Fuel rod removal: Fukushima’s most dangerous operation yields first successes

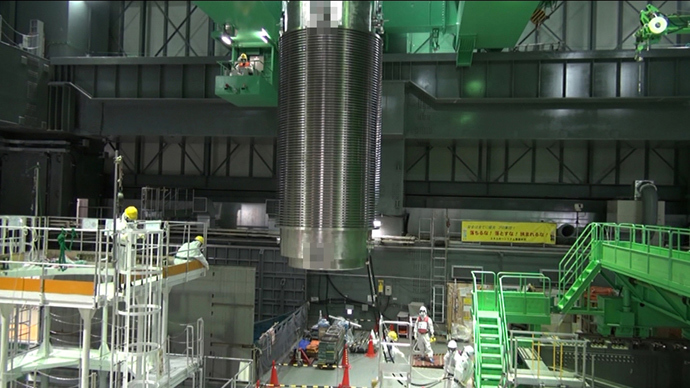

Workers at the Fukushima nuclear power plant have successfully removed the first nuclear fuel rods from a cooling pool suspended above ground in what is one of the most dangerous operations ever attempted in nuclear history.

Already riddled with problems,

the complex process of cleaning up and decommissioning the plant

consists of many components. The removal of these rods is of

paramount importance for safety and the prevention of another

nuclear catastrophe.

Each fuel assembly contains 50 to 70 fuel rods – there are a total of 22 assemblies that have been transported today aboard a trailer to another, newer, storage pool on the final day of an operation that lasted four days, according to a statement by Tokyo Electric Power Co (TEPCO), Reuters reports.

What used to be done by computer will now be an entirely manual process, because of the tilted position of the cooling pools, which was affected by the tsunami and earthquake that battered the power plant in 2011.

The reason is that computers are programmed only to respond to the exact position of a fuel rod. With those positions now offset, the operation is a painstaking manual process. Each time the fuel rods rub together or are subjected to shaking, the workers risk unleashing incredible amounts of radiation.

There are more than 1,500 potentially damaged fuel assemblies located in Reactor No. 4 – the most unstable part of the power plant. It was offline at the time of the 2011 catastrophic earthquake and tsunami, which is why, unlike the other three, its core didn't go into meltdown. Instead, hydrogen explosions blew the roof off the building and severely damaged the structure – a wholly different problem.

Now it is up to the cranes, controlled manually by workers, to do the job.

By TEPCO’s estimates, the reactor alone should take about a year to decommission, but some experts say even that may not be enough time.

And time is the one thing TEPCO may not have. Mini-earthquakes and tremors are frequent in the area, let alone big natural disasters. So with time and accuracy being important, many see the operation as a test of how well the plant operator can handle the entire decommissioning process.

The operation will have to be performed underwater, for even exposure to air – not only breakage – spells trouble, as it could release incredible amounts of radioactive gas into the atmosphere (the combined radioactive yield of all the rods is more than that of the Hiroshima bomb).

Each assembly weighs about 300 kilograms and is approximately 4.5 meters in height.

Arnie Gunderson, a veteran nuclear engineer and the director of Fairwinds Energy Education, told Reuters that the whole operation was akin to pulling cigarettes from a crumpled pack.

The Monday operation had workers slowly control cranes and pulling the assemblies out one by one before they were transferred to a specially built steel cask to shield the plant workers from radiation. That cask was then taken to another cooling pool – possibly the only part of the entire power plant that was not damaged in the quake and tsunami.

However, Reactor No. 4 had it easy. Other reactors that sustained heavy damage and were subject to meltdowns also contain fuel assemblies that will need to undergo similar procedures, but it will all be much more difficult.

As this is taking place, the plant continues to be plagued by the same problems it has suffered since the catastrophe: radioactive water seeping into the ocean, a lack of adequate storage space for it, the risk of tremors or quakes and rising radiation levels.

The cleanup of the plant and the surrounding Fukushima prefecture will cost tens of billions of dollars and is expected to take decades, already causing a huge drain on the government’s resources, which stepped in after it became apparent TEPCO could not handle the costs on its own.