As the US Senate debates the Patriot Act this week, we are at a crossroads for civil liberties and protest freedoms around the world.

Remember this?

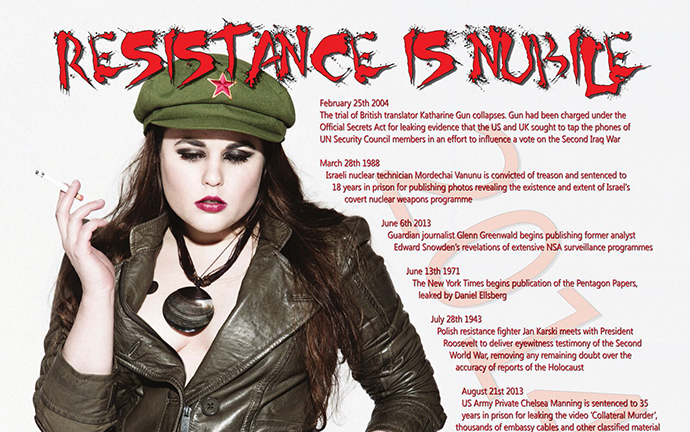

‘Tis but a modest part of my 2014 calendar project to raise money for defending and supporting whistleblowers. As part of that campaign I also did an interview with the show Lorax Live on Anonymous Radio. I’d had to stay up to the wee hours to do this little talk, and I remember checking back a few weeks later to see if it had ever been posted in the online archives. It hadn’t – just the kinds of thing people get behind on, I’d figured at the time – and I promptly forgot about it.

Only months later did I learn that Lorax – real name Adam Bennett – had been arrested and that “the majority of LoraxLive shows are held by Australian Federal Police and have not been placed in the public domain”.

Not only has Lorax been barred from using the internet for political activity, he has been subjected to an ever-rotating number of charges over the past year, relating, among other things, to testing his workplace database (Cancer Support) for Heartbleed vulnerability and defacing an Indonesian government website. The Australian government’s interest in prosecuting for either event is a bit obscure, but perhaps most concerningly of all, efforts to raise funds for Lorax’s legal defense have been thwarted because crowdfunding sites have simply refused to host it.

According to activists, many crowdfunding sites have adopted terms and conditions over recent months that prohibit raising funds for legal defense.

So #gofundme removed page, changed TOS with out notifying :-/ Working to establish new page for support #freeloraxpic.twitter.com/BUfwFfq5ku

— Gemma (@g_advocat) May 12, 2015

That any organization would help to deny someone funding for their legal defense is shocking. Accused murderers, rapists and robbers are all rightly entitled to a fair trial and permitted to pay for that trial as their own resources permit. That same right would be denied to someone merely accused of minor acts of civil disobedience is unconscionable, as it (intentionally or unintentionally) equates contributing to legal defense conducted before a lawfully constituted court with being some kind of accessory after the fact to a crime that no one is even sure yet has been committed. But contributing to legal defense is not the same as paying someone to commit a crime or even endorsing what they may have done – it’s merely recognizing that everyone has the right to a fair trial.

Turns out #youcaring does not care after all. Fundraising page has been pulled down. Third time lucky?

— Gemma (@g_advocat) May 16, 2015

A Kafka-esque labyrinth and anticipatory obedience

Unfortunately, denying hacktivists and whistleblowers access to their supporters is an attempt at isolation that is all-too-common.

For example, after WikiLeaks released the Cablegate documents in 2010, Visa, MasterCard, PayPal and other financial service providers refused to transact donations to the organization, even though there was no reason to believe that WikiLeaks had broken any law. An Icelandic court even found that when it came to the law, the payment providers and not WikiLeaks were in the wrong. Of course, you can get around the blockade by giving earmarked donations to the Wau Holland Foundation, Freedom of the Press Foundation or the Fonds de Défense de la Neutralité du Net (FDNN), which is what I did, but the effects are still chilling.

In December 2010, WikiLeaks received $800,000 in donations, and while that may have naturally tailed off, it would hardly have hit the floor the way it did immediately after the blockade. As politicians repeatedly attempted to link the organization to some kind of criminality or even terrorism, individuals and financial service providers alike got cold feet about donating their money, despite the fact that there was no legal basis for proceeding against any donating individuals or the WikiLeaks organization itself.

This kind of action, where individuals and corporations fall over themselves attempting to ‘obey’ laws that don’t even exist is called ‘vorauseilender Gehorsam’ in German. It means ‘anticipatory obedience’ and it is most commonly used to describe the way that people behaved during the Third Reich. Not only did most people not stand up against the actions they saw going on around them, they tried to outdo each other in how well they could anticipate the kind of behavior the fascist regime would like to see.

It’s bone-chilling to see the return of ‘anticipatory obedience’ in the financial blockade on support to perfectly legal causes.

This financial isolation has been underpinned by the twisted trial procedures and draconian sentences imposed on whistleblowers and hackers.

Jeremy Hammond got 10 years for hacking Stratfor, revealing in the process that Pakistani forces had been aware of bin Laden’s presence in the country for years (recently confirmed by Seymour Hersh), that a secret indictment had been issued vis-à-vis Julian Assange and that Stratfor had done a suspicious amount of research on Venezuela and Hugo Chavez.

Barrett Brown’s case was even stranger. Brown was originally charged with (weakly) threatening an FBI officer, and then with copying an already public link to the leaked Stratfor documents and reposting it in another public forum. While the Stratfor charge was eventually dropped, Brown spent over two years behind bars before he was even sentenced, a year of that before trial even commenced. He was finally convicted of helping “the Stratfor hacker avoid apprehension by creating confusion about his identity” and obstruction of justice, in that he tried to hide his own computer when the authorities raided his mother’s house. Brown was sentenced to five years in prison, and was ordered to pay nearly $900,000 in restitution to Stratfor and other companies. It’s a creative way to punish someone for life, when the laws themselves don’t permit indefinite incarceration. Anticipatory obedience at work.

If Franz Kafka were alive today, he’d be sitting up and taking notes. Of course, some will argue that any lawbreaking needs to be punished, however symbolically, and I can’t disagree.

But compare sentencing and treatment in the hactivism cases to the phone hacking carried out by News Corp company News of the World. That paper of record hired a private investigator to hack into the private phones of many individuals including the phone of a murdered schoolgirl. Not only did they listen to the messages on her phone, they deleted some to make room for more. That’s certainly a lot more in the way of ‘obstruction of justice’ than hiding your own computer in a relative’s home. And News of the World did not carry out these actions for any public interest purposes. They did it purely to gain information with the intention of publishing it for profit.

The maximum sentence handed out here? Eighteen months to former News of the World editor and David Cameron’s Communications Director Andy Coulson. He served just 5 months of that. His boss of bosses, Rupert Murdoch, was subjected to nothing more trying than a ‘hearing’; his stately private jet lifting off unimpeded from a British runway while WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange languished in Britain on bail.

Shooting the messenger

It’s all about control as authorities try to head off any budding re-understanding of access to information in the internet era and it’s always justified with reference to THE THREAT, specifically the threat to security. The argument is that any breach of information could put lives at risk and so must be punished very harshly.

This was the argument used against Chelsea Manning and WikiLeaks regarding the information she released through the Iraq and Afghan War Logs – that doing so would endanger the lives of army personnel and those who assisted them. But what about the fact that the information showed other people – the people in the collateral murder video, for example – not just being‘endangered’ but actually point-blank killed in cold blood?

What about the white hat hacker who demonstrated that he could take control of the plane’s engines from the onboard entertainment system? Granted had I been sitting next to him, I think my reaction would have been something like this

but better him than someone else at a later date, right?

Or what about British seaman William McNeilly who recently revealed the sorry state of security and safety around Britain’s nuclear submarines?

Focusing on these ‘possible’ threats such revelations could pose, instead of the real threats they reveal is, once, again, anticipatory obedience at work.

For those running the show, a minor nuclear accident or plane crash are not high priority items, but any form of budding civil disobedience is and that is why it is instantly pounced on.

When hacktivists today arrange a denial of service attack or alter the content of a website or leak important information to the public, sure they’ve committed a very minor breach of the law. So did Gandhi when he walked to the ocean to make salt. So do environmental protestors when they lie down on railway tracks to prevent nuclear waste transports. So do peace activists that try to prevent aircraft from being used to transport rendition victims through their territory and Irish water protesters who try to prevent water meters from being foisted upon them. Like all of the above, hackers and whistleblowers have been notable for the total lack of violence that has accompanied their actions. In many cases, they are motivated by a desire to protect people from abuse.

There should, of course, be some kind of legal process to deal with these situations. You can’t have everyone deciding to take the law into their own hands. That’s fair enough. But that process should be commensurate with the ‘crime’ committed and the public interest served should be taken into account. Above all, hacktivists and whistleblowers should not virtually be expelled from society as some kind of whipping-boys for the powers that be, and subjected to the anticipatory obedience of corporations willing to go above and beyond what the law even demands in persecuting them.

The only thing, after all, that whistleblowers and hacktivists really threaten is the secrecy and therefore the power of the current political system.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.