Palestinian property – more than mortgages at stake

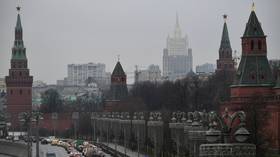

Russia's foreign minister is in Israel to help push for direct Middle East negotiations. Sergey Lavrov has already met with Israel's Foreign Minister and the leader of the Palestinian Authority.

The visit is aimed at getting Palestinian-Israeli indirect talks back on track, after having been hampered by last month's naval raid on a Gaza-bound flotilla that led to the deaths of nine Turks.

During a meeting with Israel’s Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman, Lavrov spoke of Russia’s plans to maintain contacts with Hamas in order "to promote the position of the [Middle East] Quartet and the whole world community."

Another stumbling block to peace is the expansion of Israeli settlements in East Jerusalem.

On Monday, Palestinian demonstrators clashed with forces and many have condemned Israel's plan to build new homes there.

Some Israeli settlers are so desperate to stay in the settlements that they plan to take up Palestinian citizenship.

One of them is refugee settler Avi Farhan. He was born in Tripoli and forced to flee when the State of Israel was established and the Libyan government urged Jews to leave. Then, in the early 1980s, he was taken from his home when Israel returned Sinai to Egypt. Five years ago, he was again kicked out of his Gaza settlement, despite his wish to live under Palestinian rule.

“If it's real peace, there's no reason on Earth why Jews cannot continue to live in these places, just as they do in any city in the world,” Avi Farhan maintains.

“I sent a letter to the White House in 1979 asking to be able to become an Egyptian citizen. I contacted the leadership on both sides in 2005 to stop them from expelling us from Gaza. There were 17 families like mine who were willing to take Palestinian citizenship if necessary,” remembers Farhan. “I keep telling the Jews of the West Bank that this is the way to resolve the situation,” he said.

But many settlers do not want to live under Palestinian rule and be part of a future Palestinian state. They would rather Israel incorporate them as part of a future peace deal. They are not too worried because, despite the freeze on settlement building, their government insists it is keeping this land, which Palestinians claim is theirs.

Ironically, says the mayor of Efrat Settlement, Oded Revivi, in fact the property prices have been pushed up by the Israeli government’s settlement freeze. Today there is simply not enough space for the number of people who want to live there.

“Seeing how Arab nations deal with different disputes, dealing with people who have different views, people with different beliefs and different religions, I personally would not like to live in such a state and as I said, I know that a lot of the Palestinians who are neighboring with us in good relationship prefer to be on our side of the border than on that side of the border,” Oded Revivi says.

There has not been much enthusiasm from either Israeli or Palestinian leaders to the idea of Israeli settlers living in a future Palestinian state. They often dismiss the idea as a gimmick used by the settlers to try and save their homes.

Secretary General of the Palestinian National Initiative, Dr Mustafa Barghouti, says the fundamental question is, “Who does the land belong to?”

“They are most welcome if they can prove that their settlements or houses are not on land that was stolen from Palestinians and that they are not thieves of land. They can stay and they can have Palestinian citizenship,” Dr Mustafa Barghouti promised, but added that “If Israel continues settlement activity as of today, it is consolidating a situation of apartheid, to have two different sets of laws, one for Israeli settlers and one for Palestinians.”

The question of what to do with the settlements is unlikely to be answered by indirect talks on the go between Israelis and Palestinians The talks were agreed to in March but were suspended when Israel announced plans to construct some 1,400 housing units in East Jerusalem.

Most people involved are not too optimistic that the latest round of indirect negotiations will achieve anything. US Mid-East envoy George Mitchell spends his time shuffling between Ramallah and Jerusalem. But whereas nearly a-year-and-a-half ago, Israeli and Palestinian leaders were meeting directly, now they have a deadline of just four months to hammer out an agreement apart.

“If proximity talks go well, I’m sure we will get to direct talks. If direct talks happen, then that will be a major indicator that we are going in the right direction,” acknowledged Dr Sabri Saidam, deputy speaker of Fatah and former advisor to President Mahmoud Abbas.

In the meantime Avi Farhan and other displaced settlers have nowhere to go. They worry that if the latest round of talks fails, there will soon be more settlers facing the same uncertain future.