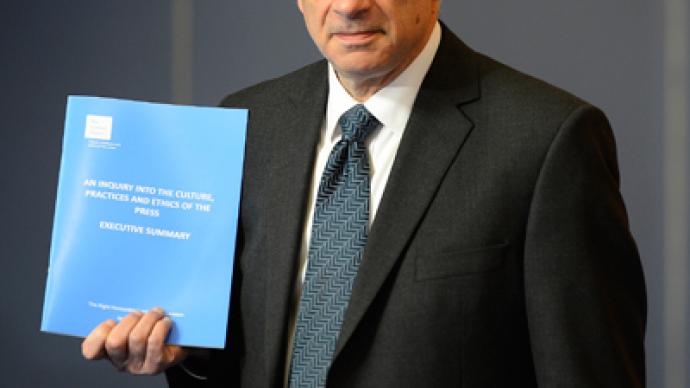

Leveson Inquiry verdict: UK needs press watchdog

The Leveson inquiry into the UK press recommends a new independent regulatory body free from government control, which the press themselves would sign up to. However, he also recommends legislation, which Prime Minister Cameron stands against.

The main outcome of the 16 month Leveson enquiry was a recommendation that a new press watchdog must be formed, independent of parliament and the media, which is underpinned by statute. It should be free of “any influence from industry and government” and “should be governed by an independent board”, he said. The body “must be appointed in a genuinely open, transparent and independent way,” he continued. While Leveson said the new independent regulator should be organized by the press themselves it “should also place an explicit duty on the government to uphold and protect the freedom of the press.”It was this suggestion that was met with condemnation by some and caution by others, including the Prime Minister. The editor of the Spectator, a satirical weekly magazine, vowed not to comply with any statutory regulator, while the director of civil liberties group Liberty, Shami Chakrabati, cautioned that no one needs a “last resort compulsory statutory press regulation – coming at too high a price in a free society.”

But the new body, recommended Leveson, must have more teeth than the Press Complaints Commission (PCC), which it will replace. It should be able to impose fines of up to 1% of turnover or £1 million and have “sufficient powers to carry out investigations both into suspected serious or systematic breaches of the code.”The regulatory body should also have an arbitration process to deal with civil legal claims against the press but that “frivolous and vexations” claims could be thrown out at an early stage. One of his most surprising recommendations was that membership of the new body should not be obligatory. In such cases newspapers would be policed by the broadcast watchdog Ofcom. Leveson concluded that a culture had developed in some quarters of the British press which encouraged “a recklessness in prioritizing sensational stories, almost irrespective of the harm the stories may cause and the rights of those affected.”He continued that there was “ample evidence” that certain parts of the press had decided that celebrities were, “fair game, public property, with little if any entitlement to any sort of private life. Their families, including their children, are pursued and important personal moments are destroyed.”He also rejected the claim of Paul McMullan, a former feature writer at News of the World, that “privacy is for paedos.”

He saved his most venomous criticism for the treatment of the victims of family tragedy by some newspapers. He derided the News of the World who hacked the phone of a murdered school girl and accused various tabloids of “outrageous behavior” in their handling of the disappearance of the missing school girl, Madeline McCann from Portugal in 2007. He singled out a particularly offensive headline by the Daily Star, which read “Maddie sold by hard up McCanns.” David Sherborne, a lawyer representing the 51 victims of phone hacking, advised that if the press fails to create an independent regulator this parliament must impose one. But in a speech to the commons on Thursday, Prime Minster David Cameron was more cautious. He welcomed Leveson’s proposals of how a new regulatory body should operate and told the House, “The onus should now be on the press to implement them radically.”But Cameron warned that there were some areas of Levesons’ recommendations, which sounded alarm bells. In particular he singled out proposed changes to the Data Protection Act that would reduce special treatment that journalists are provided when dealing with personal data and the effect that this might have on investigative journalism. He also systematically rejected the principle of “writing press regulation into the law of the land.”The 16-month report looked at why politicians and police failed to react when reports first appeared of phone hacking cases linked to The News of the World. Critics argue that the power of Rupert Murdoch’s media empire was so far-reaching that the Press Complaints Commission (PCC) and the authorities were powerless to take action.But in an example of the benevolent power of journalism, a lengthy investigation by the Guardian into the phone hacking scandal forced Cameron to open the Leveson inquiry.The inquiry is estimated to have cost around US$9.5 million and is supported by a backlog of interviews with media figures and celebrities who were targeted in the phone hacking scandals.Meanwhile, Rebekah Brooks, the former News International chief executive and Andy Coulson, former editor of News of the World, were released on police bail Thursday facing charges of corrupt payment to officials.