In a breakthrough discovery, US scientists found a distinctive ‘signature’ on the brain when specific types of pain are felt. This new ability to ‘map’ pain could be used to determine the kinds of pain are felt by patients unable to articulate it.

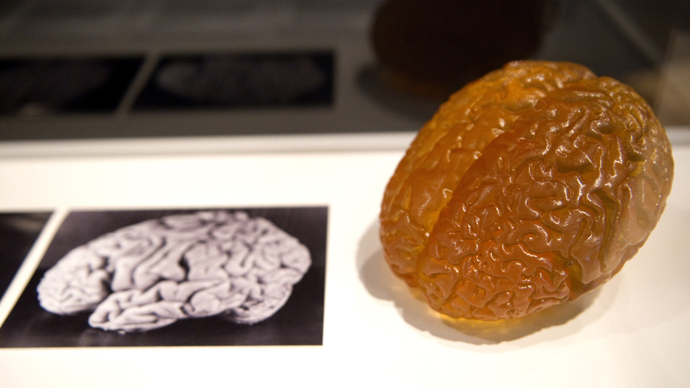

Scientists could ‘see’ the pain experienced just by looking at a

brain scan after taking real-time images of the brain’s immediate

response, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). When

researchers gave participants a painful ‘dose’ of heat, the fMRI

charted blood flows through the brain, leaving a pattern – or

‘signature’ – of brain activity.

The study involved 114 healthy people, and was published in the

New England Journal of Medicine on Thursday.

The ‘neurological signature’ was used to predict subjective pain

experiences with over 90 percent accuracy. Scientists devised an

algorithm that could calculate this correspondence of brain images

to the actual degree of pain felt.

“Right now, there's no clinically acceptable way to measure

pain and other emotions other than to ask a person how they

feel,” said Tor Wager, lead author of the paper.

The results of the discovery could be used to monitor the pain

felt by people who are unable to express it, and even bring an end

to subjective patient self-evaluation of their own agony.

Experts have said that the experiment’s findings could also pave the way to objective measurement of people’s pain on a real scale. In present times, patients usually rate their own pain on a scale of 1 to 10, a method that is often deemed unreliable. “Persistent pain is measured by means of self-report, the sole reliance on which hampers diagnosis and treatment,” the study’s background explained.

Heat-induced and emotional pain on scanner

Scientists were able to determine reactions to only certain

types of painful feelings.

For once, heat-induced pain could be separated from regular

warmth, pain anticipation and emotional pain, with researchers

concluding that it “is possible to use fMRI to assess pain elicited

by noxious heat in healthy persons.”

The intensity of pain visibly subsided when pain relief was

administered.

Emotional pain was also measured: Some subjects who had recently gone through relationship break-ups were shown pictures of their former partners, or ‘rejecters.’ Scientists applied the ‘pain signature’ to determine how participants responded to what they called ‘social pain.’

“There are many ways to extend this study,” Wager said,

offering a possible path for future research: “Is the predictive

signature different if you experience pressure pain or mechanical

pain, or pain on different parts of the body?”

Additionally, the issue of mapping chronic pain over the

lifetime of an individual is yet to be addressed, such as with

persistent migraines or fibromyalgia. Researchers do not yet know

whether this ‘signature’ would appear in people with these

afflictions.

Pain lie-detector?

However encouraging the results of the experiments are,

researchers still point out that the study’s consequences should

not be used to devalue people’s perception of their own pain.

“This is not a pain lie-detector test, and it should not be used

that way,” Head Researcher Tor Wager said. “People in pain

need to be believed.”

The incoming president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine, Lynn Webster, aired some concern to National Public Radio.

“The bad scenario would be you come in in pain, the physician

scans your brain and says, 'Well, we don't see the pain here so we

think it's in your mind. ... We don't think it's really pain,’”

she said, also explaining that insurance companies could use these

results to avoid paying for drugs.