Muslim women, Israeli settlers and the struggle for Al-Aqsa Mosque

Israeli settlers come to Al-Aqsa every day, but Palestinians don’t like it. They think the Israelis want to take the mosque away from the Muslims, as they did with the Ibrahim Mosque in Hebron. Crying ‘Allahu Akbar’ is their only weapon.

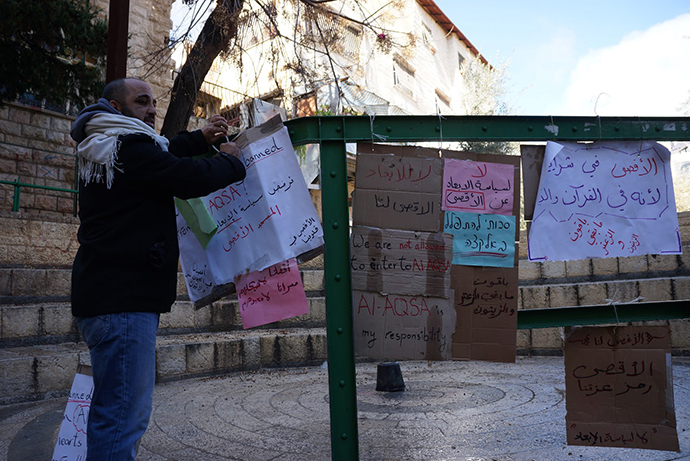

Several women put up posters calling for their shrine’s protection in a small yard of Jerusalem’s Old City near the gates of Al-Aqsa. They come here early in the morning. They eat sandwiches for lunch. They are forbidden to enter Al-Aqsa. At 11.30 am they go to the closest army checkpoint, spread their prayer mats, perform salat (ritualistic prayer in Islam) and leave to return the next morning.

Latife Abdellatif, a Palestinian woman resident in Jerusalem, is 24. She is a Maths teacher and has been coming to Al-Aqsa to pray since her childhood. In November, she was banned by Israeli security officials from approaching the mosque for saying ‘Allahu Akbar’ when approaching Israeli settlers in Al-Aqsa.

Latife is one of the Muslim women protesting against Israeli settlers’ flocking to the Al-Aqsa mosque.

Palestinians establish different groups and foundations to protect Al-Aqsa, which are then shut down by Israeli authorities, one by one, under various pretexts.

Latife received a three-month ban; for some this is six months. Sometimes, Israeli policemen confiscate IDs, which are vital for Palestinian women in Jerusalem. Others have been sentenced to house arrest.

What’s behind the Al-Aqsa protests?

There are two mosques in this compound in Jerusalem’s Old City – the Al-Aqsa Mosque and the Dome of the Rock. These mosques are controlled and managed by the Jerusalem Islamic Waqf, an Islamic trust. But access to the Al-Aqsa compound is controlled by Israeli army units, which are also allowed to enter and search the premises daily, and to arrest Palestinians. You don’t find any Palestinian police units here.

This conflict is not merely religious; it also involves politicians, historians and even archeologists.

Al-Aqsa is the third holiest site for Muslims following Mecca and Medina. Muslims believe this is where Christ’s Second Coming and the Final Judgment will occur.

Jews believe the Dome of the Rock is built on the site of Solomon’s temple. They are certain the Temple Mount is the site where Abraham was going to sacrifice his firstborn son Isaac. They agree the Final Judgment will happen here, but they believe it will only be for the Jews following the coming of the Messiah.

Muslims don’t agree with the name ‘the Temple Mount’ because they don’t believe this is the site of the Jewish temple. They believe that Abraham’s firstborn son was Ismael, not Isaac, and that Abraham was supposed to sacrifice him not in Jerusalem, but in Mecca. These are facts known by any person practicing Islam and preparing for the Hajj.

Muslims deny all Jewish claims to the Al-Aqsa compound. They believe the state of Israel is simply using fundamentalists to seize yet another piece of land.

Muslims and many scientists, including Israeli archeologists and Israel’s leftists, say that despite massive excavation work conducted here by Israelites, they were unable to uncover a single artifact proving that Solomon’s temple was sited here, or any archeological proof that Jews used to live in the Holy Land before the time of King Herod.

The idea of the protest

The idea of the protest is as follows: as soon as the women see Israeli settlers or their guards walking around the mosque, they start chanting “Allahu Akbar.” The Israeli army and security services see to it that settlers come here without their prayer paraphernalia. They also make sure women don’t approach settlers. They photograph and videotape these women while the latter do their best to hide their faces, because as soon as they are identified they will be banned from entering the area.

Men also used to take part in the protests in the summer. But they received much harsher treatment: some were arrested, others beaten up. In October, the Israeli authorities banned men under 50 and women from entering the compound. The latter started using their voices to protest.

This ideological and religious standoff has been going on for almost six months, but it has been particularly fierce since November.

The schedule of the protest

The Mughrabi Gate is open from 7.30 am, Sunday through Thursday for Jews, Christians and tourists to visit the sacred mosque.

Muslims have a few other gates open to them. If a Muslim goes to the mosque with a non-Muslim friend, they cannot use the same gate.

Only Muslims are allowed to enter on Friday and Saturday. And only they are allowed inside the mosque. The restriction was imposed after an incident in 1969, when an Australian from a fundamentalist Christian church set Al-Aqsa on fire.

Israeli soldiers check all the rooms inside the mosques every evening. This is the only mosque in the world where pilgrims aren’t allowed to spend the night.

Groups of settlers come here every day (except Friday and Saturday) from early morning. They take their shoes off and walk around the Dome of the Rock because they think it’s where the Jewish temple stood before the Romans destroyed it in the 1st century AD.

Muslims think that settlers’ visits have been intentionally provocative over the past six months.

They were particularly outraged when the authorities closed the compound for people under 50 during the month of Ramadan, and even more disturbed when settlers brought in wine and started drinking it. From time to time, Muslims aren’t even allowed to approach the mosque.

In 2000, future prime minister Ariel Sharon came to Al-Aqsa to pray together with settlers, which started a Palestinian uprising.

Muslims say that settlers’ rituals and attempts to pray are all part of a political plan to seize this sacrosanct Muslim holy place, as has been done with many other mosques in the past. Israel has complete control over the mosque outside Bethlehem where Rachel is buried and the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron (Al-Khalil). There is also a campaign under way to gain control of the mosque in Nablus, the site of Joseph’s burial.

Why women?

“Women opened their eyes. There are a lot of us. When they ban some of us, others come instead,” Latife says.

She is outraged that the Israeli army prevents them from saying “Allahu Akbar” on mosque grounds. These are the first words of adhan, the call for prayer, which Israel has made numerous attempts to ban or mute.

“These words mean ‘God is great’. Why is saying them punishable? What’s next? They have already forbidden men under 50 to attend the mosque. They banned women from coming here,” Latife says.

She thinks when their IDs are confiscated at the entrance, it’s a sign of discrimination against women. They rarely give IDs back and this makes life difficult for the women, because without ID they can be arrested.

“If my brother and I go to a prayer on Friday, they’ll take only my ID,” Latife says.

She says it’s an outrage that women are persecuted by the police for the expression of their faith.

“It has happened many times: I walk up to the security guards at the gate, and they already know my name and my address. Is that a threat? Are they showing us that they know everything about us?” she asks.

“We come here every day and sit in front of the entrance. Nothing will stop me from doing so. They think we are afraid of them, but we are not,” Latife says.

Latife’s father owns a book shop. When he was young he also took part in the resistance, which landed him in an Israeli prison for 13 years. Latife’s mother worked as a secretary in the Orient House, and her brother is an architect and an IT specialist.

“Our parents try to stop us, since they only have two children, my brother and me. But young people don’t want to put up with this anymore,” she says. “In the course of five years, they forbade 50 women to come to the mosque. It’s against the law. All women who come to protest got beaten or arrested.”

She stresses that women try to avoid signing papers saying they are banned from the mosque, although this has consequences.

“If you don’t sign, you’ll be sent to a prison in Ramle, near Tel Aviv. They’ll pass a sentence there and determine the duration of the ban,” Latife explains.

Organized protests against the settlers attending the mosque unchecked started in 2011.

Latife has been coming to Al-Aqsa to pray since she was little and she fails to understand on what grounds this right was taken away from her.

Why Muslims are against settlers praying in Al-Aqsa

“The settlers pray here and drink wine. They’ve done it two or three times without suffering any consequences. The law is not the same for everyone. The army is always on their side,” Latife says, bringing up the Second Intifada that began after Ariel Sharon visited Al-Aqsa in 2000. After these events, the settlers were forbidden to attend for a while, but that’s history and they are there again.

“We believe that Al-Aqsa is for Muslims and that the second coming of Jesus will happen in Jerusalem. I’m not against any religion. Prophet Muhammad got along with the Jews. We understand that there are different religious tenets, but we are against the settlers’ plan to demolish Al-Aqsa and build a temple of Solomon in its place,” Latife says.

She points out that no such problems exist between Muslims and Christians.

“During the 51-day war the Christians living in Gaza opened the doors of their churches to Muslims, so that they could pray there, as many mosques were destroyed,” Latife says.

She also talks about a Palestinian Christian who walks the streets during Ramadan to remind Muslims about iftar (the evening meal when Muslims end their daily Ramadan fast at sunset).

“There are many stories like that. The keys to the Church of the Resurrection in Jerusalem have been kept by Muslim custodians for centuries,” Latife says.

She resents such intrusion into Muslim holy places. “Muslims have always been considerate towards other religions. For example, Caliph Uthman purposefully didn’t pray in the Church of the Resurrection when he came to Jerusalem, so that it wouldn’t get turned into a mosque,” Latife says.

She thinks the settlers deliberately come to the mosque to pray, aiming to seize this place later. “The settlers take their shoes off, bow to the Dome of the Rock and don’t turn their backs on it even when they are leaving, because they believe their temple was there.”

“We’re not against them because they are Jewish, we are against them because they are settlers and they take our land, our houses and they want to take Al-Aqsa, too,” Latife says.

According to the young Maths teacher, Muslims aren’t opposed to tourists visiting the mosque, because they don’t pray and don’t want to seize it.

“Just now one of the officials from the Al-Aqsa administration responsible for public relations was arrested,” Latife says, looking through the news on her phone.

“We’re against throwing stones. It doesn’t change anything, only exacerbates the situation. Our protest is a peaceful one,” she explains.

The women walk up to the security post. They spread their prayer rugs and pray. American tourists led by a guide pass by, they exchange a few remarks with the soldiers and take pictures with them. The guide, either talking to himself or to the Muslim women, crisply explains that the Temple Mount is the mountain of the Third Temple. The tourists leave with him.

How does a Christian woman get to Al-Aqsa?

In order to get to the Mughrabi Bridge, you have to go through a checkpoint with a metal detector, show the contents of your purse and walk along the Wailing Wall, then go through another checkpoint. Soldiers ask to see my passport, inspect my purse once again and look askance at the scarf on my head: “You’re not a Muslim? You’re a Christian? OK, you can go. You don’t have a knife, do you?”

The ugly wooden bridge starts here and from it you can see Jews praying at the wall.

And finally there’s the Mughrabi Gate.

On the temple-square in front of Al-Aqsa, men and women are sitting in a circle, reading the Quran. Some elderly men are dotted about here and there. They all wear a keffiyeh. A temple attendant is feeding some fat cats.

Israeli soldiers are everywhere, patrolling the area, communicating on their walkie-talkies. There are groups of tourists with tour guides telling them stories about the mosque in low voices. The signs indicating visit hours for the tourists are so old half the words are worn away. They have been here since 1969.

I hear a faint sound of women chanting “Allahu Akbar” somewhere in the distance and it gets louder.

I come closer. A group of young women covering their faces with veils passes me in a hurry. Right next to them some soldiers appear from nowhere, reporting something loudly on their radios.

People start saying quietly, “Look, settlers, settlers - over there.”

The elders don’t even stir, their eyes glued on the Quran.

Some twenty meters away I see two settlers walking, hands in their pockets. They suddenly change their route – either to avoid the women, or because they have been instructed to do so by the soldiers. They stay away from the mosque. The pair is accompanied by some sort of security detail, also settlers. Every now and then they slow down and exchange some remarks in an undertone. The settlers videotaping the whole procession slowdown in sync.

The young women are nowhere to be seen. I hear they have already been apprehended.

“There are not too many of them today. Settlers come in groups of thirty usually. And the soldiers are always on their side,” says an elderly Palestinian.

The women’s chanting dies down. But now the men’s voices are picking up: “Allahu Akbar.”

Abdallah, a Palestinian resident of Jerusalem, who is banned by the age restriction from visiting Al-Aqsa, explains: “When we say “Allahu Akbar” we remind ourselves of the presence of the Almighty in our lives to encourage each other when we are in distress or scared, and when we need to be reminded of what really matters. These words are not meant to threaten the others. But somehow they do feel threatened by them.”

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.