Hitler invades Russia: Soviet ambassador Maisky’s view from London

Stalin’s disastrous miscalculation of Hitler led to the shock German invasion of Russia in 1941. In his diaries, published by Israeli-born Oxford historian Prof. Gabriel Gorodetsky, Soviet ambassador to London Ivan Maisky describes receiving the news.

Well into the morning of 22 June, Stalin did not exclude the possibility that Russia was being intimidated into political submission by the Germans. Stalin’s miscalculation hinged on the belief that Hitler would attack only if he succeeded in reaching a peace agreement with Britain. This explains the ominous silence and confusion which engulfed Maisky in the early days of the war. It is indeed most revealing that when Maisky met Eden on the day of the invasion, he was entirely haunted by the likelihood of an imminent Anglo-German peace: “could the Soviet government be assured that our war effort would not slacken?” Maisky urged Churchill to dispel the rumors of peace (which had been so prominent since Hess’s arrival in Britain) in his radio speech to the nation which was scheduled for the evening.

Britain was no better prepared for the new reality of an alliance of sorts. The Ribbentrop– Molotov Pact had entrenched a fatalistic political concept, meticulously cultivated at the Foreign Office, that the Soviet Union was “a potential enemy rather than a potential ally.” Once war became almost a certainty (a mere week before the German attack) the chiefs of staff evaluated that the Wehrmacht would cut through Russia “like a hot knife through butter” within 3–6 weeks, leading to the capture of Moscow. The British Government’s gloomy prognosis of Soviet prospects, which at best afforded Britain a breathing space and allowed her to pursue the peripheral strategy, did not encompass a full-blooded alliance, but rather, as Eden put it, “a rapprochement of some sort ... automatically forced upon us.”

22 June

War!

I was woken at 8am by a telephone call from the embassy. In a breathless, agitated voice, Novikov informed me that Hitler had declared war on the USSR and that German troops had crossed our border at 4am.

I woke up Agniya. There was, of course, no question of going back to sleep. We dressed quickly and went down to hear the nine o’clock news on English radio. Novikov had called for the second time a few minutes earlier: Eden wished to see me at 11.30.

We had a hasty breakfast, listened to the nine o’clock news, which added nothing to what we already knew, and set off for London. In the embassy we encountered a crowd of people, noise, commotion and general excitement. It resembled a disturbed beehive.

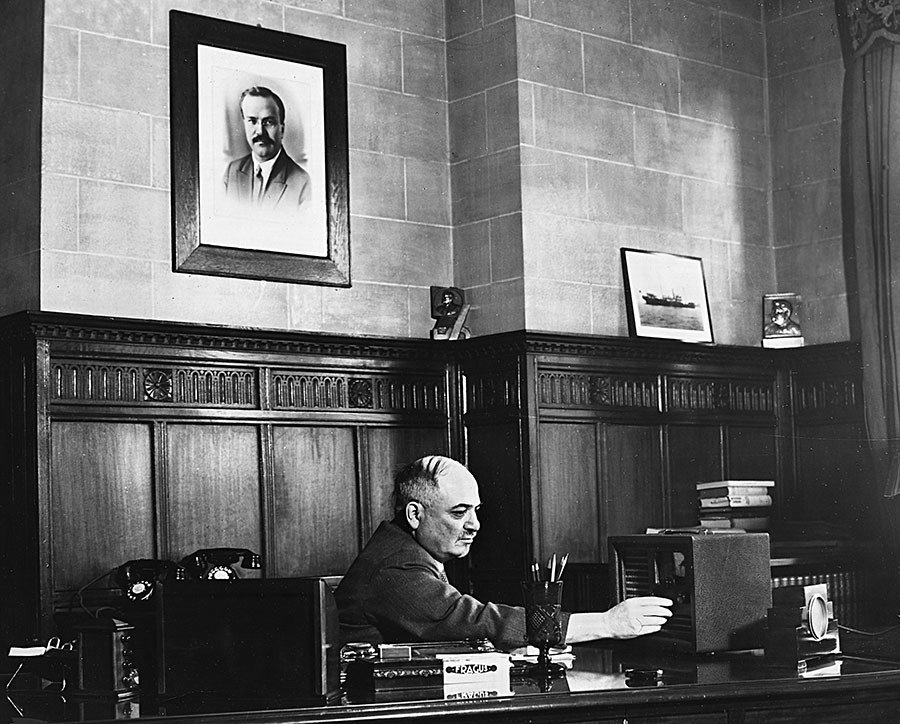

When I was getting into the car to drive to Eden’s office, I was told that Comrade Molotov would be going on the air at 11.30. I asked Eden to postpone our meeting by half an hour so that I could listen to the people’s commissar. Eden willingly agreed. Sitting next to the radio, pencil in hand, I listened to what Comrade Molotov had to say and took down a few notes.

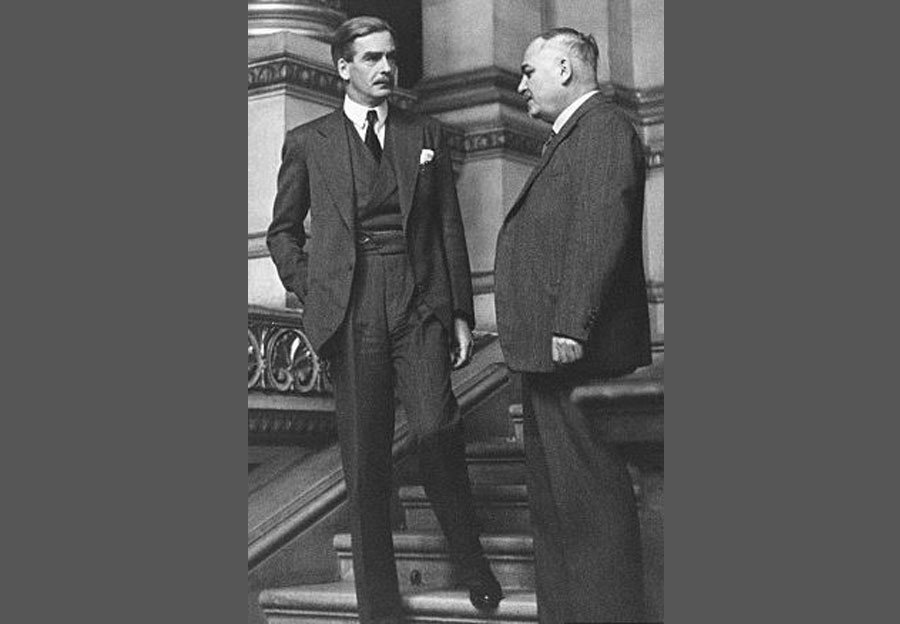

I arrived at the Foreign Office at midday. I was led into Eden’s office. This was without doubt a major, serious and historical moment. One might have been forgiven for thinking, had one closed one’s eyes, that everything should be somehow unusual, solemn and majestic at such a moment. The reality was otherwise. Eden rose from his armchair as usual, and with an affable expression took a few steps towards me. He was wearing a plain grey suit, a plain soft tie, and his left hand had been hastily bound with a white rag of some sort. He must have cut his palm with something. The rag kept sliding off, and Eden kept adjusting it while we talked. Eden’s countenance, his suit, his tie, and especially that white piece of cloth entirely removed from our meeting any trace of the ‘historical’. That modest dose of solemnity which I felt in my heart on crossing the threshold of Eden’s office quite evaporated at the sight of that rag. Everything became rather simple, ordinary and prosaic. This impression was further enhanced when Eden began our conversation by asking me in the most humdrum fashion about the events at the front and the content of Comrade Molotov’s speech. This ‘humdrum’ tone was sustained for our entire meeting. I couldn’t help but recall the sitting of Parliament on 3 September 1939, when Chamberlain informed the House about the outbreak of the war. At the time that sitting also struck me as being too simple and ordinary, lacking the appropriate ‘historical solemnity’. In real life, it seems, everything is far more straightforward than it is in novels and history books.

… At 9pm I listened to Churchill’s broadcast with bated breath. A forceful speech! A fine performance! The prime minister had to play it safe, of course, in all that concerned communism – whether for the sake of America or his own party. But these are mere details. On the whole, Churchill’s speech was bellicose and resolute: no compromises or agreements! War to the bitter end! Precisely what is most needed today.

At the same time, the response came through from Moscow to the question posed by Cripps yesterday: the Soviet Government is prepared to cooperate with England and has no objection to the arrival of British missions in the USSR.

I called Eden and asked him to communicate to Churchill my complete satisfaction with his speech. I also agreed to meet Eden the next morning.

So, it’s war! Is Hitler really seeking his own death?

We did not want war; we did not want it at all. We did all we could to avoid it. But now that German fascism has imposed war on us, we shall give no quarter. We shall fight hard, resolutely, and stubbornly to the end, as befits Bolsheviks. Against German fascism first of all; later, we will see.

Translated by Oliver Ready and Tatiana Sorokina

Read more extracts from Gabriel Gorodetsky’s The Maisky Diaries, Red Ambassador to the Court of St James ’s

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.