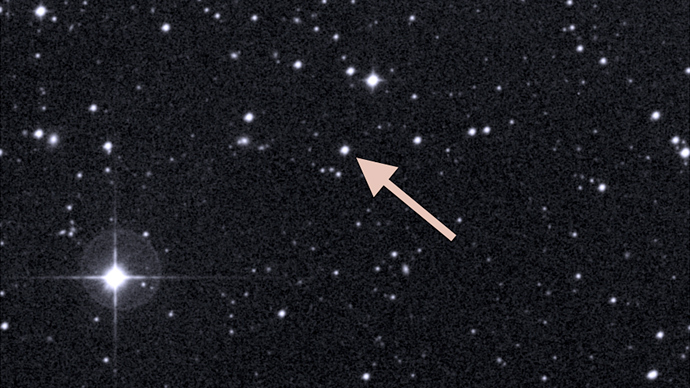

Australia’s SkyMapper telescope discovered oldest known star

Australian astronomers are positive they’ve discovered the most ancient star to date. Being practically three times older than our Sun, the old-timer star could serve as a prototype system to explore matter metamorphose in the universe.

Spectral analysis of the composition of the newly-discovered star shows it formed approximately 13.6 billion years ago, shortly after the creation of the universe. Modern cosmological science maintains that our universe came into being as a result of a Big Bang event some 13.7 billion years ago. Our Sun is approximately 4.57 billion years old.

The new star beats the previous longevity record of 13.2 billion years set by a star dubbed HD 140283 surveyed by American astronomers.

This old star - catalogue number SMSS J031300.36-670839.3 - was found in our own Milky Way galaxy. It has a mass 60 times bigger than our Sun and is relatively close to us, some 6,000 light years from Earth.

The star was spotted by the Australian National University's SkyMapper telescope at the Siding Spring Observatory, which is on a five-year mission to map out the stars of the southern hemisphere.

Skymapper, which started operating in 2009, is a fully automated optical telescope in northern New South Wales. During the first year of survey operations, SkyMapper photographed over 60 million stars, and this ancient one, currently in the focus of attention, is one of those.

Dr Stefan Keller, head researcher at the Australian National University in Canberra, told Reuters that after 11 years of searching, his team had finally seen a unique chemical fingerprint of the star that was among the very first ones in the universe.

“It's giving us insight into our fundamental place in the universe. What we're seeing is the origin of where all the material around us, that we need to survive, came from,” Keller said.

The astronomer explained that unlike younger stars, primordial ones do not contain iron, because in its early stages the universe contained only light chemical elements, such as hydrogen, helium and lithium, whereas heavier ones were formed within the star’s cores later.

“What that means is we had a long-held theory that the first stars to form would be extremely massive because they are formed out of pure hydrogen and helium,” said Keller, adding that ‘spectral portrait’ of the newly found ancient star reveals traces of pollution with light elements like carbon and magnesium, but has no sign of iron whatsoever.

“A star is like an onion - it has all these layers and the heaviest material like iron is right down in the core,” Keller said. This means that every new generation of stars would contain more heavy chemical elements, such as iron. This means that the less iron there is in the star’s light spectrum, the older it is.

The birth and death of stars is a constant process as new ones are formed from the gas and dust left from explosions of huge supernova stars that explode at the end of their life circle.

“The only thing to come out of it (SMSS J031300.36-670839.3) was the carbon and a little bit of magnesium from that supernova and that's what we're seeing today in the star that we've discovered,” the astronomer specified in a letter to the AFP.

“This is the first time we've unambiguously been able to say we've got material from the first generation of stars," Keller said. "We're now going to be able to put that piece of the jigsaw puzzle in its right place,” the astronomer told Reuters.