This week US relations with Saudi Arabia cool down, while heating up with Russia and Iran. Is the US considering a sweeping change to foreign policy?

Saudi King Salman chose not to attend a joint US-Gulf State meeting this week set to deal with the possibility of giving Gulf States a missile defense system to ward off a nuclear-powered Iran. Reading between the lines that means two things: 1) the US would like to sell the Gulf States some more military hardware which is nothing new, and 2) the US is willing to consider the possibility of Iran acquiring nuclear weapons, which definitely is. Saudi Arabia and Israel are not pleased with this development, preferring the more straightforward ‘kill ‘em all’ approach vis-à-vis Iran. In fact, it’s fair to say, that both nations are going ballistic (no pun intended) over the US’s warming relations with Iran.

So at first glance the US has little to gain from entertaining the possibility of increased Iranian military power. The allies are ticked off, and Iran’s status as a dangerous rogue state is such an article of faith to most Americans that warming up to them can hardly be said to score the Obama administration any points domestically.

So why is the US going down this path at all?

Why Iran?

Why now?

Great Satan and the Axis of Evil

To fully appreciate the issues here, let’s briefly recap how things stand.

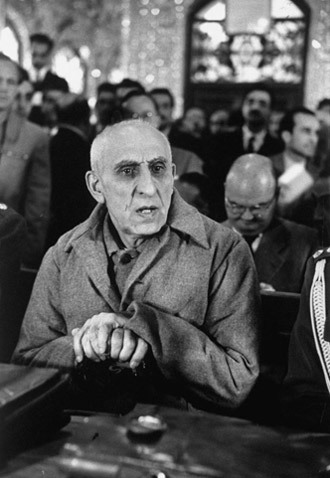

To say that Iran and the West have a long history of acrimony is putting things mildly. It began in the early 1900s, when a British company known as the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (and much later as British Petroleum) set up shop in Iran. Acting with the blessing of both the British and Iranian governments, Anglo-Iranian Oil controlled pretty much all of the oil in Iran, which is, as I’m sure anyone would admit, a lot of oil. For a few decades all went peachy, except for the fact that AIOC creamed off most of the profits and grossly underpaid its workers. In order to deal with this issue Iranian Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh decided to nationalize AIOC in 1951.

All went awry, however, since AIOC had an extremely cozy relationship with the British government, which tried everything in its power to prevent AIOC losing such a profitable gig. This included taking Iran to the International Court of Justice; pressuring other countries not to buy Iranian oil and blockading Iranian ports. It all made everyone pretty miserable, but failed to have the desired effect. Out of luck and out of Iranian oil, the UK asked their buddies in the US to pitch in. The CIA obliged, organizing a slick take-down job on Mosaddegh and the AIOC was back in business in Iran, although the price of CIA cooperation meant that it now had to share some of the oil concessions with American and other European companies.

But Mosaddegh hadn’t acted on a whim when he attempted to deal with distributing Iran’s oil revenues. Severe inequalities existed in Iran, and refusing to reform only kicked the can down the road.

No one else really noticed this, though, because the US and UK had got the oil back and they got on famously with Iran’s constitutional monarch Shah Reza Pahlavi, a very Westernized dude who made all the right noises. One of the more interesting decisions the Shah made – and we shall return to this – was, sitting on top of a lake of oil as he was, to start building nuclear power plants in cooperation with the US. At the time, this was sold to the public as far-sighted preparation for when oil ran out, but in hindsight it looks pretty suspicious, especially since the reactors in question were high-enrichment ones, and forty years on, Iran’s still got plenty of oil.

The Shah’s extravagance and generally nasty behavior did little to endear him with his people, and in 1979 he was finally overthrown in the Islamic Revolution led by Ayatollah Khomeini. This set the stage for a whole new round of mutual agitation. The aging and terminally-ill Shah fled to Egypt outraging many of his erstwhile subjects who wanted him to face trial back in Iran. During the unrest, a group of students invaded the US Embassy in Tehran (or, as they called it, The American Spy Den) and took more than 50 American embassy staff hostage. While Iranian leaders like Khomeini did not order the action on the American embassy, they didn’t do very much to stop it, either. It was back to the ICJ for Iran, this time against the USA. Iran barely participated in proceedings before the court, and lost the case.

Although Iran eventually coughed up the hostages, it faced an ever-growing number of sanctions from the US. Ever since the Tehran hostages, it’s been ‘Great Satan’ on one side and ‘Axis of Evil’ on the other, with greater or lesser levels of enthusiasm depending on the times.

Then in 2005 the US began to make some serious noise over Iran’s nuclear program – the nuclear program, that is, they started back when Reza Pahlavi was in the driver’s seat. In particular, the US claimed that Iran was trying to develop a nuclear weapon and that this was so evil – ‘axis of evil’ level evil, in fact – that Iran was back in the crosshairs.

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty

This time, the US case against Iran isn’t, however, really all that strong.

Yes, nuclear weapons are very dangerous and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which regulates this kind of thing, takes the general approach of:

But the NPT is a curious treaty in that it splits its members into two groups – nuclear members and non-nuclear members. Nuclear members are the ones who have nuclear weapons (US, Russia, China, France and UK), and non-nuclear members are the ones who don’t.

Under the NPT, non-nuclear members agree not to make or receive any nuclear weapons, and to negotiate safeguards with the International Atomic Energy Agency to be used to verify whether the non-nuclear state is using nuclear power for peaceful means only. This is the kernel of the issue here, because under the NPT Iran is a non-nuclear state, and the US is accusing it of not fulfilling these obligations, in particular, not cooperating with the International Atomic Energy Agency.

But what tends to slide under the radar here is that states are under absolutely no obligation to be members of the NPT. Even if you do sign up, you can withdraw anytime. That means that if Iran wanted to build nuclear weapons in perfect legality, it would only have to withdraw from the NPT to do so. After all, it’s worked for Israel, India and Pakistan – NPT non-members who all have nukes.

For another thing, the NPT explicitly allows states to use nuclear energy for peaceful purposes. So non-nuclear states can build as many nuclear power stations as they like. And if you’re going to continue letting members use nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, you’ll never be able to absolutely prove beyond any doubt that they don’t have a weapons program hidden somewhere. It’s impossible to prove a negative. That’s why courts operate on the standard of ‘reasonable doubt’.

So, since you can’t prove a negative and anyone operating a nuclear power plant has some capability of future weapons development, the US can keep up the “Iran might be developing a nuke” line indefinitely, ratcheting the pressure up and down according to their own preferences. The fact that everyone else is proliferating to their hearts’ content, but without having to contend with sanctions, indicates that this is not really about nuclear weapons, dangerous as those are; it’s about Iran’s persistence in refusing to be part of US hegemony in the region.

The US has behaved similarly to Cuba, Venezuela, Russia and many others in their turn. It’s part and parcel of the “if you’re not for us, you’re against us” mentality. A useful foreign policy tool, but one that has its limits.

Getting success by hook or by crook

And that’s what makes three recent developments so interesting: 1) that the US agreed to a tentative deal on Iran’s nuclear program which is supposed to take another step forward at the end of June; 2) that US Secretary of State John Kerry went to Russia to discuss, life, the universe, and Iran this week; and 3) that the US is trying to get the Gulf States used to the idea of missile defense from a potentially nuclear-armed Iran as opposed to their preferred solution which is Iran disappearing from the face of the Earth.

That’s a quick turnabout from the never-proven accusations that have been flying over Iran and nukes for the past decade.

So what’s going on?

It looks very much that the Obama administration really does want to ‘pivot to Asia’ and that they have identified Iran as a potential hinge on which that pivoting could well get done.

That would certainly fit in to the bigger picture.

The US has recently been working hard to redraw global boundary lines that were once thought to be carved in stone. Cuba and Iran are legacy problems from the last Cold War; Iraq and Afghanistan are legacy problems from Bush; and Syria, Libya, and Ukraine are legacy problems from thinking that Russia was willing to go along with whatever the US wanted. That’s a lot of problems to have hanging over your head when you’ve got bigger fish to fry. And the US does have a bigger fish to fry: China. Hence the need to pivot.

Odd as this is going to sound, the US has been trying to resolve its various open problems over the last 18 months. They’ve been trying to resolve them the traditional way, of course, which is to shake everyone else by the scruff of their neck until they let go of whatever it is that the US wants. That’s right, the collective frenzy over Ukraine, Syria, Iran’s alleged nuclear program, etc. has been one big effort to resolve things. Purely in the US’s own interests, it goes without saying, but still, resolved.

Threatening and storming about hasn’t worked out yet, though. All of the abovementioned issues continue to fester, and time’s a-ticking. Not to mention, the US knows perfectly well that it can afford to push Russia, but not to the extent that Russia completely throws its lot in with China.

So it’s time for strategy two. It’s time to start trying to cut some deals.

That’s why the US has its feelers out with both Russia and the Gulf States, why it loosened the embargo on Cuba, and why it is being more cooperative with Iran than it has been in a long, long while.

If the US became friendly with Iran, it might provide it with the corner it needs to roll-up the Middle East, because Iran – if it were so minded – could help in stabilizing Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen and even in settling the Israel/Palestine issue. That’s all a potentially enormous victory for the US Democratic Party – Obama looks like a hero, and Hillary gets a push towards being elected. All the other screw-ups of the last six years can be swept under the rug.

It’s too early to say what is going to happen, of course. The US might still decide that the traditional brow-beating of Iran, Russia and anyone else that gets in its way is still the best route for it. Western media has certainly kept news of Kerry’s visit to Russia low-key. And it should also be noted that the entire ‘pivot to Asia’ plan isn’t going so well. It was dealt another blow when the US Senate refused to fast-track TPP on Tuesday.

But be that as it may: sealing a deal with Iran and Russia could be a quick way for the US to mop up a load of headaches. After all, largely thanks to US foreign policy, Iran is one of the few powers left in the Middle East. And thanks to the long antagonistic history, it has a lot of untapped potential. With a young, exploding population, even the Iranian leadership has a certain incentive to play along and let bygones be bygones.

So, trying to grind Russia and/or Iran into submission was, in the world of statecraft, nothing personal. It might have worked. The US might have succeeded in putting so much pressure on Iran that the government fell, or enough other States decided that attacking the country might be a good idea after all. Crashing the ruble and sanctioning Russia may have led Russia to cave on Syria or Ukraine. But that hasn’t happened yet, and the US has a pivot to execute.

So, if you can’t beat them, join them.

It might be tempting to think that that means that the US has been put in its place, but that’s naïve. Pushing hard against Russia, Iran and anyone else has always been about making sure it’s constantly playing to the limits of its power. The US has now gained some valuable information about where those limits in the multipolar world probably are (for now), information that it wouldn’t have had if it hadn’t made such a big push.

But the nation’s become willing to put some cards on the table, and that means the world just got a lot more interesting.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.