Iraqi lives in danger from gas-smuggling greed

In northern Iraq, the greed of smuggling gangs is putting health and livelihoods of the locals’ under threat due to illegal trafficking of gasoline from Iran into the country.

100 miles northeast of Baghdad, a special Iraqi police unit makes its way to the Iranian border. They are hunting a new breed of smugglers, who trade not in guns, but in gasoline.

A cache of confiscated jerry cans contains thousands of gallons of gasoline that was illegally trafficked from Iran.

A few days ago, smugglers floated the cans down the Sirwan River where they were intercepted by the Iraqi police.

But many of the jerry cans did not make the journey intact. Punctured by rocks or shot at by the Iranian police, tens of thousands leaked their contents into the Sirwan River, poisoning the water supply used by 35,000 residents of the city of Darbendixan.

“These are the cans that are left over,” said local Mullah Majid Ali. “Years ago the people from Darbendixan could use this water, but now because the smell, taste and color it’s too dirty and people can’t use it anymore.”

But the money is too tempting for the local smugglers, who can run 10,000 jerry cans on an average night. For a few hours of work, they can make up to $6,000.

While the smugglers line their pockets, downstream fishermen are watching their livelihood disappear.

“Two years ago we could catch twice as many fish,” recalled fisherman Ibrahim Dara.

“Two years ago in a day we would catch 20 kilos of fish,” said his colleague

Mohammad Fatah. “Now it’s only five.”

In the city, families unable to afford their own well have to drink the foul smelling water, delivered to them by municipal trucks.

On the outskirts of town, Hiwa Karim is forced to supply his family with this water:

“It’s not for drinking, but because we can’t afford clean water we have no choice but to drink it,” Karim claimed. “One of my children got sick last night. She was vomiting, so I had to take her to the hospital. When we drink the water, we get sick.”

According to the recommendations of the American Environmental Protection Agency, pollution levels in the water supply are over 15 times higher than safe amounts.

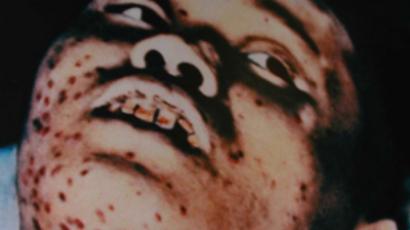

In Derbandixan Hospital, Narmin Abdul Rakhman’s daughter is suffering from diarrhea, which she contracted after having a bath in the city’s tap water.

“I haven’t been hospitalized myself, but because of my child I come often,” Rakhman said. “I have two other children and they suffer from diarrhea and vomiting as well. It always comes back. We’ll go home, but in a week we’ll be back here again.”

And with the same regularity as Narmin’s visits to the hospital, the smugglers continue to spill gasoline into Derbandixan’s water system.