Scottish Independence: Reflections on a historic campaign

The referendum on Scottish independence will go down in history as a glowing testament to the virtues of the democratic process after it succeeded in capturing the imagination and participation of an entire nation.

The day after the referendum, which recorded a vote for Scotland to remain part of the United Kingdom by 55-45 percent from a voter turnout of 84 percent, was what we call in Scotland a ‘dreich’ day (wet, grey, and gloomy). I found myself outside the Scottish Parliament building in Edinburgh among people who were milling around numb and still in a state of shock over the result amid the international media and press. Many were carrying Scottish Saltire flags and sported Yes badges. It almost felt as if the world had stopped turning, a mood that combined with the weather to create a mournful atmosphere.

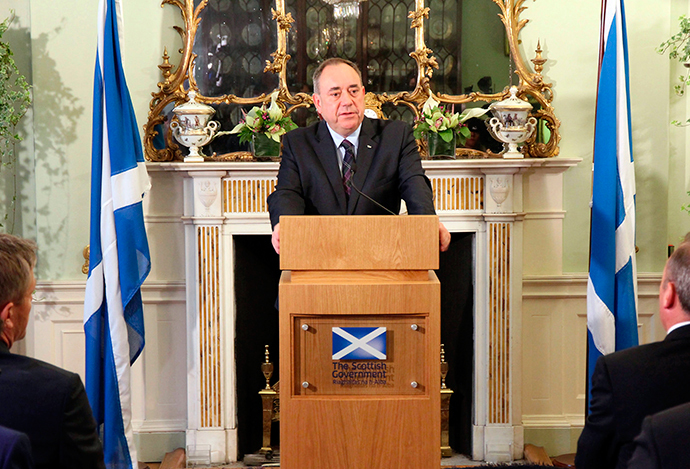

Compounding this was the news that the leader of the Scottish National Party and Yes campaign, Alex Salmond, had decided to resign as leader of the party he had led for two decades. In that time, he had succeeded in dragging the SNP from the margins of the political process where it had resided for decades, almost as a quaint club for people living in the past, to the very heart of Scottish and UK political establishments.

More than this, Alex Salmond had just brought the country closer to the point of independence than any other time since the Act of Union in 1707 gave birth to the United Kingdom. This is why, watching his resignation speech, you could not help feeling for him and his supporters, regardless of your stance on the issue; his grace and dignity in deciding to fall on his sword adding a Shakespearean quality to the end of a chapter in Scottish and British history that no one who lived through it will soon forget.

There are hardly words suitable to describe the immensity of the Yes campaign for Scottish independence. It mobilized thousands of people across Scotland to produce such a groundswell of support for independence it rocked the British establishment to its very foundations. Who could ever have foreseen at the start of the 16-week referendum campaign, when the polls had the No campaign 20 points ahead, that in the final two weeks this mass grassroots mobilization would compel a Conservative Prime Minister and the leaders of the two main opposition Westminster parties to scurry up to Scotland from London in a panic stricken last ditch effort to save the union?

As the day of polling on 18 September approached, the Yes campaign took on the character of a democratic insurgency in parts of Scotland, specifically within poor and low income communities in its former industrial heartlands – those parts of Scotland that had been decimated by the country’s deindustrialization through the Thatcher years and which no government since, Labour or Tory, had seriously attempted to redress. People who had been disenfranchised, disconnected, and alienated from the democratic process for a generation were inspired by a belief in Scottish independence as a new beginning. They saw it as a transformational event that would lift them and their communities out of the mire of poverty and despair in which they had existed for far too long.

All of this hope, belief and passion served to cocoon its adherents from the glaring weaknesses in the SNP and Alex Salmond’s vision for Scottish independence. It meant that regardless of the fact that with the retention of Sterling as the national currency and the monarchy as head of state, or with an independent Scotland joining NATO and the EU and the proposed 3 percent cut in business tax, the reality was that rather than any departure from the status quo, the program put forward by the SNP had status quo stamped all over it.

But the grassroots Yes campaign was not about political programs in the here and now. It was instead a campaign predicated on the future, where idealism fueled a belief in the ability of the Scottish people to forge a new society come what may, no matter the risks or challenges involved. In this it had much in common with the mass grassroots mobilization responsible for propelling Barack Obama into the White House in 2009 as America’s first black president. Hope and change were the mantras of the Obama campaign and they were also front and center in the Yes campaign for Scottish independence. And while hope and change may be hollow words that amount to nothing without a solid plan or program to substantiate them, when inscribed on the banners of tens of thousands of people whose need for hope is elemental, they take on a life of their own.

But in the end the No vote came through. In large part this was because 2 million people out of the 3.6 million who cast a vote were not prepared to take the leap in the dark which, at bottom, is what they were being invited to by the SNP. The economic case for independence had been well and truly lost by polling day, leaving hope and the emotional attachment to the very idea of independence the factors in its favor.

That being said, the key factor in the Yes campaign’s favor was the No campaign. Because just as the Yes campaign was undoubtedly one of the most vibrant, broad, and effective ever waged in Scottish and British political history, the No campaign will go down as one of the most limp, narrow and inept. The Better Together campaign was led by former Labour Chancellor Alistair Darling, a man who possesses all the charisma of a plank of wood. It was made up of an unholy alliance of Labour, the Tories and Lib Dems. It was so bad that at times you almost felt it was being secretly organized by the Yes campaign.

The sight of a technocratic former New Labour minister, like Darling, telling the Scottish people why independence was a bad idea was hard to bear. And he was abetted in the endeavor by a Tory Prime Minister, David Cameron, whose contempt for the poor and working class people, not only in Scotland but throughout the United Kingdom, is evident in his government’s austerity agenda.

Indeed, as polling day approached, with the polls neck and neck, it was left to Respect MP George Galloway, a man expelled from the Labour Party in 2003 over his opposition to the war in Iraq, to make a progressive case for Scotland remaining in the Union. This he did like a man on fire, touring working class areas of Scotland to exhort, as only he can, people to reject Scottish nationalism on the basis that working people throughout the UK have the same interests, struggles, and needs in common regardless of where they live or whether they are Scottish, English, Welsh, or Irish.

George Galloway’s considerable efforts were augmented by former Prime Minister Gordon Brown, who entered the battle with just ten days left to mount an intervention which many commentators have adjudged saved the day for the No campaign. He was the architect of the deal, known as the pledge, which all the unionist parties and David Cameron agreed to, promising more powers for the devolved Scottish Parliament in the event of a No vote on September 18.

However, with the result of the most historic election in UK political history just days old, this ‘pledge’ is already unraveling as Cameron, under pressure from his own party, refuses to sign up to more powers for Scotland without more powers being granted to Wales, England, and Northern Ireland at the same time.

Rather than put the issue of Scottish independence to bed for a generation, as now former SNP leader Alex Salmond declared the referendum would, it has kicked over a constitutional hornet’s nest, resulting in a political crisis that seems set to run and run.

The question of independence for Scotland is far from being settled. Not by a long chalk.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.