It’s raining satellite: Europe’s gravity field explorer to fall back to Earth in two weeks

A one-ton European Space Agency satellite, which for four years has being mapping the Earth’s gravity, has run out of fuel and will reenter the atmosphere in two weeks. While its descent is constantly monitored, the impact location is still unknown.

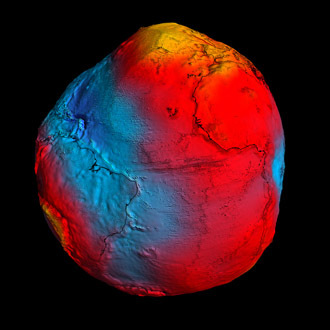

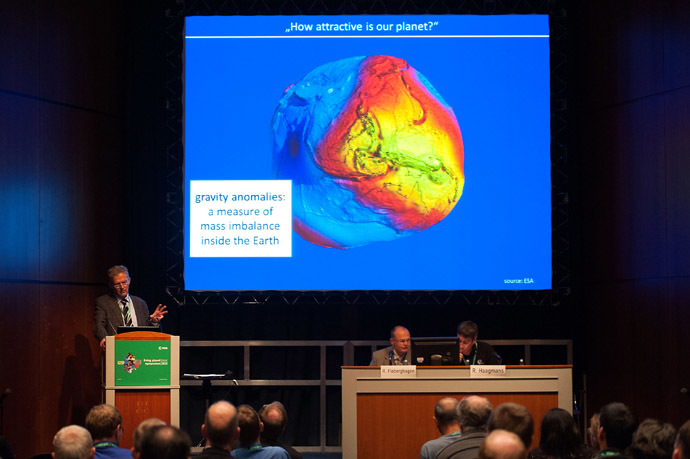

The ESA’s Gravity field and steady-state Ocean Circulation

Explorer (GOCE), which was launched from Russia in March 2009,

managed to spend 2 1/2 more years on its mission than was

initially expected. During these extra years of work, it was

taken to the lowest altitude orbit of any research satellite to

capture the gravity data of unequalled accuracy.

On Monday, GOCE’s supply of xenon fuel was finally depleted and

the ESA declared the mission over.

The work of the flight control team did not end with that,

though, as the 1,100 kilogram satellite will still be orbiting

for about two weeks, before its system stops working and it

plunges back into the atmosphere from an altitude of 227

kilometers (139 miles).

The last part is particularly tricky, as even with all the latest

technologies available, the space agency is unable to predict

where parts of GOCE might fall.

While most of the satellite is expected to burn up during

reentry, Reuters reports that as many as 50 fragments with a

total mass of up to 275 kilograms have been predicted to reach

the surface and splash into the ocean – or hit land.

“When and where these parts might land cannot yet be

predicted, but the affected area will be narrowed down closer to

the time of reentry,” the ESA said in a statement on its

website.

Such uncertainty is caused by constant changes in the upper

atmosphere, which are strongly influenced by solar activity.

An international campaign involving the Inter-Agency Space Debris

Coordination Committee is monitoring the situation continuously,

the ESA said, promising to “keep the relevant authorities

permanently updated.”

Space agencies usually consider the risk of someone being hit by

a piece of space junk as extremely low, although this assumption

is based on the fact that only a tiny fraction of the planet’s

surface is densely populated.

According to NASA’s data, based on 50 years of observations, each

day an average of one tracked piece of orbital debris falls back

to Earth. The agency states that so far “no serious injury or

significant property damage caused by reentering debris has been

confirmed.”

However, when the 13-ton Russian probe Phobos-Grunt unexpectedly

failed to boost its engines in near-Earth orbit and started

slowly descending for its final downfall in January 2012, it sent

chills down the spines of many space-watchers. Luckily, most of

the probe’s debris eventually landed in the Pacific Ocean.

Phobos-Grunt’s failure was not the first uncontrolled fall of a

huge manmade object from space. In September 2011, NASA’s 6-ton

Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite plunged back to Earth with

“a small potential risk to the public.” The largest of the

parts that might have reached the surface was estimated to weigh

160 kilograms.

NASA’s satellite was later confirmed to have fallen in the

Pacific several hundred kilometers away from American Samoa. Just

a month later it was followed by Germany’s 2.4-ton X-ray ROSAT

telescope, which was feared to survive in chunks as heavy as 400

kilograms. None of the chunks were reported to have reached the

surface following reentry, however.