Digital arms merchants make millions on keeping computers hackable

Why would someone keep a way to make the world a safer place secret? Because keeping it unsafe is profitable. The logic works for gun-runners just as well as for hackers reportedly earning six-digit figures from governmental agencies.

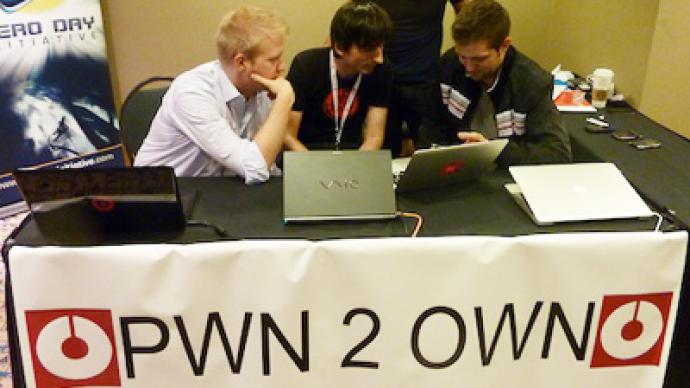

French firm Vupen Securities has a bad name in the information security industry over its taunting producers of the software they hack. Last May it clashed with Google, after demonstrating a way to take over the giant’s web browser Chrome.The confrontation was taken to a new level at the Pwn2Own competition in early March. Vupen used two zero-day vulnerabilities in Chrome, for the first time hacking it during a public event. In a zero-day attack, the hacker uses a glitch in software that is not known to the producer and thus cannot be closed by a patch. Just as before, the team refused to unveil their secrets, which means every computer running Chrome can be hacked in the same way.Vupen’s co-founder and head of research Chaouki Bekrar said the five-strong team spent six weeks preparing the attack. The firm has added their trick to a large catalogue of hacking techniques they sell to their clients, Forbes magazine says.Their prices are high enough to dwarf the million-dollar prize Google itself offered this year for hacking Chrome and explaining how it was done. According to analyst estimates, Vupen takes $100,000 annually just for the privilege of shopping for their tools.“We wouldn’t share this with Google for even $1 million,” Bekrar told the magazine. “We don’t want to give them any knowledge that can help them in fixing this exploit or other similar exploits. We want to keep this for our customers.”The customers in question are governments, which want to have an arsenal of cyber weapons at their disposal to hack into computers of suspects and intelligence targets. Bekrar claims the French firm has internal standards for screening their clients and sells hacking know-how only to NATO and NATO partners.“We do the best we can to ensure it won’t go outside that agency,” Bekrar says. “But if you sell weapons to someone, there’s no way to ensure that they won’t sell to another agency.”Vupen is hardly the only company in the business. Moreover, other players including Netragard, Endgame and larger contractors like Northrop Grumman and Raytheon keep a low profile and do not seek publicity.“Vupen is the Snooki of this industry,” explains Chris Soghoian, a privacy activist and fellow at the Open Society Foundations, referring to a character in the TV show Jersey Shore. “They seek out publicity, and they don’t even realize that they lack all class. They’re the Jersey Shore of the exploit trade.” The business is perfectly legal, even though critics say it is morally dubious. Bekrar shrugs off the insults. “We don’t work as hard as we do to help multibillion-dollar software companies make their code secure,” he says. “If we wanted to volunteer, we’d help the homeless.”