EU tax dodgers rob poor countries of $100bn per year - NGOs

European NGOs claim the EU’s failure to curb tax avoidance is costing developing countries at least $100 billion per year as firms fail to fulfill their legal obligations.

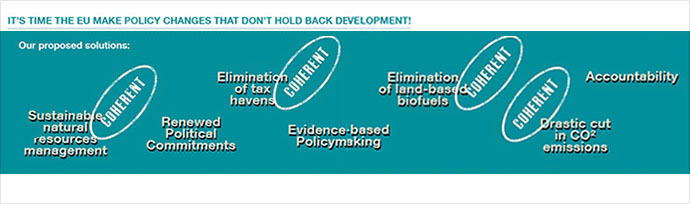

CONCORD, a group of European NGOs, called for action in its new report. It urged rich countries to stand up against tax avoidance, thereby allowing developing countries to retain their share of tax revenues.

Tax has turned into a key issue for developing nations, with Nigerian finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala and former UN head Kofi Annan asking rich countries to do more to fight against tax avoidance and illicit flows.

Developing countries lost nearly $859 billion in 2010 alone. That number is 13 times more than the EU spent on development aid in 2012.

“The EU is the biggest donor of the development aid, but, at the same time, it implements several policies that undermine development in developing countries and tax avoidance is one of the major problems,” chair of CONCORD's working group on Policy Coherence for Development (PCD), Laust Leth Gregersen, told RT.

The CONCORD group argued that the EU could be doing more to fight against tax dodging, stating that its current mechanisms for finding and correcting incoherent policies are ineffective.

"Europe cannot continue to give aid with one hand and take away with the other, and tax policy is a classic example of where it's doing this," Gregersen told The Guardian. "Billions go to poor countries in aid only to return again to rich countries via tax dodging. The balance sheet shows that the poor in developing countries are losing out here."

The EU is the only region that has a legally binding commitment to PCD, as outlined in the Lisbon Treaty.

Unexplored and shortsighted policies

The report states that most of the potential and actual development impacts of EU policy are not researched. Out of 177 impact assessments carried out between 2009 and 2013 by the EU commission and relevant to developing countries, only 19 percent looked at the potential impact on development objectives, according to the report.

“For example, we have a case with a lady from Zambia, selling sugar products at her stall. And that actually shows that she pays 90 times the share compared to income than the sugar company, which produced the product that she sells,” Gregersen told RT. “Part of the reason why the sugar company pays such low taxes is because of loopholes in the regulatory regime internationally, but also [because of] European tax regulation.”

And when there is knowledge that specific EU policies are having a negative impact on poor countries, there is still no “robust redress mechanism to trigger the revision of harmful policies,” the report stated. "Far too often, we observe confusion around what PCD really means, and a tendency to drop the 'D' [development] and focus merely on the co-ordination of departments and policies.”

CONCORD board member Rilli Lappalainen told The Guardian that "the EU is all talk when it comes to improving the record of its own policies for the benefit of the world's poor,” adding that it “jeopardizes the development potential of many poor countries because of incoherent, short-sighted and self-centered decisions made at home."

The CONCORD group asked EU countries in the report to share the exchange of tax information among European countries with the developing world. "The EU should support a multilateral regime for the automatic exchange of tax information that sets the highest standard and that allows developing countries such as Zambia to be included and to access the fiscal information they desperately need," the group stated in the report.

The report also pointed out that developing countries lack a voice on the international stage when it comes to taxes.

Gregersen said the CONCORD group is recommending the EU “to clamp down on tax havens” and account for “legislation and financial regulations.”

In response to the report, the European commission stated that “there is solid evidence that much has been done” to curb tax evasion. The comment pointed to the adoption of new legislation in June on country-by-country reporting, which compels large companies in the extractive industry to publicly disclose payments larger than $135,000 to their governments.