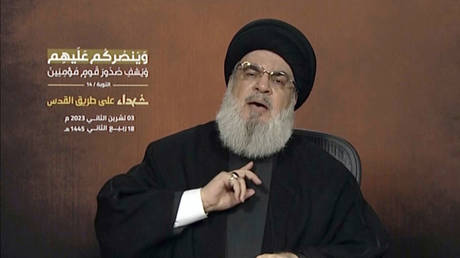

The leader of Hezbollah, Hassan Nasrallah, delivered a much-anticipated speech outlining his organization’s approach to the ongoing conflict between Hamas and Israel in Gaza. At the same time Nasrallah was speaking, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken delivered some remarks of his own and took questions from the press about the Gaza conflict and the resulting humanitarian crisis that has gripped the Palestinians there.

In the leadup to Nasrallah’s speech, Hezbollah had released several videos suggesting that something momentous was going to come out of his presentation. Many observers, angered by the ongoing slaughter of innocent Palestinian civilians – many of them children – through the indiscriminate bombing of Gaza by the Israeli Air Force, believed that this was the moment when Nasrallah would unleash the might of the Hezbollah resistance, exacting revenge on an Israeli nation that had operated outside the framework of international law for far too long.

Other observers believed that Nasrallah would fail to rise to the occasion and would offer the Palestinian people, whose cause he claimed to champion, nothing more than empty platitudes when they needed a second front.

Blinken’s remarks, on the other hand, were not prepared in advance, but rather a byproduct of an American diplomatic intervention designed to preempt any potential Hezbollah action. The fact that Blinken and Nasrallah delivered their remarks simultaneously was no accident – Blinken was clearly seeking to distract from the Hezbollah leader’s ‘moment’.

But the simultaneous messaging signaled something else as well – that the message being imparted by each of the parties was not contingent upon the content of the other, but rather set in stone prior to Nasrallah’s presentation (indeed, the fact that Nasrallah did not deliver a live address, but rather had pre-recorded his speech, underscores the reality that what was happening was carefully constructed theater.)

On the surface, the tone and content of these competing presentations appear to point to mutually incompatible goals. Nasrallah said Hezbollah’s objectives were to “stop the aggression” against Gaza and assure that Hamas “achieves victory” against Israel, and that to help this, his troops had tied up a part of Israeli forces in skirmishes at the Lebanese border. Blinken, for his part, warned both Hezbollah and Iran against “taking advantage of the situation” and opening a second front.

If you look deeper, though, the fact is both Nasrallah and Blinken were actively seeking to avoid an escalation of the Hamas-Israeli conflict, not by stepping back from their respective strongly held positions, but rather by implementing a carefully managed process of escalation management, where each side created the opportunity for the passions generated by the Gaza conflict to find outlets sufficient to relieve the pressure, while simultaneously avoiding any precipitous escalation of violence or geographic expansion of the zone of conflict.

In short, both the US and Hezbollah were, and are, implementing a model of conflict management known as the ‘escalation ladder’. And while this reality might prove frustrating for those on either side of this conflict who seek a decisive, one-sided victory, it is the only responsible path that can be taken to avoid turning a local conflict into a regional war that could have global ramifications.

The escalation ladder process focuses on how the parties involved escalate and de-escalate against competitors, measuring these actions against the different levels of escalation, which equate to the ‘steps’ on the ‘ladder’ used to visualize the model. By assessing the possible upward or downward trajectory of escalation at each level, based upon the actions of each party and their outcomes, the model helps participants to predict plausible outcomes and, as such, plot future scenarios. The most popular expression of the escalation ladder is what is known as ‘linear escalation’, where a sequential line of actions is plotted from lowest to highest, and the relationship between two competing powers assessed accordingly.

Linear escalation as a model works if there are only two participants to the crisis in question. The problem with the ongoing Gaza conflict is that there are many parties to the conflict, all of which have differing goals and objectives. As such, the escalation model that is most applicable to this scenario is what is known as horizontal escalation, where within a given escalation vector, differing participants can be segregated based upon their respective goals and objectives, allowing a sub-set of comparative escalatory calculations to take place, which in turn can be subjected to factors that influence their specific escalation, de-escalation, and maintenance issues separate from other parallel escalation management trajectories.

By way of example, one can speak of a ‘horizontal escalation’ model, where a US/Israeli track is paired off against a Hamas/Hezbollah track. However, the US/Israeli track is also paired off against itself, since the US and Israel are at odds over ceasefire options, the provision of humanitarian air, and specific military tactics. The same applies to Hamas/Hezbollah, where the Palestinian-specific goals of Hamas may clash with the regional aspirations of Hezbollah. Moreover, the specific actions of the US and Israel, when competing, can impact the Hamas and Hezbollah escalation calculations differently, causing these two tracks to lose their equilibrium by having one party escalate when the other may be seeking either maintenance and/or de-escalation.

The horizontal escalation model becomes even more complex when other tracks, such as the United Nations, the international community, Iran, Yemen, and the Iraqi and Syrian Shia militias become involved. When seen in this light, the horizontal escalation model becomes horribly complicated, requiring all parties to be cognizant about the competing interests of everyone involved, and develop a sound understanding of the intricacies associated with every facet of the cause-effect relationships involved.

When deciphering the presentations given by both Blinken and Nasrallah, the casual observer might be compelled to be highly critical of the less-than decisive content provided. But a careful parsing of the language used by both men shows that each, in his own way, is cognizant of the complexity of the issues at play, and the absolute need to manage the pressures generated by the emotions of all parties involved so that a crisis that could easily expand into a regional war remains localized.

However, one cannot escape the reality that, at the end of the day, there cannot be a solution that is satisfactory to all parties. Israel seeks the destruction of Hamas as a military and political entity. Hamas seeks a Palestinian homeland built in its image. These two visions of victory are mutually incompatible. Both parties will seek to manipulate the escalation ladder in a way that best promotes their respective desired outcome. The key to the other parties is how to prevent this inherent incompatibility from spinning out of control, and to manage defeat as well as victory.

It is this aspect of the escalation management process where Hamas has the advantage. As Nasrallah repeatedly noted in his presentation, the most important aspect of the anti-Israeli resistance is its ability to persevere. Israel finds itself in an increasingly untenable situation, where the political and military methodologies undertaken are increasingly rejected by its supporters. The friction between the US and Israeli positions was evident in Blinken’s address. This friction will only increase if the conflict between Israel and Hamas is maintained on its current trajectory. The only chance Israel has to break this paradigm is if the conflict escalates, forcing the US to reevaluate its conflict resolution model with larger geopolitical concerns, such as a war with Iran. Blinken has made it clear that the Biden administration is not seeking such an outcome.

Neither is Hassan Nasrallah.

It is in this light that one must examine the totality of Nasrallah’s speech, and the complexity of his argument. There is not a single facet of the Israeli-Hamas conflict he left unexamined. Moreover, he not only discussed each of these matters in isolation, but also in respect to how they relate overall. Nasrallah’s speech was the embodiment of how to manage a complex horizontal escalation model and achieve a desired outcome.

Let there be no doubt – Hamas is on the trajectory toward victory, though not the kind of victory a casual observer might imagine as its end goal. When the definitive history of the Hamas-Israeli conflict is finally written, rest assured that the speech given by Hassan Nasrallah will be recorded as one of the critical moments in shaping the conflict so that it avoided exploding into a wider war, and instead allowing the various parties to focus on the more limited, although admittedly complex, issues relating to the core matters as defined by Hamas – a prisoner exchange, freedom of religion at the Al Aqsa Mosque, and Palestinian statehood. These limited objectives, and not the destruction of Israel, are the likely outcomes of this conflict. And for that we can all thank Hassan Nasrallah, a man who knows how to effectively manage the complexities of the horizontal escalation model.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.