Treatment of rare diseases a zip code lottery in Russia

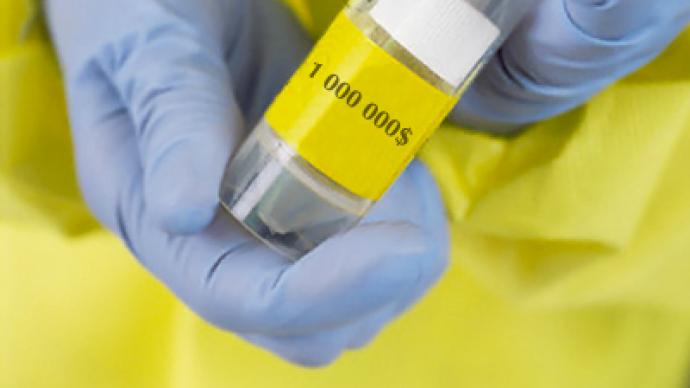

It is every parent's worst nightmare, their child being diagnosed with a rare and disabling disease. There is a treatment, but at almost a million dollars a year, it turns out to be one of the most expensive in the world.

RT first met Volodya in February this year. His birth certificate said he was 14 years old, but he looked half that age. His hearing was rapidly declining, his vision has almost gone. He responded only to the soft strokes of his mother who gave up everything to care for him.“I’m happy just to wake up and see him breathing,” the boy’s mother Elena Kotova says. “Sometimes he smiles, and it’s the greatest thing for me.”He was not always this way. At the age of five, he knew by heart a poem his mother used to read to him. He was active and affectionate. He liked cats and talked about being a driver.Then, step by step, his health began to deteriorate. His growth slowed down and cognitive abilities regressed. His mother rushed from one doctor to another until last year he was finally diagnosed with Hunter syndrome – a genetic condition that means his body cannot get rid of toxins. It is extremely rare and extremely expensive to treat – so much so that the most common advice Elena heard from doctors was to have another child. But she refused to give up.“Without treatment, doctors say, he may soon die. If we get the drug, his body will be slowly cleansed of the toxins,” Elena continued. “He may be able to walk again, and play, and enjoy life, like other kids.”Hunter syndrome cannot be cured, yet patients can live well into their 20s or even 30s, if provided with a drug that helps their bodies get rid of toxins. The annual cost for Volodya was almost US $800,000 – beyond comprehension for Elena whose husband left the family at the first signs of the disease.She petitioned all sorts of organizations and was about to sue the local authorities when in April they finally agreed to provide the money for the drug. Back then, that piece of paper seemed to be Volodya's license to life.“When I got this letter, I was so hopeful… It meant that my child would live,” the mother explains. “I couldn’t stop hugging and kissing Volodya, telling him that at last there is the money and that his life would be saved.”They waited weeks, then months. In early June, Volodya's health took a turn for the worst and he died, never having seen the promised drug.Most parents agree that losing a child is the worst thing that can happen to a parent. But Elena says it is not. The worst thing for her is to live the rest of her life knowing that her child could have been saved, that the treatment was there and this exorbitant sum of money was found, yet, due to red tape or administrative procedures, her son Volodya was never given a chance.Local health officials say there was absolutely no way to speed things up. The Orel region, where Yelena lives, is an impoverished, mostly agricultural province in central Russia. Volodya's treatment would have accounted for about a quarter of all health subsidies.“The treatment of this boy, in monetary terms, is equivalent to almost all cancer surgeries in our region, and we are talking about thousands of people,” says Aleksey Medvedev, a health commissioner of the Orel Region. “Yet, we still made a decision to allocate this money. But before this could translate into actual ampules with the drug, we needed to conduct some budget restructuring and hold a tender to buy it. Now, these procedures are almost complete, and we expect the drug to be here by the end of June.”While it's already too late to help Volodya, the allocated money may save another little boy. Just 30 kilometers to the south lives seven-year-old Petya who was also diagnosed with Hunter syndrome. Like Volodya at his age, he is a ball of energy and he also likes cats. And like Volodya, the disease is already taking its toll on his health.The build-up of toxin in his fingers makes it difficult for him to write. His internal organs are enlarged. Yet, he still has a few years before the damage becomes irreparable. His parents believe, to save their son, the state has to step in.“No single family can deal with this disease on its own,” Petya’s father Vladimir Ryabinin explains. “The cost of the drug is simply unreal. The local authorities often refuse to cover the costs. That’s why I think the state has to help. They are children after all, and any country should take care of its children.”Out of about 250 children with Hunter syndrome in Russia, less than half are receiving medical treatment. It is a zip code lottery, available in rich areas like Moscow or Novosibirsk and almost unimaginable in poorer towns. And that is despite the fact that, when it comes to their citizenship, they are all supposed to be on the same team.