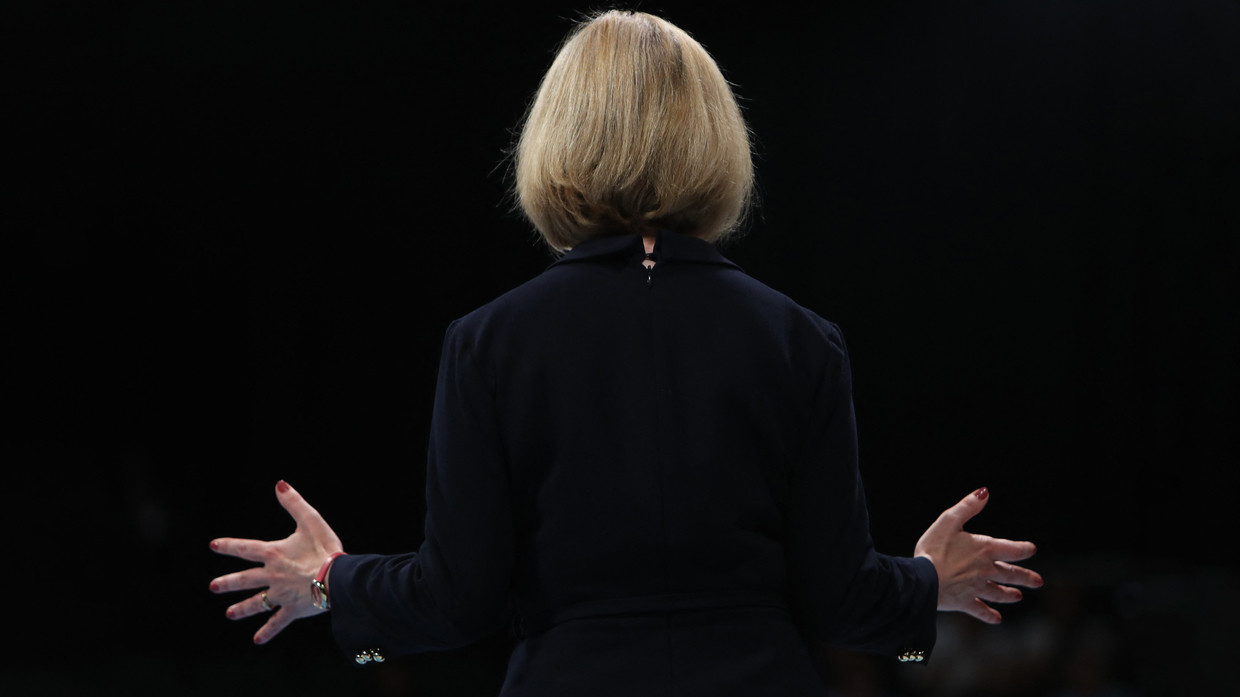

Even fervent believers in the stability of Western democracies must surely have had their faith shaken last week by the extraordinary economic and political crises created by the newly-minted UK prime minister, Liz Truss.

In the week after the prime minister’s hand-picked chancellor, Kwasi Kwarteng, handed down a ‘mini-budget’ on September 23, the English pound crashed; the government bond market took a dive; interest and mortgage rates rose; some mortgage markets shut down; the Bank of England staged a highly unusual fiscal intervention to prevent the collapse of major pension funds; and the IMF criticized Truss in a manner usually reserved for the leaders of debt-ridden banana republics.

The global importance of these events and the ongoing economic and political disruption that they will inevitably cause should not be underestimated. Political commentator Alastair Campbell, formerly Tony Blair’s chief of staff, accurately described last week as “the week that everything changed.”

What led to the UK economic crisis?

Quite simply, the fact that the Truss mini-budget provided for billions of pounds worth of unfunded and uncosted tax cuts – including, most provocatively, a cut in the 45% top level income tax rate – caused the financial markets to register a serious vote of no confidence in the Truss government, with all the attendant consequences that followed.

Incidentally, the events of last week show where real power ultimately lies in the West – and it is definitely not with politicians.

Truss’s mini-budget is, of course, a product of the crude neo-liberal economic ideology that she so fanatically believes in, and which proved decisive in attracting the 80,000 or so Thatcher-worshipping members of the Tory party that anointed Truss prime minister only a few weeks ago.

Faced with an economic disaster entirely of her own making – one of her first acts as prime minister was to sack the head of the Treasury – Truss simply doubled down, and retreated petulantly to her Downing Street bunker.

She did emerge briefly late last week to do a round of disastrous radio interviews with regional BBC stations – in which Truss continued to robotically tout the benefits of ‘trickle-down economics’, and (unsuccessfully) tried to blame the economic crisis entirely on Russian President Vladimir Putin and the conflict in Ukraine.

Not surprisingly, the vast majority of commentators in the UK – irrespective of their political affiliations – have been strongly critical of the Truss mini-budget and the prime minister herself. Even Daily Telegraph columnist Ambrose Evans-Pritchard accused Truss of having “embarked on a course of sheer madness.”

Truss’ intransigence, however, means that the current economic crisis can only intensify – with predictions of a housing market crash as the next most likely catastrophe to engulf the UK.

The ongoing UK rail strike ramped up last week, and further economic convulsions will no doubt occur in late November when Truss and Kwarteng have condescended to outline the vast array of spending cuts that will fund the mini-budget tax cuts.

Truss’ attempt to remedy the deep-seated problems that bedevil the UK economy (including decades of wage stagnation, ongoing working class and middle-class impoverishment, the ever-widening gap between rich and poor, dramatically rising energy and food prices, and the crisis in housing affordability) by applying neo-liberal economic policies has failed spectacularly.

This is an ominous sign for Western democracies generally, because significant segments of the global elites that rule them remain firm adherents of the greed-based, crude neo-liberal economic theories that Truss and Kwarteng so rigidly embrace. These elites do not believe in noblesse oblige and are committed to overturning the social democratic consensus that prevailed in the UK from Atlee until the election of Thatcher.

Irrespective of that, what should be of most concern to intelligent observers is the demonstrable fragility of an economic system that descends into severe crisis within a few days of a mini-budget – no matter how misguided and foolish – being handed down.

Unfortunately, the political crisis created by Truss is perhaps even more serious than the economic crisis that she has unthinkingly engendered.

The immediate political dilemma is the one now confronting the Tory party.

Such has been the intensity of the adverse reaction to the events of the past week that it is already clear that the Conservatives cannot possibly win the next election, and that Truss cannot realistically remain prime minister for long.

A poll taken at the end of last week shows that the Labour Party now leads the Tories by an astounding 33 percentage points – up from 17 points just prior to the handing down of the mini-budget.

In one week, Truss has done what no Labour leader has been able to do in decades – namely, give Labour a seemingly unassailable lead in the polls. Truss also appears to have brought about a significant rapprochement between Keir Starmer and the trade union leadership, and invigorated the party generally.

As for Truss herself, as Alastair Campbell said last week “She’s dead… she’s toast.”

Under existing Tory party rules, however, Truss cannot be challenged for 12 months – and, even if she could be, a new leader would have to be elected by the same lengthy and deeply flawed process that so recently threw up Truss as party leader.

The only way out of this dire situation would be for Truss to resign, and be replaced without the need for a leadership contest. But Truss shows absolutely no signs of relinquishing her position, and even if she did, the ensuing divisions within the Tory party would surely make a leadership contest inevitable.

Of course, yet another change of Tory leader would render the party even more unelectable than it is now.

Under the circumstances, there is, I think, a very real possibility that the Tory party will split, with the Truss neo-liberal wing hiving off, leaving a Cameronesque rump behind. A new right-wing populist party may emerge from such a split. If so, this would mirror what has occurred within conservative parties in some other Western democracies in recent years.

But whatever happens, there can be no doubt that the hapless Truss will have the privilege of having presided over the demise, in whatever precise form that it takes, of the contemporary Tory party.

The Tory party conference that began in Birmingham on Sunday – it has understandably been boycotted by a large number of angry and disgruntled backbenchers – promises to be a very interesting event indeed. It started off badly for Truss with prominent Tory MP Michael Gove condemning her mini-budget as being “not Conservative” and hinting that he and other Tory MPs might vote against the Truss tax cuts in Parliament. This caused Truss to panic and reverse the upper income tax rate cut, which only further damaged her credibility.

The political crisis that is currently intensifying in the UK has highlighted a number of inherent defects within the political system that currently operates in most Western democracies. They include the following:

First, it is clear that any political system that allows a genuine prime minister like Boris Johnson to be deposed for a few minor misdemeanors, and replaced by someone as demonstrably incompetent as Liz Truss, is irretrievably broken.

Second, any political system that encourages and permits a rapid and regular turnover of leaders – sadly a defining characteristic of politics in the West these days – can only perpetuate ongoing general political instability.

Third, party leaders should be elected by members of Parliament, not the party membership. Election by members debases the quality of candidates and policies alike, and leads to ongoing instability and destabilization in circumstances, as is often the case, where the elected leader does not command the support of a majority of parliamentarians. This was the case under Jeremy Corbyn’s recent leadership of the Labour Party, and it is now certainly the case with Truss.

Fourth, politics needs to attract a far better quality of politician than it currently does.

Fifth, if the Conservative Party does split, this may lead to a particularly dangerous consequence, namely the formation of a new right-wing populist party of the kind that has recently emerged in Germany, Sweden, Italy, and elsewhere in the West. Such a development can only destabilize politics further, as it has done in each of those countries.

Whether it is possible to achieve any of the abovementioned reforms or prevent the emergence of a populist party in the UK are, I think, very much open questions.

It has always been obvious that Truss is a fourth-rate politician. She is completely lacking in real intelligence, empathy with voters, and political judgment. But Truss is no worse than the average politician who these days regularly attains high office in Western democracies.

I doubt that Truss will survive as prime minister for much longer, and she would seem to have no future beyond that in politics.

Perhaps her most significant political achievement is to have dramatically highlighted, in the short space of a week, the inherent and fundamental instability that underpins the economic and political systems that currently hold sway in the West.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.