Memory, not history: 70 years on, Crimea's Kerch celebrates liberation from Nazis

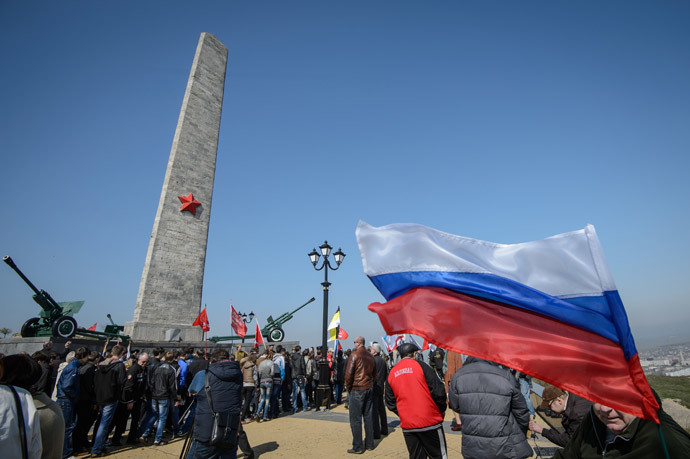

It's been a solemn day in Crimean city of Kerch as veterans and the locals pay tribute to Soviet soldiers and civilians who suffered enormous losses in the bloody WWII fight with Nazi occupants – a memory cherished in the region to this day.

Reclaiming Kerch: A hard-won WWII battle for Crimean Hero City (PHOTOS)

Commemoration ceremonies have been held April 10 and 11. People laid flowers at the monuments to Soviet soldiers who died in their thousands on tiny strips of coastal land and in catacombs of the Adzhimushkay quarry while fighting the Nazi invaders in 1941-44.

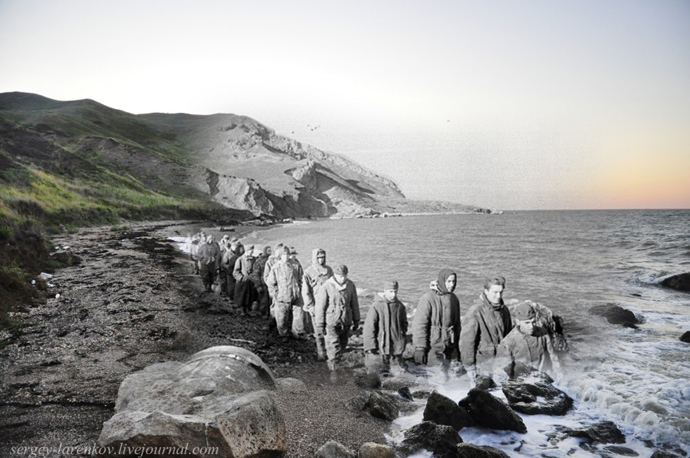

One such memorial spot lies in what used to be a small village of Eltigen, where Soviet troops carried out a major landing operation. Known as the Kerch–Eltigen Operation, the November 1943 amphibious landing was met with a hail of fire from Nazi German reinforcements. The landing spot at Eltigen was referred to as “burning land” by the battle’s participants. Soviet troops were eventually forced out of Eltigen but managed to hold onto a beachhead west of Kerch, which in April 1944 served as a crucial launch pad for Crimea’s liberation.

Memories of ruthless battles survive in the tales of veterans, who are particularly revered in Kerch.

Marine trooper: ‘I still don’t know how we made it’

For the decorated Kerch veteran and guerilla fighter Aleksandr Lubentsov, an armored attack by the Nazis is still a haunting memory. Lubentsov describes in detail the episode when the Soviet troops holding Kerch peninsula were bombed into the ground by endless Luftwaffe raids and overrun by German tanks in May 1942. At that time, the Red Army suffered a crushing defeat, losing a total of more than 160,000 soldiers, either captured or killed.

“In the morning we saw German tanks coming in a V formation from the hill. There was an awful lot of them… Our artillery opened fire but that didn’t even slow them down. Some tanks were hit, but the others immediately turned to the left and outflanked us… German bombers and dive bombers hovered over us. It was a nightmare, literally a carrousel – some of them coming, some flying away. They didn’t let us raise our heads for the whole day… The day had been quiet and sunny. But now we saw the sun as if through smoked glass. We could not see anything because of the smoke,” Lubentsov told I Remember website.

“Everything was burning. German motorized infantry that followed the tanks fired machine-guns at us, we fired back from automatic rifles, threw Molotov cocktails at the enemy’s armored vehicles. The people were burning, the tanks were burning. But we managed to break out of the encirclement,” he says.

While he witnessed whole battalions die in fires and many of the captured Soviet soldiers executed by the Nazis, Lubentsov managed to stay alive with the help of the locals. After a string of hopeless battles, in which only he and his Ukrainian pal remained alive, the two had to “mix with locals,” who hid them despite a clear threat of execution.

“We left at night. German soldiers were guarding every meter of Kerch… I still don’t understand how we made it through,” Lubentsov says.

However, the Nazis were determined to clean out the hiding Soviet troops and actively used ethnic differences to lure them into a trap.

“The Germans started a rumor, trying to divide nationalities. They said: ‘Ukrainians, do not hide, come out and we will give you a passport and send you to your homeland,’” Lubentsov recalls.

His Ukrainian friend decided to apply, but instead of getting a passport he was “put behind the wire,” and then sent into a concentration camp elsewhere. Lubentsov never learned what happened to the man, but says that “of those captured in 1941-42, few survived.”

The Russian marine then went into hiding and became a “partisan,” often leading guerilla operations against the Nazis. The guerilla fighters of Kerch played an important role in the subsequent liberation of the peninsula, ambushing retreating German-Romanian troops and capturing whole villages and towns. The Nazis left a gruesome trail, in one instance killing several hundreds of unarmed civilians, including women and children, before setting off from Stary Krym. Lubentsov witnessed the aftermath of the carnage.

Many Crimea veterans remember how some of the Crimean Tatars were turned into Nazi agents, ratting on the Soviet soldiers in hiding and carrying out executions. However, Lubentsov, who saw the Stalin-ordered Crimean Tatar deportation with his own eyes, says the move to deport the whole ethnic group was completely unjust. Those Tatars who collaborated with the Nazis retreated with the German troops, while most of those who remained were “innocent,” he says.

“Of course, that was a tragedy for the [Crimean Tatar] nation. You cannot judge everyone by the actions of some. We in fact had guerilla fighters from the Crimean Tatars, including some of our commanders.”

Adzhimushkay defender: ‘They gassed us from 10am till night’

The so-called partisans leading the guerilla fight from the woods and catacombs of Kerch were the Nazi’s most hated foes. The invisible resistance of Adzhimushkay quarry defenders, where up to 15,000 cut off Soviet soldiers and civilians sheltered in May 1942, could not be quelled for months despite the occupation.

A fact that the Germans have never admitted and that the Soviet leadership for years concealed among the other facts about the heavy loss of life was the use of toxic gas by the Nazi troops against the people hiding in Kerch catacombs.

Of the 13,000-15,000 people who hid in the underground passages, it is believed that only 48 people came out alive in the end.

One of the few surviving Adzhimushkay defenders, Mikhail Radchenko, recalls that the gas attacks started after the Nazis failed to force the people out of the catacombs by shelling and bombing and apparently in response to daring night raids.

“The Germans would start at 10 in the morning and pumped the gas till nighttime. We used to immediately lie down on the ground, trying to breath the underground moisture,” Radchenko is cited by Rossiya 1 channel.

According to the veteran, thousands died in those days of gas attacks.

While May 26 has been celebrated in Kerch as Partisan’s Day, there is another, tragic date of November 29, which the locals also mark. The Jewish community of Kerch annually gathers at the site of Bagerovsky Ditch massacre, in which some 7,000 people were executed by the Nazis in November and December 1941. The shocking scenes of hundreds of hastily buried bodies of men, women and children was the first sight of the Nazi German holocaust for the Soviet troops, who came across the ditch in early 1942.

Medic, scout, liberator of Kerch and Europe: Katyusha Mikhailova

Marines are revered in Kerch and Sevastopol as both the heroic defenders and the liberators of the cities from the Nazis. Legendary medic Ekaterina Mikhailova-Demina, who now lives in Moscow at the age of 88, was among those who forced the Nazi troops out of Kerch and the only woman serving in front-line reconnaissance of the Soviet marines at the time.

Ekaterina, who has been awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union and received the Florence Nightingale Medal, does not like being called heroic, but her actions in combat have served as a plot for many poems and several films. Not only did Mikhailova-Demina manage to enlist at the tender age of 15, she fought for the right to be at the very front line of the battle, even appealing to Stalin when she was not allowed to join the marines as a woman.

Amid the brutal Crimea battles of 1943-44, Ekaterina,

affectionately called Katyusha by the troops, was admired even by

the enemy. She safely took water for her injured friends from a

contested well, where people were shot daily as the Germans let

her pass. Some Germans played famous Soviet song titled

“Katyusha,” to greet her, the others shouted from the

trenches: “Russian marine! Russian Ivan! Show us Katyusha! We

won’t fire,”

While Ekaterina remembers such episodes with a smile, she also cannot forget the many dead and injured combat friends, who often called enemy fire on them for the lives and the success of other troops. A stunning 1943 photo taken by war photographer Yevgeny Khaldey right on the firing line of Soviet landing operation shows her tending to a wounded marine at the embattled Crimean coast.

Even though a success in the end, the Crimean offensive cost the Soviet troops more than 17,700 killed and over 67,000 wounded.

Mikhailova-Demina also embodies a little-remembered and little-realized role of the Soviet soldiers as the liberators of Europe. After the battle for Kerch, she fought for the liberation of Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia and celebrated Victory Day, 1945, in the Austrian capital, Vienna. The only Vienna bridge that was not blown up by the retreating Nazi troops was saved by Ekaterina’s battalion, and she recalls pulling beautiful old tapestries out of the fire with the locals.

Indeed, the only thing in the world that Katyusha wholeheartedly hates is the “cursed war.”

‘History of Crimea sacrifice runs deep in Russian psyche’

Amid the controversy with the accession of Crimea into Russia following the March 16 popular referendum, which a number of Western leaders have blasted as “annexation,” there is a small but growing understanding in the West of the region’s place in Russian culture and history. Only by studying the historical context can one understand what the places like Kerch and Sevastopol mean for the Russians and why a large part of the Russian-speaking majority of Crimea have always considered the region to be a Russian land.

In a recent article on WalesOnline, titled: “The carnage in Crimea during World War II has shaped Putin’s response to Ukraine crisis” Professor Len Scott, an expert in International History and Intelligence Studies at Aberystwyth University of Wales, argues that the enormous loss of life during the WWII battles for the Soviet Russian region “has been a factor in the equation which no-one seems to include, and which reflects our lack of knowledge of, and respect for, Russian history.”

“If you look at the sacrifices, if you look at the casualties (when of course the USSR was Britain’s ally against Germany) – that is seared on generations of Russians and the peoples of the Soviet Union. None of this explains away or apologizes for the crimes of Stalin. Yet the history of the sacrifice at Sevastopol, Leningrad, Moscow and Stalingrad runs deep in the Russian psyche. Whatever Mr. Putin’s other calculations in the Crimea, the weight of Russian history weighs down upon his shoulders,” Scott writes.

“For many Russians in the Crimea this is memory, not history. For others, it is the history of their parents and their uncles and their aunts,” he adds.

A Fellow of the Royal Historical Society, Scott is careful to support the UK government’s stance on the Crimean crisis, saying that UK Foreign Secretary William Hague is “absolutely right” in his assessment of Crimea’s “annexation” and it being a “flagrant breach of international law,” which the author says cannot “go unchecked.”

However, Scott then adds: “Crimea, it should not be forgotten, was never part of the Ukraine until 1954, when Nikita Khrushchev handed it over as a gesture to commemorate 300 years of Russian-Ukrainian relations. The people of the Crimea had no say in Khrushchev’s decision.”

The Crimean parliament applied to join Russia on March 17 after the Crimean referendum, in which 96.77 percent of voters chose independence from Ukraine. On March 21, Russian President Vladimir Putin signed the decree joining Crimea and the city of Sevastopol with the Russian Federation into law.