London during the Blitz: Soviet ambassador Maisky glimpses East End life

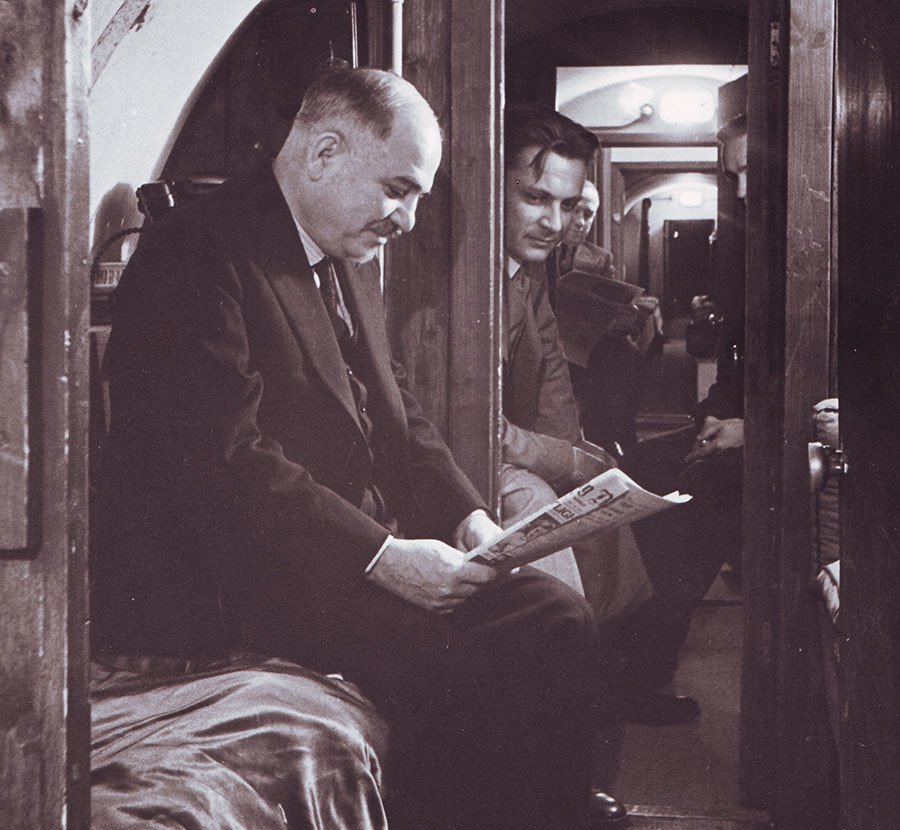

The Soviet ambassador to London Ivan Maisky was offered a glimpse of life for the capital’s poorest during German bombing raids. In his diaries, published by Oxford historian Prof. Gabriel Gorodetsky, Maisky recounts a warm welcome in the East End.

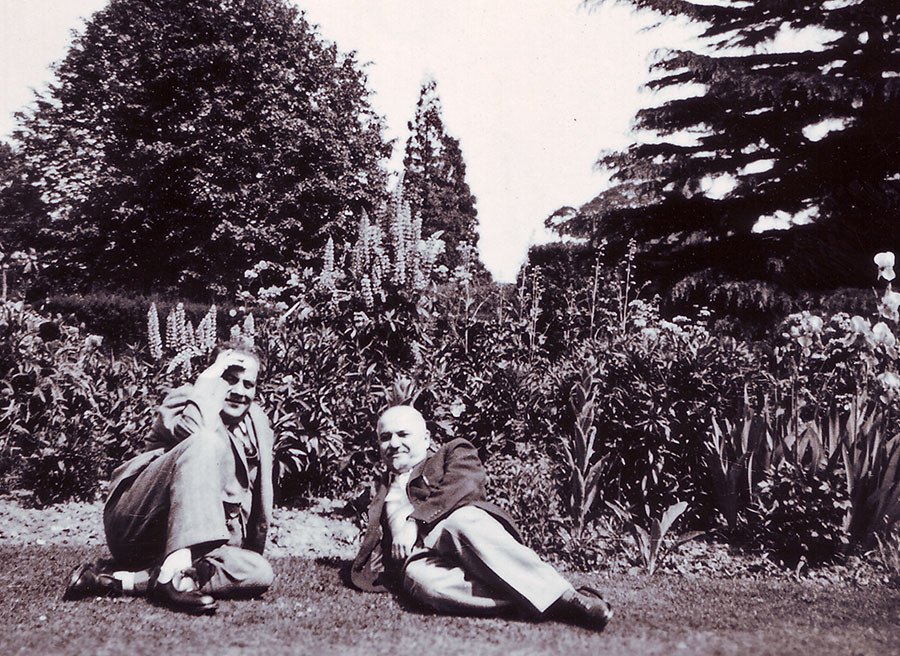

When the Germans started bombing London in September 1940, the families and children of the Soviet personnel at the embassy were evacuated to “a fairly large and comfortable house” in a village near Cheltenham. Agniya, Maisky’s wife, categorically refused to leave London. “Her presence by my side,” recalled Maisky, “was a serious support for me. And for political reasons it was more to our advantage that the British should see the wife of the Soviet Ambassador ‘in the front line,’ not in the rear.” To catch up on their sleep, they tended to spend the weekends out of London at the house of their close friend, Juan Negrín, the former prime minister of the Spanish Republican government. Maisky hinted a couple of times to Molotov that the Germans could perhaps be asked to spare the embassy. He was convinced, as he cabled Molotov, that it was no coincidence that the Soviet embassy was particularly targeted by the Germans. He attributed it to Ribbentrop’s “extreme hostility” towards him personally, dating back to the German foreign minister’s time as ambassador to London. “It may seem a fantasy,” he concluded, “but we now live in fantastic times.”

A journalist described a tour he was given of the £1,500 (approximately £65,000 in today’s money) air-raid shelter constructed “many feet below garden level” at the Soviet embassy (still in situ today!):“The tube, of reinforced concrete, is the size of that in London’s underground railways; it is covered by a foot of reinforced concrete, earth, more reinforced concrete, more earth, yet more reinforced concrete and yet much more earth. The whole is well ventilated and has several compartments. One is for the Ambassador and Mme. Maisky; here I saw a portable wireless set (the house manager promptly obtained Moscow on the short-wave), a house telephone, a central exchange telephone, two forms of lighting, good bedding (tasteful blue satin). The embassy has a special plant for cleaning air in the shelter; pick-axes are in position, shovels, impressive boxes full of meat in tins, sardines, peaches; also soda water, knives, forks and spoons.”

12 October 1940

What a tour that was yesterday!

A bit of history first. During the lunch which the Halifaxes arranged for Agniya and me on 10 September, we spoke at length about air raids and bomb shelters. Some three days earlier, the Germans had launched their air offensive against London. I made a tour of the East End and saw the fires and destruction in the port area. I was struck by the paucity of shelters in this part of London, fewer than in other districts with which I am more familiar…. Halifax promised to organize the tour. I decided to accept the invitation and visited the East End yesterday with Agniya.

Our ‘guide’ was Admiral Evans, who has just been appointed ‘dictator’ of the London bomb shelters. … We were out and about for some four hours, walking, inspecting the shelters, asking questions, exchanging opinions. Summing up my impressions, I must say that all the shelters we saw except one are worthless when it comes to safety. At best they may protect from shrapnel. But they wouldn’t save anyone from a direct hit.

Admiral Evans cuts an extraordinarily colorful figure. What’s more, he is a first-class demagogue, of the classically English variety. I saw this for myself when we arrived in Tilbury. It was already 6.30pm, and a sizeable crowd had gathered in and around the shelter. Anything up to 2,000 people, I would guess…. we went to see the tunnel. By this point the assembled public already knew who had come. They greeted us with loud cheers:“Hurrah! Long live the Soviet Union!”

Agniya and I were surrounded on all sides. People shook our hands, shouted enthusiastically, punched the air, and embraced us. But the admiral kept his head. He took us by the arm and the three of us, accompanied by a local warden and a single policeman, proceeded to the tunnel. We observed the primitive – very primitive – sleeping arrangements which the East Enders had devised for themselves. The place was crowded and filthy, with wretched bedding on the stone floor, heaps of junk, and hundreds of children of all ages and appearances. The variety of individuals, and the variety of their conditions, was astonishing. I saw emaciated and hungry faces, and next to them red, well-fed physiognomies which belonged, I reckon, to the category of Whitechapel shopkeepers. Tall phlegmatic Englishmen jostled with rowdy Irishmen and nervously mobile Jews. Yes, the whole ethnographic spectrum of the East End was there.

Suddenly the admiral turned to the warden accompanying us and exclaimed: “Gather the people! I want to say a few words to them.”

The warden jumped on a platform of sorts and set about shouting at the top of his voice, waving his arms: “Over here! Over here! Admiral Evans will speak!” Agniya and I stood at the foot of the platform, trying to keep in the shadows, and waited with curiosity to see what would happen next. Suddenly the admiral bent down towards us and, gesturing emphatically, addressed me: “And what about you? Over here please! Over here!”

The admiral started tugging me and Agniya onto the platform. Someone helped us from behind and a moment later we were standing side by side with the admiral, who was waving his arms about energetically and shouting to the crowd: “Come closer! Closer! Don’t be shy!”

The people moved closer, bunching up tight. Evans took off his cap, waved it, and exclaimed: “Our country is the country of fair play! Am I right?”

An uncertain rumble passed through the crowd. One could interpret it as a sign of approval or as a mark of disapproval. The admiral continued unabashed: “A few days ago the king and queen visited you here!”

The same uncertain rumble passed through the crowd, and someone in the back row cried out: “What about it?”

The admiral went on without batting an eyelid: “And today,” he shouted with sudden emphasis, “I’ve brought you a different guest! I’ve brought you the Soviet ambassador!”

And with a wide sweep of his arm, Evans gestured towards Agniya and me. Unrestrained cheering among the crowd. Everyone started shouting: “Hurrah! Long live the Soviet Union! Long live the Soviet ambassador!”

Then Evans moved on to other topics. He said he sympathized with the people of the East End with all his heart. He couldn’t promise them miracles, but he was doing all he could to improve the situation. Half of the tunnel had been freed to turn it into a shelter. It had been cleansed of rubbish and stench. That was progress, but it was just the beginning.

“I’ll give you four thousand beds within the week!” the admiral cried in a stentorian voice. “Would you like that?”

Needless to say, the crowd welcomed the admiral’s announcement with thunderous cheers.

…The admiral mopped his forehead, put on his cap, and we all moved to the edge of the platform in order to get down. I already considered myself ‘saved’: given my delicate diplomatic status, it would have been a bit embarrassing for me to speak at this improvised meeting in the East End. So I hastened to get down, when I was suddenly met with deafening cries:“Maisky! Speech! Speech!”

Smiling broadly in all directions, I did my best to get out of it, but the shouts grew louder and louder and the people standing in the front rows rushed towards the platform to prevent my descent. The admiral spread out his arms, and giving me a friendly slap on the shoulder exclaimed: “And really, why not say a couple of words? Speak! You must speak!”

All escape routes had been cut off. Standing on the edge of the platform, I gestured for silence and said: “On behalf of my wife and myself I thank you kindly, friends, for the cordial welcome which you have given us here today.”

My voice was too weak for the gigantic space, but the crowd responded with frenzied shouts: “Hurrah! Hurrah!”

“I’m especially touched by this welcome,” I continued, “because I well understand that your greetings are addressed not so much to me and my wife as to the country I represent.”

The shouts grew even wilder. A section of the crowd started singing the ‘Internationale’.

“Let me thank you once more, with all my heart!” I concluded and began getting down from the platform.

A few seconds later and we were all on the ground. The crowd was delirious. A path opened for the three of us – myself, Agniya, and the admiral. Agniya and I were once again squeezed on all sides, embraced, and shaken by the hand. An elderly woman with light brown hair and a face webbed with deep wrinkles cried out in Russian:“Our Russia is still alive!”

Hundreds of people on both sides raised their clenched fists in salutation. The Internationale sounded louder and louder.

“What are they singing?” asked the admiral naively. “Red Flag?”

“No,” I replied. “They are singing the Internationale. It’s our Soviet state hymn.”

“Is that right?” The admiral was surprised. “I had never heard it before.”

We arrived, at last, at our cars and climbed in, to the accompaniment of loud shouts: “Long live the Soviet Union!”

Once again, the Internationale. Once again, raised fists.

The admiral was somewhat amazed. He had hardly expected the Soviet ambassador to be accorded such a warm welcome. But he lost neither his presence of mind nor his good cheer. We head off to the embassy for a cup of tea. And on the way I thought: “This is how the East End greets the Soviet ambassador today. If the war lasts two more years, Piccadilly will greet him in a similar way.”…

Translated by Oliver Ready and Tatiana Sorokina

Read more extracts from Gabriel Gorodetsky’s The Maisky Diaries, Red Ambassador to the Court of St James’s, 1932-1943.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.