Scientists find DNA of first-ever bubonic plague, warn of new outbreaks

Scientists have reconstructed the genome of the first recorded bubonic plague and compared it to two later pandemics. New sophisticated strains of the disease that killed millions of Europeans in the Middle Ages could break out in future, they warn.

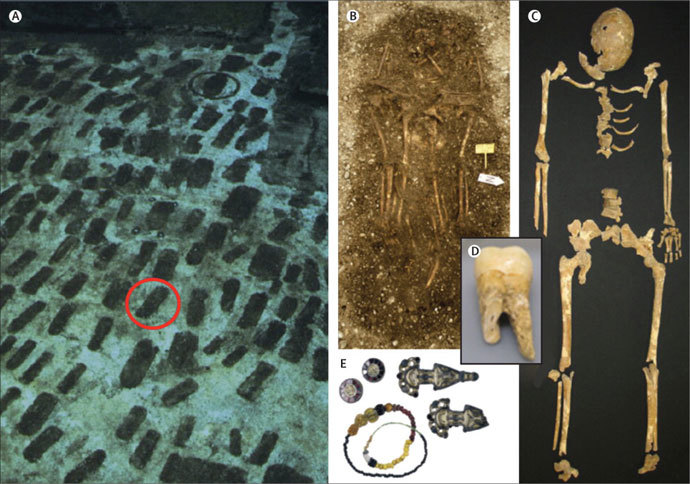

Researchers have managed to extract the DNA from the teeth of two victims of the Plague of Justinian, a pandemic that swept through the Byzantine Empire in AD 541-542, found in an early medieval cemetery in German Bavaria, according to a study published Tuesday by The Lancet Infectious Diseases.

The Plague of Justinian is believed to have wiped out up to half the world’s known population at the time. The new research clearly links the Plague of Justinian with the Black Death bubonic plague, which was spread by rats in the 14th to 17th centuries, and a later pandemic in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The research shows that what caused all three pandemics was the same Yersina pestis (Y pestis) bacterium. However, the strains of the first pandemic are sufficiently different from those of the later pandemics to prompt a warning from scientists, who believe that the same bacteria with different DNA lineages is a worrying sign.

“These results show that rodent species worldwide represent important reservoirs for the repeated emergence of diverse lineages of Y pestis into human populations,” the study concludes.

Hendrik Poinar, director of the Ancient DNA Centre at McMaster University in Canada, who led the new research, believes scientists have to keep an eye on plague in rodent populations – the disease’s major carriers – to be able to avert future human outbreaks.

While modern-day antibiotics are able to stop currently known strains of plague, the researcher has not ruled out the possibility for potentially dangerous mutations. If there ever emerges an airborne version, the plague of that type could kill people within 24 hours of being infected, Poinar warned.

"If we happen to see a massive die-off of rodents somewhere with [the plague], then it would become alarming," the scientist told AP.

The warning was echoed by Tom Gilbert, a professor at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, who wrote an accompanying commentary for the study.

"What this shows is that the plague jumped into humans on several different occasions and has gone on a rampage," he said. "That shows the jump is not that difficult to make and wasn't a wild fluke."

Plague, one of the world’s oldest known diseases, still remains endemic in mostly tropical and subtropical areas, according to the World Health Organization. A disease of rodents, it’s spread among them by fleas. Around 2,000 people a year get affected globally.

When rapidly diagnosed and promptly treated, plague may be successfully treated, reducing mortality rate from 60 to less than 15 percent, the WHO says.