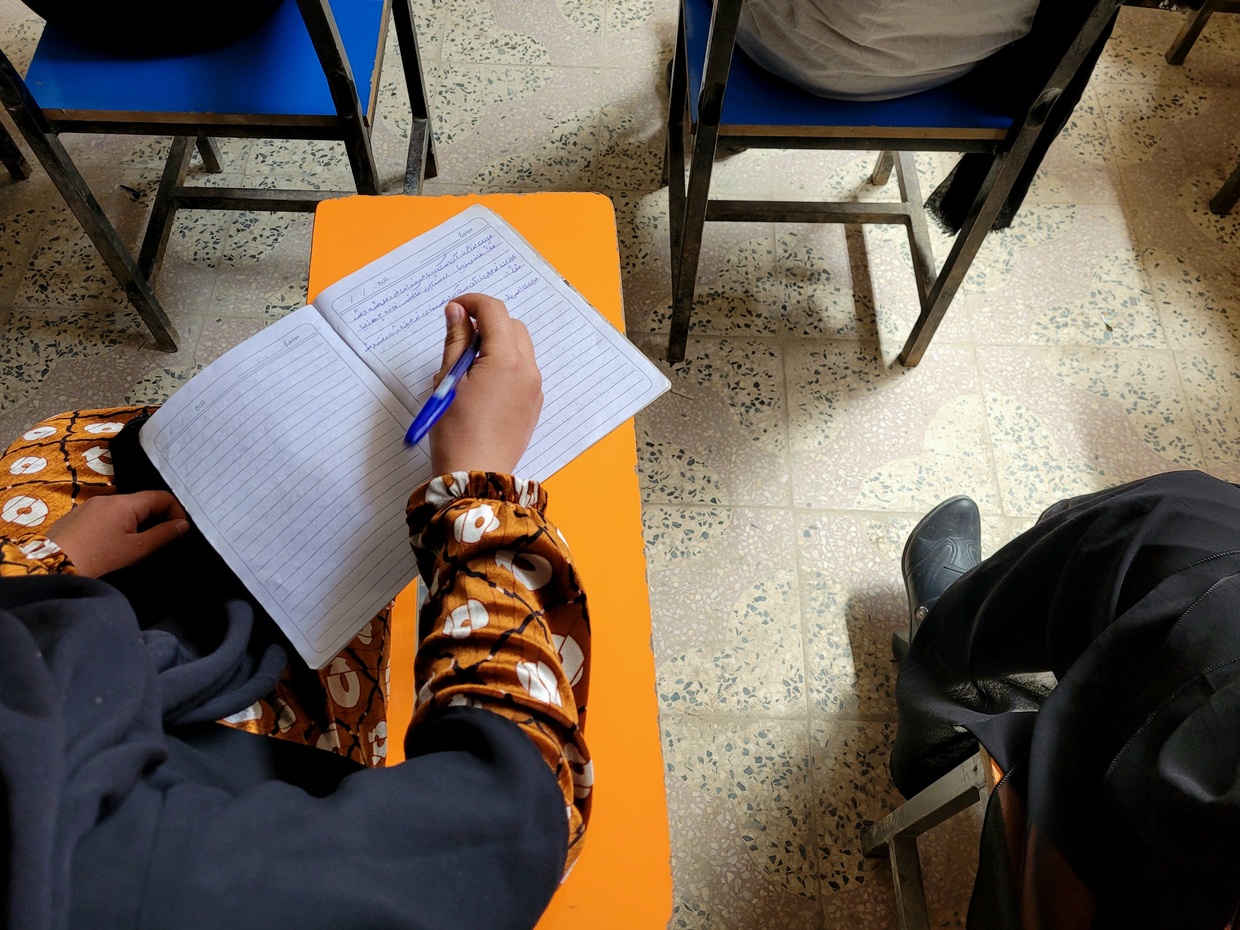

At every lesson, Mr. Adib gives his students a topic for an essay. Today, it was ‘Life’. The girls came forward to the blackboard and read their homework aloud.

“There are two essential things in our lives: One is hope, and the other is a goal. A person without hope is like a horse without a road; a person without hope is like a tree without roots. Sometimes it is hard to live; sometimes, it seems impossible. I remember the worst day of my life, the day of fear when I forgot how to breathe...”

A tall girl in a black dress and light-grey headscarf does not raise her eyes from the text as she recites. Her face is hidden under a mask – a handy accessory that protects from both dust and unwanted attention. The girl's voice, feeble and trembling at first, becomes more confident with every sentence.

Mr. Adib, his eyes closed, nods with the air of a music lover listening to a beautiful melody.

“Very good, Parwana. Wonderful. You may sit. Who is going to be the next brave one?”

The house of the alive

There are 13 girls in the classroom, between 16 and 20 years old. Some of them wear full hijab, and others have head scarfs barely perched on the back of their heads. Some are dressed in grey or dark blue, others in pink and floral prints; some of them keep quiet, and some raise their hands to ask questions. Slim or chubby, smiling or thoughtful, curious or shy, these girls have one feature in common: They were at school on the fateful day of May 8, 2021, and remember the attack. They all joined the course to overcome their fears and gain respite from the new stressful reality. Despite the favorable changes Mr. Adib has witnessed in the girls' mental state, as well as in their writing skills and self-esteem, over the past seven months, there is a lot of healing ahead.

“I was scared to go out after that day. And our teachers were scared; after the blast, we only had three of them for 12 classes,” Farah, 17, says.

“And now we are scared, too. If the Talibs find us here, I am sure they will punish us,” Mariam, 16, says. “But we have the right to study and do not want to give up so easily.”

“Once a Talib stopped me on my way here,” Parwana, 18, recalls angrily. “He was rude. He asked me if I was not ashamed of myself because I was going to the educational center that offers classes for men. How stupid is this? The boys who come here to learn English are young kids, not older than 10 or 11 years old!”

Five students of Mr. Adib are thinking about a career in journalism; the rest agree that writing skills are vital. The world must know the truth about Afghanistan, and there must be people who can convey this truth.

“Every day is precious, be it sad or happy, and we must remember them all,” Mr. Adib remarks philosophically. “And it is easier to remember if we take notes. Remember that novel by Dostoevsky, ‘The House of the Dead’? Here is the house of the alive, though.”

After the lesson, chatting girls depart the educational center in small groups. Mr. Adib walks them to the door, then gets on his scooter parked outside. Cutting a neat and elegant figure in the chaotic streets of Kabul, he rides away, leaving a Taliban checkpoint behind.

*All names changed to conceal the characters’ identity.