When unsure whether you suffer from a virus or bacteria, just take a snapshot of your immune system. So say American researchers, who are developing a blood test that could save millions, prevent pandemics and cut back on wrongly prescribed medication.

The crux of the problem is that symptoms are not enough for a diagnosis. The doctor’s only weapon is to prescribe a test which detects a certain pathogen. Presently, the test is usually chosen based on common sense, e.g. “is there currently a flu epidemic?” And if the usual suspects do not show up, additional testing – which may take days – is necessary.

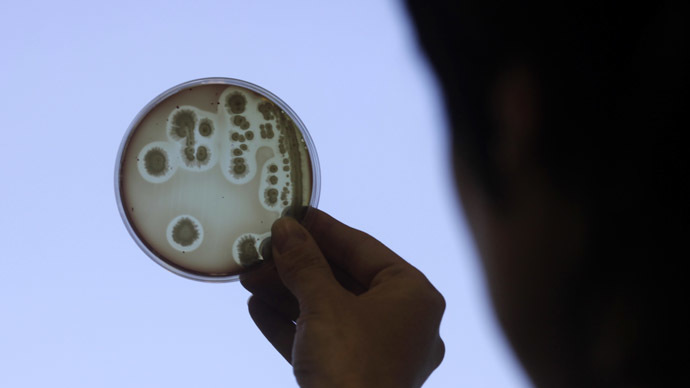

Correct identification of ‘signatures’ in every affliction is in this case necessary. Here is the solution the Duke researchers came up with: photographing gene activity at the onset of infection. Before a person even feels the first symptoms of an illness, sets of genes are dispatched by the organism to battle it. But a viral infection is fought with a different set of genes than a bacterial one, for instance. This also leads to differing RNA and protein formations, otherwise known as a genetic fingerprint.

With this information doctors will be able to identify and diagnose diseases correctly and in time, prevent pandemics, possibly recognize infections at the incubation stage, as well as dramatically cut back on erroneous prescriptions.

For instance, knowing that an infection is not a virus automatically rules out antibiotics as treatment. And it is becoming common knowledge that germs mutate and become resistant to antibiotics. Drug-resistant germs are the cause of over 23,000 deaths annually. And when dangerous viruses, such as the new MERS, begin to spread rapidly, a revolutionary technique like genetic fingerprinting could be a solution in the future.

Dr. Geoffrey Ginsburg, who is the head of genomic medicine at Duke University, told the Associated Press that the “viral signature could be quite powerful, and may be a game-changer.” On Wednesday, his team got results back from a 102-person study that proves the new test works.

Dr. Aimee Zaas, who is lead researcher at Duke, explains how the new test works. The Duke team recognized 30 genes that switch on during a viral attack. This led the scientists to the idea of taking a still of their activity at the time of infection or “what those genes are doing at the moment in time that it’s captured.”

Concrete evidence of a viral signature was first spotted in people who volunteered to be infected with differing strains of flu for the experiment. For a more real comparison, researchers then took blood samples from previously sick walk-in patients who were diagnosed much later.

The results of the genome test proved remarkably accurate: in 89 percent of the cases a viral signature showed itself to be distinct from a bacterial one, according to Zaas’ Wednesday report in the Science Translational Medicine journal. Her results took about 12 hours. Now, everyone’s hope is to speed that up to being almost instant, the way in-office tests work.

As Dr. Octavio Ramilo of Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus (Ohio) pointed out, children are usually the first victims of slow diagnosis, because “in the beginning [virus and bacteria] look completely alike.” Therefore, he agrees that this is groundbreaking and predicts that the Duke team will come up with a working, widely used procedure within five years.

Ramilo, whose research runs parallel to the Duke discoveries, has decided to take their finds a step further. One very pressing problem is diagnosing and saving infants with serious bacterial infections in time. To do this, Ramilo has taken a sample of 22 pediatric emergency rooms to attempt to extrapolate a fraction of high-risk babies that need an extensive set of tests. Because this is currently the default procedure for any infant with fever, the success of genetic fingerprinting could drastically cut waiting time.