Martian freshwater lake may have supported life - NASA

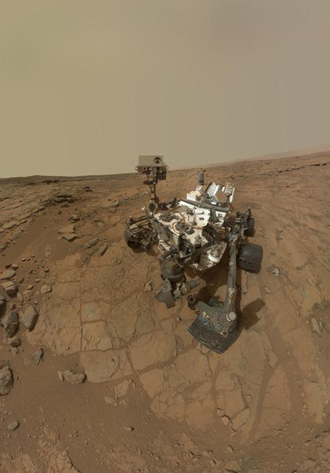

NASA says Curiosity rover has found signs of an ancient freshwater lake on Mars that existed 3.5 billion years ago and may have supported small organisms for tens of millions of years, but doubts remain of the origin of the organic matter.

The findings were published Monday on the NASA website and in the journal Science and were presented at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco and relate to a site on Mars called Gale Crater in Yellowknife Bay. The site was first drilled by Curiosity ten months ago.

Curiosity analyzed sediment from the bed of a long vanished lake and found that it harbors substantial amounts of organic matter of some sort, although scientists have pulled back from attributing it to life.

It is thought possible that over 4 billion years ago Mars may have had enough fresh water on its surface to generate clay minerals which may have supported life but that it underwent drying that left any remaining water too acidic and briny to support life.

Curiosity has also determined how recently surface rocks have been exposed by erosion.

“Our mission is turning a corner. We are beginning to map a way forward, a way to explore deliberately for organic matter,” Said John Grotzinger, a Curiosity project scientist at the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

But Mark Sephton from Imperial College London, who is not on the Curiosity Team, was more skeptical as to the origin of this organic matter.

Tons of organic matter falls on Mars every year in the form of meteorites and cosmic dust and researchers estimate that these organic compounds made by chemical processes in space may have supplied the Martian surface with between ten parts per million (ppm) and several hundred ppm of carbon. This they say would account for the 500 ppm of carbon found by Curiosity in the lakebed samples.

The environment around Gale Crater in Yellowknife Bay where Curiosity made the discovery does not appear to have been very hospital to life says Curiosity team member Scott McLennan of Stony Brook University in New York.

He told Science that deposits washed into the crater from higher ground show very little evidence of chemical weathering, which suggests there was little water around to alter the minerals and likely the environment was very arid and/or cold like the extremely arid Atacama Desert in Chile, where water flows only when there is a rare torrential downpour.

While Grotzinger describes the mud found by Curiosity in the bottom of the crater as a “strikingly earthlike habitable” environment the article in Science points out, that in the absence of oxygen any microbes would have had to derive energy from the chemical imbalances between minerals in the sediment, a process known as chemolithotrophy.

On earth convincing evidence of chemolithotrophy has only been found in rock kilometers underground in South African Gold Mines but scientists now believe they have found a solution to test for chemolithotrophy on Mars and identify rock that has been buried for billions of years. The technique involves analyzing how wind erosion can sandblast away overlying rock and expose the rock beneath, giving researchers a clue as to what was there between 30 million and 110 million years ago.

This will enable Curiosity to look for signs of recent wind erosion and then see how freshly exposed the rock is.

“It gives us a rational way to look for organics on Mars,” said Grotzinger.