Scientists revive giant virus from 30,000-year-old Siberian permafrost

French and Russian researchers have revived a 30,000-year-old living virus from deep below the frozen Siberian tundra, which they say is the largest ever discovered. It targets amoebae, but hints that other ancient viruses could be in the Earth's soil.

The giant virus was discovered by a group of scientists led by Jean-Michel Claverie and Chantal Abergel, a husband-and-wife duo at Aix-Marseille University in France.

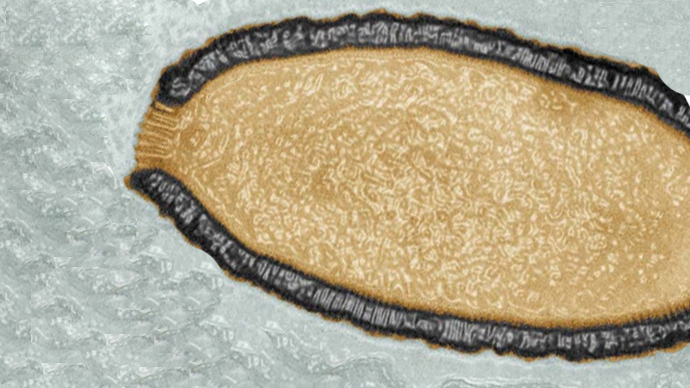

The contagion, which has been dubbed Pithovirus sibericum due to its oddly long and narrow shape, infects amoebae and presents no threat to humans, Nature scientific journal reported.

The Greek word “pithos” represents a large container used by the ancient Greeks to store wine and food. “We’re French, so we had to put wine in the story,” said the researchers, who published their results in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Scientists have long known that viruses can survive for thousands of years. For example, latent smallpox virus genes were discovered in 400-year-old mummies.

However, the Siberian virus is not latent. It has shown to be able to infect host cells and replicate.

Using permafrost samples extracted from a Siberian riverbank and provided by the Russian Academy of Sciences, the researchers fished for giant viruses with amoebae to see if the ancient contagion could infect them.

After it was discovered that the amoebae were dying off, the scientists were surprised to find that the viruses were multiplying inside the amoebae.

The pithovirus is certainly unique in its characteristics, measuring 1.5 micrometers long and 25 percent larger than any virus previously found.

"Sixty percent of its gene content doesn't resemble anything on earth," Abergel said.

“This guy is 150 times less compacted than any bacteriophage (viruses that infect bacteria). We don’t understand anything anymore!” Claverie said.

Though the giant virus presents a threat only to amoebae, the researchers suggest that while the Earth's ice melts, the soil may hold other viruses harmful to humans or animals. “At the moment, there’s no reason to believe they [are not] also resistant for a long time under the same conditions,” Claverie added.

Claverie pointed to the risks associated with a thawing tundra, which could attract people to the region.

“There will be people where there were no people before, and those people are going to manipulate and disturb those [soil] layers that have not been disturbed for a million years.”

As for how giant viruses evolved, Claverie admitted, “at the moment, your guess is as good as ours.”