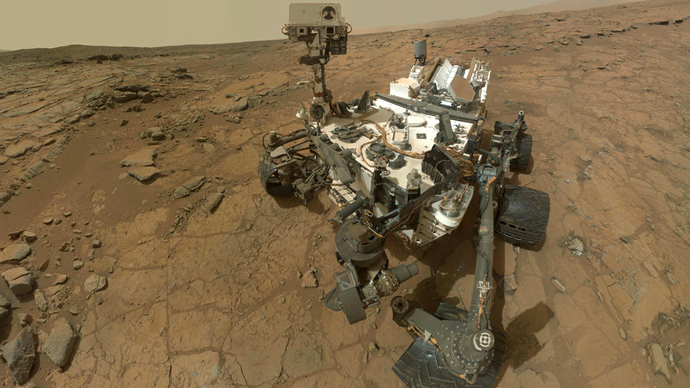

The rover Curiosity has discovered water in fine-grained soil on the surface of Mars, NASA confirmed Thursday in a series of papers published in the journal Science.

Each cubic foot of Martian soil contains about two pints of

liquid water, though the molecules are bound to other minerals in

the soil.

Curiosity first landed on Mars in August 2012 on

Gale Crater, near the equator of the planet. Its aim was to

circle and scale Mount Sharp, in the middle of the crater, a

five-kilometer-tall mountain that will help NASA understand the

history of Mars.

NASA scientists released the first detailed, peer-reviewed

results of Curiosity’s experiments done during its first four

months on Mars in a series of five papers published in Science.

"We tend to think of Mars as this dry place -- to find water

fairly easy to get out of the soil at the surface was exciting to

me," said Laurie Leshin, dean of science at Rensselaer

Polytechnic Institute and lead author on the Science paper that

verified existence of water in the surface soil.

"If you took about a cubic foot of the dirt and heated it up,

you'd get a couple of pints of water out of that -- a couple of

water bottles' worth that you would take to the gym,” she

said, according to the Guardian.

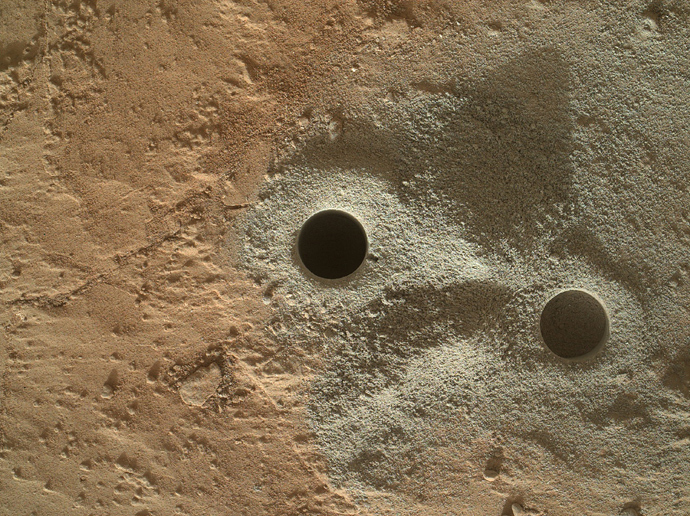

Curiosity found about 2 percent of the soil, by weight, was water

by scooping dirt samples under its wheels and depositing them

into an oven in a centralized compartment called Sample Analysis

at Mars.

"We heat [the soil] up to 835C and drive off all the volatiles

and measure them," said Leshin. "We have a very sensitive

way to sniff those and we can detect the water and other things

that are released."

The rover also found sulphur dioxide, carbon dioxide and oxygen

as soil and minerals collected decomposed with increased

temperature.

A main aim of Curiosity’s missions is to find out whether Mars

was ever hospitable to life. Scientists believe water

was once abundant on the surface of the planet, but it has since

almost completely disappeared.

"The rocks and minerals are a record of the processes that

have occurred and [Curiosity is] trying to figure out those

environments that were around and to see if they were

habitable," Peter Grindrod, a planetary scientist at

University College London who was not involved in the analyses of

Curiosity data, told the Guardian.

The other papers published in Science included x-ray diffraction

images of the soil in an attempt to examine the crystalline

structure of the minerals on Mars’ surface, and analysis of a

volcanic rock called "Jake_M,” named after a NASA

engineer. The findings show the rock was similar to a type found

on Earth known as mugearite, often found on ocean islands and in

rift zones.

The published results of Curiosity’s experiments are the

beginning of insights into Mars expected to come in the next few

years.

"It's the first flexing of Curiosity's analytical

muscles," Grindrod said. "Curiosity spent a long time

checking out the engineering, instruments and procedures it was

going to use – these papers cover just that engineering period.

The targets here weren't chosen because of their science goals as

such but as good targets to test out the instruments."

Leshin said in addition to the excitement of exploring a new

planet, the findings will help planning for any human mission in

the future.

"I do think it's inevitable that we'll send people there and

so let's do its as smartly as we can. Let's get as smart as we

can before we go,” she said.

The soil on Mars also showed the existence of a chemical called

perchlorate, which can be toxic to humans.

"It's only there at a 0.5% level in the soil but it impedes

thyroid function," she said. "If humans are there and are

coming into contact with fine-grained dust, we have to think

about how we live with that hazard. To me it's a good connection

between the science we do and the future human exploration of

Mars."