Launched in 1977, the NASA Voyager spacecraft recently entered a mysterious zone located between our solar system and the great frontier of space beyond. Physicists are puzzled since their theories didn’t predict anything like it.

As Voyager-1 whizzes through this unchartered frontier, a place

so distant that charged particles from the sun have virtually

disappeared, astronomers are struggling to make sense of the

steady stream of data being returned to Earth.

Astronomers initially believed Voyager-1, which is about 11

billion miles from earth, had reached interstellar space on

August 25, 2012, becoming the first man-made vehicle to breach

the threshold of our solar system. But feedback from the

spacecraft, which showed that the sun’s magnetic field was still

exerting its influence on the probe, quickly cooled that theory.

As it turns out, the craft is still in the sun’s house, so to

speak, standing on the porch with the endless galaxy beyond.

If Voyager-1 had really entered interstellar space, physicists

say, the direction of the magnetic field would be different.

"If you looked at the cosmic ray and energetic particle data

in isolation, you might think Voyager had reached interstellar

space,” said Ed Stone, Voyager project scientist at the

California Institute of Technology in Pasadena, “but the team

feels Voyager-1 has not yet gotten there because we are still

within the domain of the sun's magnetic field."

Stone first explained the discovery of this unexpected zone

during a lecture at the American Geophysical Union last year. A

collection of papers published on Thursday in the journal Science

put the findings into perspective.

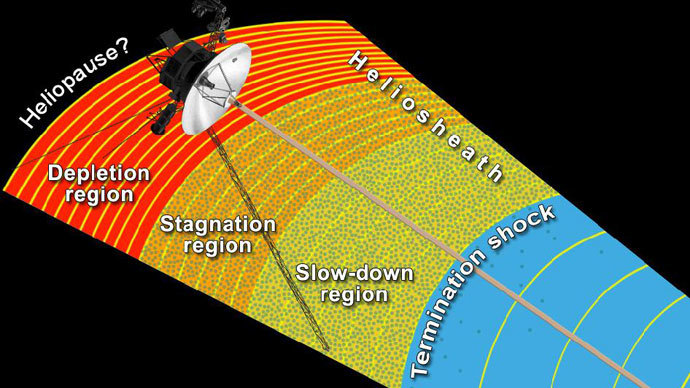

In 2004, Voyager-1 reached a highly charged region known as the

heliosphere, a bubble-shaped region surrounding the solar system

where particles move in all directions due to solar winds. It was

anticipated this would be the final leg of the trip before the

spacecraft broke free of our solar system and entered

interstellar space.

"You can never exclude a really peculiar coincidence, but this

was very strong evidence that we're still in the

heliosphere,” Voyager scientist Leonard Burlaga, the lead

author of one of the papers, based at NASA's Goddard Space Flight

Center, told Reuters.

Measuring the size of the heliosphere is also part of the Voyager

mission.

Scientists believe that Voyager-1 journeyed into something of a

magnetic boundary zone, where particles from inside and outside

the solar system interact, but where the gravitational pull of

the sun remains dominant.

"A day made such a difference in this region with the magnetic

field suddenly doubling and becoming extraordinarily smooth,"

said Burlaga, "But since there was no significant change in

the magnetic field direction, we're still observing the field

lines originating at the sun."

NASA has got a lot of mileage out of Voyager-1 and its sister

spacecraft Voyager-2, which were launched 36 years ago to collect

data on Jupiter and Saturn and their respective moons. After

completing their mission, the vehicles were sent hurtling toward

interstellar space for what will certainly be their last mission.

Voyager-1 is heading in the direction of a star known to

astronomers as AC +793888, but it will only get to within two

light-years (one light year equals the distance that light

travels in one year) before its nuclear energy source depletes

itself sometime in the next decade. Voyager-2, meanwhile, is

exiting the solar system from a different direction, and has not

experienced the same phenomena.

"Voyager-2 has seen exactly what the models predicted we would

see, unlike Voyager 1, which didn't," said Stone.

Voyager 1 may be in a unique place where the heliosphere and

interstellar space interconnect, he added.