The West wants to disarm the 'powder keg' of Europe, but it risks igniting it

The events throughout late July in the Balkans – alarms sounding at the administrative border between Serbia and Kosovo, locals hastily erecting barricades, gunshots, forces redeploying, calls for peace from the Serbian president and NATO’s vow to intervene should the situation escalate – have led many to believe Europe is on the brink of another war.

Yet diplomatic efforts were somewhat successful: Pristina agreed to postpone for a month its decision – the source of the tension in the first place – to bar holders of Serbian documents and license plates from entering Kosovo. This has given diplomats enough time to convince the sides to make mutual concessions and work out a compromise. The resolution will most likely only delay an escalation that has been looming over the region for several decades already. Despite being smaller than Connecticut in the US or Thuringia in Germany, these 11 square kilometers of historic Kosovo lands are still in the middle of a crisis that can affect the whole world.

Russian author and historian Evgeny Norin explains where Kosovo went wrong and why it remains a volatile problem

Why Kosovo is Serbia

Just a day before the agreement was struck between Serbia and Kosovo, US Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs Gabriel Escobar made an infuriating statement, “It’s time to forget the narrative ‘Kosovo is Serbia’ and move to the one that says ‘Kosovo and Serbia are actually Europe.’”

The US diplomat offered Serbs a brighter future in exchange for giving up their historic lands. His words, however, sparked protest among the Serbian public and politicians.

“The line between terrorists and freedom fighters is very thin for them. This is US policy. What can you expect from Mr. Escobar? Why do we keep pretending we don’t know what it is about?” said an outraged Serbian president, Alexandar Vucic, in an address to the nation.

Escobar’s rhetoric didn’t go unnoticed in Russia either. Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova reminded her American colleague that “UN Security Council Resolution 1244 <…> is still the legal framework for the Kosovo settlement, clearly reaffirming the territorial integrity of Serbia.”

There are two sides to this story, but history definitely favors the Serbian and Russian perspectives.

Kosovo is located in the south-west of Serbia, near the Albanian border. In the 12th century, it became part of the nascent Serbian state, gaining prominence during the Middle Ages. The head of the Serbian Orthodox Church resided in Kosovo’s Pec. Kosovo also played an important role in the building of the Serbian nation. The Battle of Kosovo, when the Turkish army fought the Serbs and won, became one of the bloodiest battles in Serbia’s history and a symbol of heroic defeat. A large portion of Serbian poetry is dedicated to those events.

Kosovo’s role as the cradle of Serbia’s nation and culture is colossal.

Ottoman legacy

During the Middle Ages, the Balkan region was mostly controlled by the Ottoman Empire, and in fact the origins of the Kosovo conflict date back to that era. Constantinople actively tried to draw the distant regions of the empire into the Turkish fold, thus transforming the ethnic fabric of the Balkans.

Kosovo was populated by Serbs and Albanians, whose settlements were more to the west, near the sea. Under Ottoman rule, the Albanians quickly adopted Islam and began to absorb Turkish culture, becoming the Sultan’s base in the Balkans. The Albanians and Turks relocated to Kosovo, while some Serbs moved closer to their fellow Christians across the Danube.

By the mid-19th century, when the Balkans entered another turbulent era, the Albanian and Serbian communities in Kosovo were about the same size. But the turmoil of the 19th and especially the 20th centuries radically changed the balance.

Echo of World War Two

It should be noted that borders separating the different ethnicities in the Balkans were almost impossible to draw. The map had the appearance of leopard skin: Serbs, Muslim Serbs (who eventually became a separate group – Bosniaks), Croatians, Montenegrins, and Albanians.

When the Ottoman Empire first lost control of the Balkans, Kosovo became part of Serbia and later of Yugoslavia. But when the region was occupied by Germany and Italy in the 20thcentury, the powder keg exploded once again. The occupying regime in Kosovo was harsh, running Serbs out of the region and killing many. Kosovo was given to Albania, while the reign of terror forced Serbs to flee.

While Yugoslavia was restored in 1945, Kosovo’s residents became hostages of Josip Tito’s political vision. Tito blocked the return of Serbian refugees to Kosovo, instead wanting to use the province as a ‘bridge’ to influence Albania. He also made some new Serbian territories part of Kosovo. However, his hopes were not realized – the bridge to Albania was never built. Instead, Kosovo was heavily influenced by Tirana, and Albanians now comprised the majority of its population.

Tito’s miscalculations

In fact, the ‘national portrait’ of Kosovo changed almost completely. The process started under Turkey’s rule and was ‘semi-natural’ in essence, and continued through the time of the Nazis and Tito, becoming almost completely artificial. As a result, Serbs were reduced to a minority in a region which they continued to consider their sanctuary. Estimates of Kosovo’s ethnic community profile before the breakup of Yugoslavia differ, but it’s safe to say that Serbs made up about 20% of the province’s population. Apart from Albanians, who accounted for 65-75% of Kosovo’s population, according to various estimates, the territory was also inhabited by Turks and Roma.

It was at this time that Albanian nationalist organizations emerged from the shadows andhave been active in the region ever since.

Although the breakup of Yugoslavia is traditionally believed to have started in the late 1980s, problems actually began in Kosovo earlier in the decade. Tito had managed to suppress the separatist movement with an iron fist. However, throughout the 1980s pressure on the Serbian population mounted at the hands of Albanians, who dominated the region’s ethnic landscape. There were many cases of routine community sabotage, minor crime, as well as incidents of assault and battery, arson and threats.

The Yugoslav elite tried to tackle the Kosovo problems. One of the greatest challenges thatinfluenced every development in the secluded province was overall poverty and pooreducation. Belgrade tried to address this by implementing educational programs. Under Tito, a university was set up in Pristina, Kosovo’s capital, where instruction was provided in Albanian. But what Yugoslavia ended up achieving by this was the rise of a nationalist elite composed of Albanian intellectuals.

Kosovo’s ambitions

As a result, by the early 1990s, Kosovo was ripe for a breakaway – including military secession. The prevailing Albanian population dreamed of the province separating from Yugoslavia, and this sentiment was actively encouraged by neighboring Albania. During Tito’s rule, it managed to form its own intellectual stratum that could provide a solid ideological foundation for Kosovo’s breakaway ambitions. Poverty and low living standards in Kosovo provided a constant flow of recruits with nothing to lose into Albanian militias.

In 1991, an independence referendum took place in Kosovo, followed by presidential elections. Yugoslavia (by then only Serbia and Montenegro remained) refused to recognize the results. However, by that time local politicians had moved into the foreground in Kosovo.

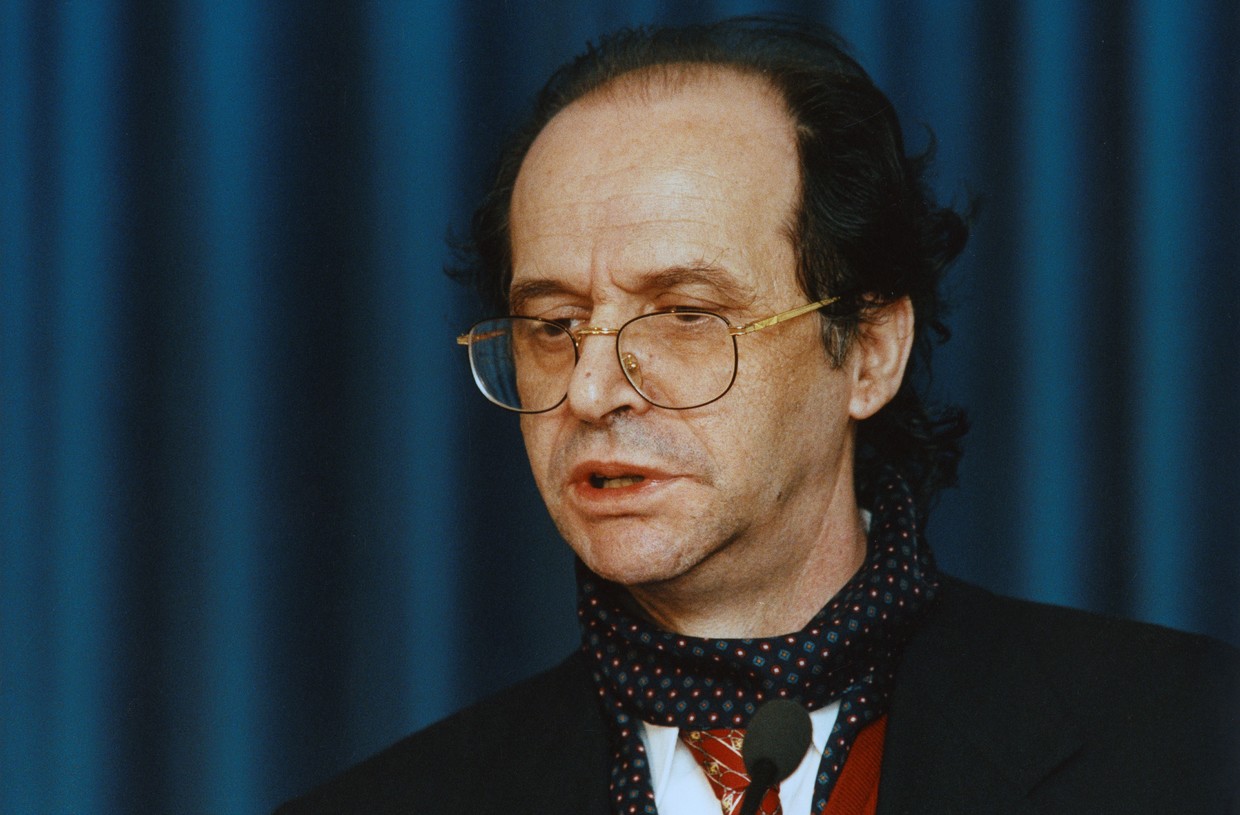

Ibrahim Rugova emerged on the Kosovo political scene and remained a key figure in the years to come. A dedicated opposition member, editor, and doctor of literature who had graduated from the University of Pristina, he represented the group of Albanian humanitarian intellectuals educated by Yugoslavs in an effort they did not expect would boomerang. Rugova was part of a moderate faction and a proponent of political struggle. But then in the mid-1990s, a militant group formed within the Albanian separatist movement – the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA). The plans of Kosovo’s Albanians went far beyond their homeland and extended to another ex-Yugoslavian republic populated by Albanians: North Macedonia.

Atrocities of war

The KLA largely engaged in guerilla warfare and terrorism. Belgrade’s control over Kosovo was deteriorating, and its attempts to suppress the insurgency were met with intense resistance, which turned into a bloody protracted war. Historians mostly agree that the war began in 1998, although major acts of violence were also committed in the preceding years.

Coverage of the conflict by the Western mass media was consistently skewed. While Serbian forces did in fact carry out some brutal attacks, the Serbian population was being increasingly terrorized. The truth is that both sides were guilty of ethnic killings of both combatants and civilians. Many ethnic Albanians fled from Kosovo to Albania – only to find the KLA propaganda arm recruiting them as fighters.

The 1999 Racak massacre was one of the darkest pages in the conflict’s history. In retaliation for the killing of a Serbian policeman in an armed ambush, Serbian forces raided the village of Racak. The raid resulted in the deaths of 45 Albanian civilians. While Albanians insisted that only nine were combatants, the Serbs maintained that all casualties were members of the rebel forces and were killed in combat. The issue remains controversial to this day. Even though the Racak massacre was neither the bloodiest nor most indisputable act of aggression during the war, it became the turning point in the Kosovo conflict. What followed was the NATO bombing of Yugoslavia.

Enter NATO

Negotiations around the Rambouillet Accords had hit a dead end. The Serbs were ready to sign off on a ceasefire and autonomy for Kosovo but were not ready to agree to an international military presence in the province. NATO had accused Belgrade of torpedoing the peace deal while, in fact, no attempt was made to try to meet Yugoslavia half-way. Instead, Belgrade was only presented with a series of ultimatums. The mass media portrayed Serbia as the ultimate villain, while NATO proceeded to assemble an air force.

March 24, 1999 saw the US-led NATO force begin its operation against Yugoslavia. The chosen strategy was to win by air power alone. NATO’s dominance in the air was indisputable, and Serbian air defense systems were taken out very quickly.

While the Serbs did not suffer any extensive loss of manpower, except in the air force and air defenses, NATO’s strikes succeeded in ruining Yugoslavia’s extensive civilian infrastructure, including airports, bridges, factories and power plants. Civilian casualties from the air strikes were also quite significant and even included the deaths of some Albanian refugees.

The KLA’s combat activity wasn’t very successful. It lost a number of battles on the ground despite NATO’s support from the air, but for Serbia to continue fighting while losing critical infrastructure every day was entirely pointless. On June 10, 1999, Yugoslav President Milosevic capitulated, agreeing to all of NATO’s requirements. By that time, according to different estimates, between 500 and 5,700 people had been killed by the air strikes. International troops entered Kosovo.

Disappointing aftermath

Violence continued in Kosovo, with more than 1,700 local residents killed or reported missing in the following months, as many of the Serbs who had remained in the province fled. All in all, hundreds of thousands of people – up to 350,000 according to some estimates – had to leave Kosovo, mostly Serbs but a significant Roma population too. The NATO contingent failed to stop the ethnic cleansing, meaning the remaining Serbian population is now clustered in only a handful of districts.

Several years of negotiations on the status of Kosovo yielded no concrete results. In 2008, Kosovo declared independence, which was acknowledged by a large proportion of theinternational community, but not all of it.

The Kosovo issue remains a painful one for Serbia, especially given the fact that the country is still home to several hundred thousand Kosovan refugees. Ethnically motivated clashes still occur in Kosovo on a regular basis. The region has been in turmoil for a long time, and simply bombing Serbia was not a solution to its problems.

Two enemies for the price of one

The finale of the Kosovo drama (or what might have been considered as such in the late 1990s and early 2000s) had important implications for public opinion in Russia. As far as one can judge, the West cares little about Russia’s changing attitudes to westernization. And yet 1999 was a turning point for the Russian people in many respects. For a long time, Russians had entertained profoundly idealistic views of the collective West (Europe and the US), but the events in Kosovo came as a sobering shock to those with West-leaning sympathies.

Even those who had no particular affinity for the Serbs saw the obvious – the bias of the Western community that effectively greenlighted ethnic cleansing and launched a bombing campaign against a European state, which resulted in heavy losses among Yugoslav civilians and significant destruction of the country’s infrastructure. It was not just about the Russians’ traditional sympathy for the Serbs, but that in the ‘Serbia vs. West’ standoff, Russians naturally sided with the underdog, which was even more understandable given the smoldering conflicts in Russia’s Caucasus, where it was being confronted by Islamic terrorist groups.

The moral legitimacy of pro-Western ideology in Russia was severely undermined as a result. Against the backdrop of the devastation in Belgrade, Western leaders’ claims about humanistic ideals and freedom were – and still are – perceived as nothing more than blatant hypocrisy and cover in service of their own political and economic interests. Naive idealistic sentiments, so prevalent in Russian society until then, were dealt a crushing blow and began to disintegrate, a process that kept gathering momentum and resulted in full-blown antagonism two decades later.