Chances of new alliances clustered around Tokyo as Japan moves towards military normalization

With Japan moving towards military normalization, regional geopolitics in the East and South China Sea might be transformed creating new and unlikely alliances and new power blocs.

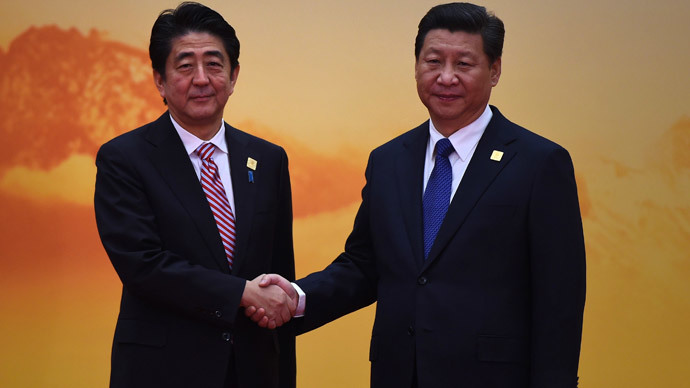

The handshake between Chinese President Xi Jinping and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe at the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) summit in 2014 in Beijing, though awkward, had many to believe that a slow thawing of the relationship between the two countries could be in progress.

In fact, months after the APEC meet China and Japan held talks on setting up of a military hotline to counter any emergency in the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands – a disputed region in the East China Sea administered by Japan but claimed by China who regards it as Chinese territory from before the First Sino-Japanese War.

However, going by the new moves Japan is taking; it is evident that the threat perceptions still remain. The re-elected Abe seems to be drawing closer to a more assertive military stance for Japan than has been the case post World War II.

Japan with a past of war atrocities during World War II has been following a security policy of self-defense only with no right to involve in any collective defense activity with its allies or otherwise.

However with the regional geopolitics changing and an overpowering China, Japan has taken up the path towards ‘military normalization’ by increasing its military budget after decades of modest defense spending and also reinterpreting its right to defend its allies.

This transformed security outlook may change the regional geopolitics creating new and unlikely alliances and power blocs.

Threat Perceptions

Abe showed signs of moving towards the right of defense assertion in 2013 when for the first time in 11 years Japan announced an increase in the country’s defense budget enhancing the efficiency of the Japan Coast Guard (JCG) and the Japan Self-Defense Force (JSDF) by arming it with amphibious capabilities to safeguard its maritime interests.

This year the prime minister inaugurated his return to power with the announcement of a $42 billion military budget - an increase in spending of 2.8 percent - to procure items such as patrol aircraft, early-warning aircraft, stealth fighters, and amphibious vehicles

Putting the defense bracing in context Defense Minister Gen Nakatani said, "The situation around Japan is changing". "The level of defense spending reflects the amount necessary to protect Japan's air, sea and land, and guard the lives and property of our citizens."

What Nakatani could be referring to is China’s aggressively growing military might. Last year it announced boosting itsdefense budget by 12.2 percent (nearly $132 billion) which is more than Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and Vietnam combined.

Reports also have it that Beijing, till now a significant buyer of Russian aircraft, ships and submarines, is getting into building up its own domestic defense production having already launched its first aircraft carrier in 2012.

Additionally China’s home-made fifth-generation stealth fighter and twin-engine J20 are expected to be operational by 2018 (though some experts are skeptical of its capabilities) making an uneasy Tokyo calling for more transparency on the reason for Beijing’s growing defense outlays.

This is evident from the annual defense whitepaper Japan released last year clearly expressing Tokyo’s discomfort with the activities of Chinese ships and aircraft in disputed areas such as the South China and East China Seas, and also tacitly sending messages of some inadvertent consequences should such activities continue unabated.

Japan was responding to the heightened surveillance by China in the East China Sea since 2012 following the Japanese government’s purchase of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands from a private owner, which lead Beijing to place a warship targeting Japanese helicopters and a naval destroyer, and enhancing its Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) to include part of the East China Sea, thus demanding that aircraft flying into its zone identify themselves, reveal flight data, or be prepared for emergency actions.

Robust Pacifism

Last year Abe announced a "reinterpretation" of the Japanese Pacifist Constitution which proclaimed Japan’s armed forces were for domestic self-defense only, and could not participate in any third party defense or offence of its allies or otherwise, not even in UN-backed conflicts, other than as peacekeepers.

The reinterpretation, therefore, marked the end of Japan's self-imposed ban on military assistance to an ally under attack allowing for the overseas deployment of the Japanese military, much to the pleasure of the US which for long had been demanding that Japan gets more ‘involved’ in the security base that Washington has in the region rather just being a mute beneficiary.

This opened up a new chapter in defense cooperation between Japan and its allies - notably the US - with possibilities of Tokyo now free to defend its allies in case of an attack on them – a move which perhaps other than China/North Korea aggressively proliferating its nuclear program would have taken note of.

China’s rise could be making even traditional friends like Australia nervous, evident from the announcement late last year that defense ties between US-Japan-Australia would be deepened further. This could get more formidable with Tokyo taking back its right to collective defense.

New alliances clustered around Japan

Smaller Southeast Asian nations like the Philippines which have readily accepted America’s Asia pivot as a means to counter China, are increasingly getting apprehensive about a possible scale down of military spending by the US precipitating the fear of a more emboldened China.

As Japan increases its military spending and lifts restrictions on its rights to defend its allies, these smaller countries may find a new alternative ally in Japan, thus creating a new alliance system in Asia.

Apart from the US, Japan has many supporters for its military upgrade which includes the Philippines, Vietnam many of whom are already in partnership with Tokyo following Abe’s ‘reinterpretation’ cooperating in military training and aid, joint weapons development, and arms sales.

Tokyo may take this opportunity to build up the security capabilities of China’s opponents through low scale weapons supply for watching over their maritime security.

Reportedly Taiwan, earlier under Japanese colonization and today sharing China’s territorial claims, seems to be ready to forget the past with high profile officials stating that Japan’s move to embrace collective defense will only make the region safer.

While there indeed is a possibility of newer kind of alliances clustered around Japan, China may also group up with Tokyo’s arch rival South Korea with which Beijing already has a burgeoning relationship especially in terms of trade and a shared history of colonial past under Japan – a memory China always exploits to widen the rift between the Japanese – South Korean relationship.

An example of this is the memorial hall constructed by China - at the proposal of South Korean President Park Geun-hye during her Beijing visit in 2013 – commemorating the Korean national Ahn Jung-geun who had assassinated Japanese Governor General of Korea Hirobumi Ito on Oct. 26, 1909 – who Japan calls a ‘terrorist’. The memorial is situated in the Chinese city of Harbin where the assassination took place.

Even while responding to Abe’s reinterpretation of Japan’s Pacifism, China and South Korea were together in condemning the decision. Beijing stated, "China opposes the Japanese fabricating the China threat to promote its domestic political agenda," adding, "We demand that Japan respect the reasonable security concerns of its Asian neighbors and prudently handle the relevant matter."

“Threat perceptions” may lead to a greater arms race in the region especially between China and Japan with smaller nations being compelled to take sides. There’s clearly a vacuum created in the region for a balancing factor that can deter any major collision in the region especially in the East China Sea. Obviously the US with its own problems in the Middle East and Russia cannot play this role.

Can Indonesia’s Jokowi, Japan’s major trading partner and a known solution seeker in the South China Sea dispute, be the one that can facilitate talks between competing states including China, Taiwan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Brunei and Malaysia – replicate its role in East China Sea?

After all it has been a long advocate of Code of Conduct in the South China Sea which proved its mettle as a mediator by closing a long time maritime boundary dispute with the Philippines.

Indonesia could soon get drawn into the dispute with China’s rapid advance towards the region around the Natuna Islands situated in Indonesia’s Riau Islands province that constitute the southern limit of the South China Sea which Jakarta considers its exclusive economic zone (EEZ). Quite obviously it will be impossible for Jakarta to stand as a neutral middleman.

So how peacekeeping is sought in the region by all the parties involved – amidst the major powers asserting their defense postures - is a major thing to watch out for as the year unfolds.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.