Khodorkovsky: I’m not interested in power or lost Yukos assets, but care about people

The assets of the fallen oil giant Yukos and political power are of no interest for Mikhail Khodorkovsky, the company’s former CEO says, but he cares about the people he worked with at the time.

Follow RT's LIVE UPDATES on Khodorkovsky’s release.

Khodorkovsky, who was released from a Russian prison Friday after spending 10 years behind bars, was outlining his plans Sunday to journalists in a media conference and several interviews.

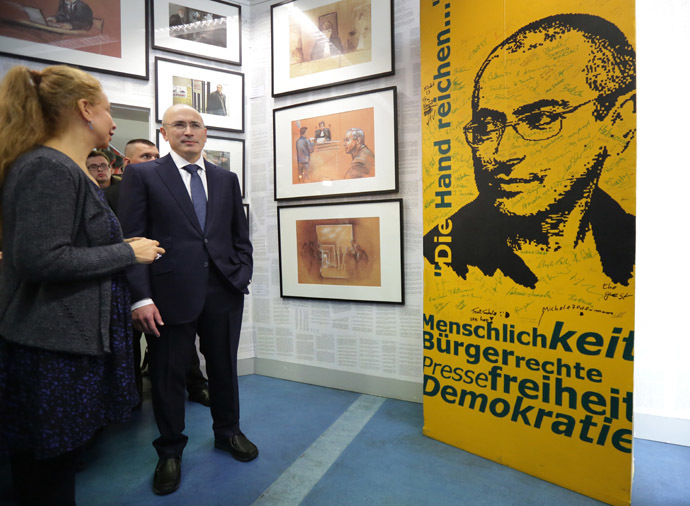

“I'm not planning to be involved in politics, which I've already made clear in my letter to President Putin, and confirmed many times," he assured a small group of journalists at the Berlin Wall museum. Khodorkovsky added that he may do some work to seeking the early release of those he considers political prisoners, whether they are his former Yukos colleagues or otherwise.

Khodorkovsky also said he personally will not fund any Russian political parties or forces the way Yukos did in the past, explaining that such funding could actually hurt them, on the one hand, and that on the other, he doesn’t even know his financial circumstances at the moment.

Khodorkovsky has enough money to provide for his family, he said.

“If I needed money, I would have started a business, but at the moment I definitely have enough for living. I don’t buy football clubs,” he said.

My father's press conference in Berlin pic.twitter.com/BSeypNsFqt

— Pavel Khodorkovskiy (@pmhburyatia) December 22, 2013

As for the disputed assets of Yukos, he is not planning to do anything to return them to shareholders, Khodorkovsky told Dozhd (Rain) TV’s Ksenia Sobchak in an interview from his hotel room Saturday evening.

“I personally won’t take any part in this and will have no interest in whether Yukos shareholders win or lose in [lawsuits over the company’s assets]. This issue is closed for me,” he said.

Khodorkovsky’s decision to appeal for clemency came after he was assured that he would not be required to admit his guilt, he said.

Such an admission “was not acceptable to me, for a very practical reason,” Khodorkovsky said. “Not because I was interested in how the press would cover it, but because – given the approach to this by the investigation, as well as our country’s legal system – all of Yukos, anyone employed there, could be formally considered an accomplice as a member of an organized crime group, based on Mr. Khodorkovsky’s first failing to pay oil revenue taxes in their entirety, then stealing that oil.”

Asking for a pardon per se was never an option he rejected, Khodorkovsky said, so when former German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher informed him through his lawyer on November 12 that he could apply for one without an admission of guilt, he did so.

Aside from an official plea, Khodorkovsky also wrote a personal letter to President Putin, in which the former oligarch argued for his release and described his plans and ambitions for the future, he said. He said the letter’s contents were not secret, and in it he reiterated what he had told the media previously, “except for issues I don’t want to voice for family considerations.” Khodorkosvky added that he was grateful to President Putin for not publishing those details.

When asked whether he holds any grudge about his situation, Khodorkovsky said: “I would be bending the truth if I said I had no feelings at all about it, but I am doing serious work on myself, because I have always thought that looking back is wrong and unnecessary.”

In a separate interview with The New Times magazine, Khodorkovsky provided some details of his release from prison in the early hours of Friday morning. He said he was expecting it to happen pretty soon after hearing media reports Thursday about Putin’s intention to pardon him. So it was no surprise that he was requested by the prison authorities to prepare for release early Friday morning.

He was taken out of the prison by the head of the Federal Penitentiary Service’s Karelia department, who had the authority to expedite his release before all the paperwork was complete. Then he was taken by car to an airport in Petrozavodsk, the nearest to the prison. From there a government plane took him to St. Petersburg, and a few hours later he boarded a jet to Germany.

Khodorkovsky’s rapid release and journey to Berlin took many people by surprise. When the presidential decree pardoning Khodorkovsky was made public on Friday morning, journalists traveled to the prison, not realizing that he had already left.

It also posed some practical difficulties for Khodorkovsky, because his lawyer didn’t have time to bring him new clothes. He got to St. Petersburg in his prison clothes and was there given an aviator’s jacket by airport staff. He is shown wearing that jacket in all the photos, he said.

Khodorkovsky explained that he knew at the time of his release that his mother was in Russia, but he still asked for an opportunity to immediately go to Germany.

“The situation is that back on November 12, mom was in a Berlin hospital. Thankfully, two weeks ago doctors told her she could return to Moscow for three months, but after that she had to go back to Berlin. Thank God for giving her this break. But it meant that we [just] missed each other,” he said.

In the same interview, Khodorkovsky denied media reports that his release had been brokered by secret agents. He said there were no strings attached to his pardon plea, and that he and the Russian authorities had an unspoken understanding about what he is going to do in the future.

He also commented on speculation that he may never return to Russia, despite the assurance from Putin’s spokesman, Dmitry Peskov, that Khodorkovsky is free to come back to Russia whenever he wishes. The former magnate confirmed that he was worried that Russian authorities may choose to ban him from traveling abroad if circumstances change.

“Objectively speaking, I will come back only if I am certain that I would be able to go back and forth as I need. With my current family situation, it’s the main condition,” he said.

At the closed-door meeting with journalists, Khodorkovsky said that there exist legal grounds for such a restriction on his travel, because there is a lawsuit against him demanding half a billion dollars in damages he caused.

“Judicially speaking, the lawsuit based on my first case is not closed. The lawsuit is for $550 million, and Russian law makes it possible to stop me from leaving the country over this,” he said.

He said he would be waiting for Russia’s Supreme Court to rule on the lawsuit, and if it is overruled, it would be “a sign demonstrating that I can come to Russia,” Khodorkovsky said.