Old man giver: Paul Robeson’s altruism shouldn’t be forgotten

British Oscar-winning director Steve McQueen is to make a biopic of Paul Robeson, the black American entertainer whose commitment to the common man’s plight, regardless of race, creed or nationality, left behind a legacy that will never be surpassed.

The early years

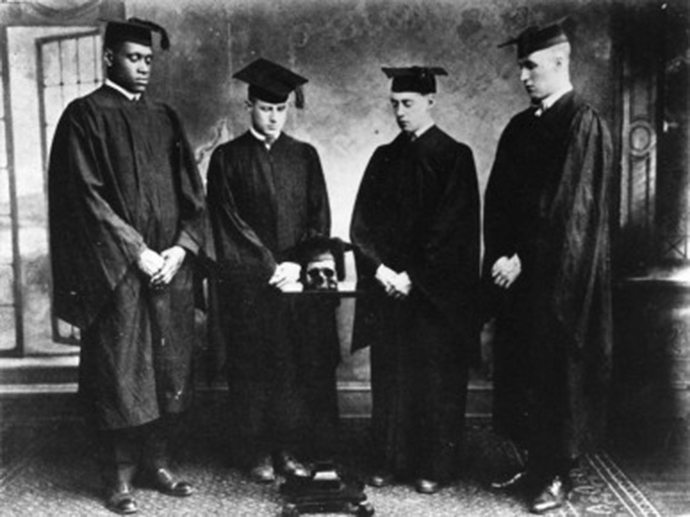

One of my most treasured possessions is a book of the writings and speeches of Paul Robeson. It charts his remarkable life from the post WWI years, when this son of an escaped slave first came to prominence as a student at the prestigious Rutgers University, where he excelled in college football as the only black player on the team, and first demonstrated his prodigious talent as an actor and singer.

It moves on to the 1920s, when after a brief flirtation with a law career Robeson entered the world of show business, finding international fame on Broadway by the end of that decade. The 1930s he mostly spent in London, where he embarked on a career in movies, playing a succession of African characters that in their depiction of servility and racial stereotyping he would later consider an insult to his people. It is here in England in the thirties where he experiences the political, racial, and social awakening that would define the rest of his life and legacy. In particular he forges an undying bond and affinity with the Welsh miners, identifying with their struggle and proud musical cultural tradition, one he associated with his own people in the United States.

Solidarity with the Soviet Union

By the 1940s Paul Robeson was a passionate anti-fascist and anti-colonialist, who having visited the Soviet Union returned an unapologetic supporter and sympathizer with the socialist state. “During the 1934-1938 period I visited the Soviet Union many times and decided to send my boy there to school. There I found the real solution of the minority and racial problem, a very simple solution – complete equality for all men of whatever race,” he wrote.

What’s remarkable here is that the period Robeson describes in the letter is referred to by anti-Soviet historians as the Great Terror, when it is commonly asserted that millions were being arrested and either executed or sent to the gulag by Stalin. Robeson was therefore accused of glossing over this hugely convulsive period in the Soviet Union’s history. Yet Robeson felt compelled to announce during a 1935 visit to the country that he “was not prepared for the happiness I see on every face in Moscow…It is obvious that there is no terror here, that all the masses of every race are contented and support their government.”

The singer and by now political activist had visited Spain during the Civil War, where he toured the country singing to the anti-fascist Republican troops and volunteers to raise their morale. Like many within the artistic community in the United States and throughout Europe, Robeson considered fascism to be the common enemy of mankind. Indeed, during the Second World War he extended himself in touring war plants and factories throughout the US giving concerts and speeches in support of the war effort. He combined this with regular appearances onstage, winning rave notices for his portrayal of Shakespeare’s Othello in particular. Touring with the play, he refused to appear in Southern states in venues where segregation was in force. In a 1942 speech to a mixed audience of blacks and whites in New Orleans, he said, “Nothing the future brings can defeat a people who have come through three hundred years of slavery and humiliation and privation with heads high and eyes clear and straight.”

Robeson was tireless in working to unite workers across the racial divide, reminding delegates at the annual convention of the International Longshoreman’s and Warehouseman’s Union in 1945 of “the necessity of complete unity of all groups in our country.”

Demonization

After the Second World War, he found himself under attack from the political and media establishment in the United States for his refusal to renege on his support and solidarity with the Soviet Union. If anything he raised his voice even louder when it came to articulating his refusal to bow to the huge pressure to conform to the new wave of anti-Soviet hysteria as the Cold War got underway. His appearance at the 1949 Paris Peace Conference resulted in a firestorm of criticism in the US press after giving a speech in which he was reported to have said, “It is unthinkable that American Negros would go to war on behalf of those who have oppressed us for generations against the Soviet Union which in one generation has lifted our people to full human dignity.”

Despite claiming that his words were distorted by the American press, he was hung out to dry, depicted as a traitor and a dangerous subversive. When a reporter asked him about a story claiming that during a recent visit to Moscow he said that he loved Russia more than any other country, he replied, “What I said was that I love the America of which I am a part. I don’t love the America of Wall Street. I love the America of the working class. I love the working class of England and France and other countries. And I very deeply love the people’s democracies in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union…They are fighting for my people and for the white working people of the world.”

Refuses to yield

It was now that Robeson was deserted and abandoned by former friends and allies in his home country as a campaign of demonization succeeded in uniting right and left against him. He was a major target of the McCarthyite anti-Communist witch-hunts of the 1950s. But even so he remained defiant, “The big lie is the fairy tale that the American people are somehow threatened by communism,” he wrote in 1954.

In fact rather than slow him down, the pressure he was under merely served to increase his determination to continue to fight for the causes he believed in. He continued to raise his voice and speak throughout the United States in solidarity with workers in a struggle, with poor blacks suffering the degradation and humiliation of racist segregation, in solidarity with the Vietnamese struggle against French colonialism, against apartheid in South Africa, and for peaceful co-existence with the Soviet Union and Eastern bloc.

Increasingly the State Department began taking steps to silence him. In order to prevent him travelling overseas, his passport was revoked. Thereafter scheduled television appearances and concerts were cancelled and over five years from 1950-55 repeated applications for a passport to enable him to travel out of the US to make a living were denied by the US Passport Office. When in 1955 he appealed to the Supreme Court to have his passport reinstated, the Judge presiding over the case implied that one may be issued to him if he agreed to sign a “non-Communist oath.” Robeson refused.

During this period his career as a singer and performer dried up, and with it his income, which plunged from $150,000 to $3,000 per year.

A new appreciation as the struggle continues

Finally, supported by an international and national campaign, Robeson was allowed to leave the US in 1958, embarking on an international itinerary which took him to London then on to Eastern Europe, where he was accorded a hero’s welcome. Appearing at a Miners Gala in Edinburgh, Scotland to celebrate May Day in 1960, he told his audience, “My people were hewers of wood and drawers of water all over the Western world. Today on the continent of my forefathers, we are saying it is time for us to live a new life, time to be free.”

Though the 1960s marked a steady decline in his health, by its end the demonization he had suffered over many years gave way to a new appreciation of his life and convictions. In 1971 his 1958 autobiography, ‘Here I Stand’, was reissued to critical and literary acclaim, and in 1973 a Salute to Paul Robeson concert was held at a sold out Carnegie Hall in New York to celebrate his 75th birthday. Upon his death in January 1976, 5000 people attended his funeral in Harlem.

What to make of such a rich life and how to begin to condense it into a film? Perhaps it is best to begin with its meaning, which in the case of Paul Robeson is surely that it is not what we win or gain that marks a man’s success, but what he is willing to sacrifice for a cause greater than himself.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.