Korean nuclear tension: Apocalypse... almost now

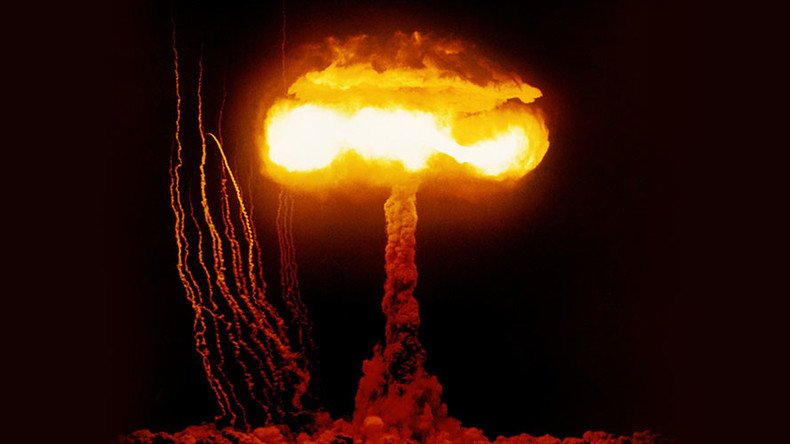

The saber rattling and harsh rhetoric during the current nuclear standoff on the Korean Peninsula should remind mankind of something we have forgotten. Atomic weapons are terrifying things, and talk of using them should be a taboo subject.

A week or so ago, I found myself reading Agatha Christie’s 80th, and penultimate, book, "Passenger to Frankfurt," and its relevance to today struck me. The book was published in 1970, with the subtitle “an extravaganza,” is an utter failure and was often characterized as an “incomprehensible muddle”; however, this "muddle" is not due to Christie’s old age or senility: instead, its causes are clearly political.

Passenger to Frankfurt is Christie’s most personal, intimately felt, and at the same time most political novel. It expresses her personal confusion, her feeling of being totally at a loss with what was going on in the world in the late 1960s – the drugs, the sexual revolution, student protests, murders, etc. So it's no wonder that Passenger to Frankfurt is not a detective novel. There is no murder, no logic, and deduction. This feeling of the collapse of the elementary cognitive mapping, this overwhelming fear of chaos, is rendered precisely in Christie’s introduction to the novel:

“Hold up a mirror to 1970 in England. Look at that front page every day for a month, make notes, consider and classify. Every day there is a killing. A girl strangled. An elderly woman attacked and robbed of her meager savings. Young men or boys attacking or attacked. Buildings and telephone kiosks smashed and gutted. Drug smuggling. Robbery and assault. Children missing and children’s murdered bodies found not far from their homes. Can this be England? Is England really like this? Not yet, but it could be. Fear is awakening, a fear of what may be. And not only in our own country. There are smaller paragraphs on other pages giving news from Europe, from Asia, from the Americas, in Worldwide News. Hi-jacking of planes. Kidnapping. Violence. Riots. Hate. Anarchy. All growing stronger. All seeming to lead to worship of destruction, pleasure in cruelty. What does it all mean?”

Is our era with “leaders” like Donald Trump and Kim Yong Un not as crazy as her vision? Are we today not all like a bunch of passengers to Frankfurt?

So what does all this mean? In the novel, Christie provides her answer – a terrible worldwide conspiracy which has something to do with Richard Wagner and "The Young Siegfried." We learn that, toward the end of World War II, Hitler went to a mental institution, met with a group of people who thought they were Hitler, and exchanged places with one of them, thus surviving the war. He then escaped to Argentina where he married and had a son who was branded with a swastika on his heel – “The Young Siegfried.” Meanwhile, in the book's present, drugs, promiscuity, and student protests are all secretly caused by Nazi agitators who want to bring about anarchy so that they can restore Nazi domination on a world scale.

Global delirium

This “terrible worldwide conspiracy” is, of course, ideological fantasy at its purest: a weird condensation of the fear of extreme right and extreme left. The least we can say to Christie’s credit is that she locates the heart of the conspiracy to the extreme right (neo-Nazis) and not in any of the other usual suspects (Communism, Jews, Muslims, etc.). The idea neo-Nazis were behind the ’68 student protesters and sexual liberation struggle, with its obvious madness, nonetheless bears witness to the disintegration of a consistent cognitive mapping of our predicament.

Christie is compelled to take refuge in such a crazy paranoiac construct as the only way to introduce some order and meaning into the utter confusion and panic she found herself in. But is her vision really too crazy to be taken seriously? Is our era with “leaders” like Donald Trump and Kim Yong Un not as crazy as her vision? Are we today not all like a bunch of passengers to Frankfurt? Our situation is messy in a way very similar to the one described by Christie: a rightist government enforcing workers’ rights (in Poland), a leftist government pursuing the strictest austerity politics (in Greece). Thus, it's no wonder that, to regain a minimal cognitive mapping, Christie resorts to WWII, “the last good war,” retranslating our mess into its coordinates.

One should nonetheless note how the very form of Christie’s answer (one big secret agent behind it all) strangely mirrors the fascist idea of the Jewish conspiracy: how there is one big Nazi plot behind which lies the explanation to everything. And, today, the extreme populist right proposes a similar explanation of the Muslim immigrant “threat.” In antisemitic imaginary, the “Jew” is the invisible master who secretly pulls the strings, which is why Muslim immigrants are NOT today's Jews: they are all too visible, not invisible. They are clearly not integrated into our societies, and nobody claims they secretly pull strings - if one sees in their “invasion of Europe” a secret plot, then Jews have to be behind it. As was the case in a text that recently appeared in one of the main Slovenian Rightist weekly journals where we could read: “George Soros is one of the most depraved and dangerous people of our time,” responsible for “the invasion of the negroid and Semitic hordes and thereby for the twilight of the EU... as a typical Talmudo-Zionist, he is a deadly enemy of Western civilization, the nation-state and white, European man.”

His goal is to build a “rainbow coalition composed of social marginals like faggots, feminists, Muslims and work-hating cultural Marxists,” which would then perform “a deconstruction of the nation-state, and transform the EU into a multicultural dystopia of the United States of Europe.” Furthermore, Soros is inconsistent in his promotion of multiculturalism: “He promotes it exclusively in Europe and the USA, while in the case of Israel, he, in a way which is for me totally justified, agrees with its monoculturalism, latent racism and building a wall. In contrast to the EU and USA, he also does not demand from Israel to open its borders and accept ‘refugees.' A hypocrisy appropriate to Talmudo-Zionism.”[Quoted from Bernard Brščič, ‘George Soros is one of the most depraved and dangerous people of our time’ (in Slovene), Demokracija, August 25 2016, p. 15.]

This is the end?

Is this disgusting fantasy which brings together antisemitism and Islamophobia so different from the one staged by Christie? Are they both not a desperate attempt to orient oneself in confused times? The extreme oscillations in the public perception of the Korean crisis are significant as such. One week we are told we are on the brink of nuclear war, then there is a week of respite, then the war threat explodes again. When I visited Seoul in August 2017, my friends there told me there is no significant threat of a war since the North Korean regime knows it cannot survive it, but now the South Korean authorities are preparing the population for a nuclear war.

In such a situation, where the apocalypse is on the horizon, one should bear in mind the standard logic of probability no longer applies, we need a different logic, described by Jean-Pierre Dupuy: “The catastrophic event is inscribed into the future as destiny, for sure, but also as a contingent accident… if an outstanding event takes place, a catastrophe, for example, it could not have taken place; nonetheless, insofar as it did not occur, it is not inevitable. It is thus the event’s actualization – the fact that it takes place – which retroactively creates its necessity.”[ Jean-Pierre Dupuy, Petite metaphysique des tsunami, Paris: Seuil 2005, p. 19.] Dupuy provides the example of the French presidential elections in May 1995; here is the January forecast of the main polling Institute: “If on next May 8th, Mr (Édouard) Balladur will be elected, one can say the presidential election was decided before it even took place.”

The moment we fully accept the fact that we live on Spaceship Earth, the task that urgently imposes itself is that of civilizing civilizations themselves, of imposing universal solidarity and cooperation among all human communities.

When applied to the recent tension in Korea, this means: IF the war explodes, it will be necessary and inevitable; IF war will not explode, it was all a false alarm. This, according to Dupuy, is also how we should approach the prospect of nuclear (or ecological) catastrophe: not to “realistically” appraise the possibilities of the catastrophe, but to accept it as our fate, as unavoidable, and then, on the background of this acceptance, we should mobilize ourselves to perform the act which will change destiny itself and thereby insert a new possibility into the situation. Instead of saying “the future is still open, we still have the time to act and prevent the worst,” one should accept the catastrophe as inevitable, and then work to undo what is already “written in the stars” as our destiny.

What is needed is no less than a new global anti-nuclear movement, a global mobilization that would exert pressure on nuclear powers and act aggressively, organizing mass protests and boycotts, while denouncing our leaders as criminals and the like. It should focus not only on North Korea but also on those super-powers who assume the right to monopolize nuclear weapons. The very public mention of the use of nuclear weapons should be treated as a criminal offense. And more than that, a global change in our stance is needed, what Peter Sloterdijk calls “the domestication of the wild animal culture.”

Till now, each culture disciplined and educated its own members and guaranteed civic peace among them in the guise of state power, but the relationship between different cultures and states was permanently under the shadow of potential war, with each state of peace nothing more than a temporary armistice. As Hegel conceptualized it, the entire ethic of a state culminates in the highest act of heroism, the readiness to sacrifice one’s life for one’s nation-state, which means that the wild barbarian relations between states serve as the foundation of the ethical life within a state. Is today’s North Korea with its ruthless pursuit of nuclear weapons, and rockets to deliver them to distant targets, not the ultimate example of this logic of unconditional nation-state sovereignty?

However, the moment we fully accept the fact that we live on Spaceship Earth, the task that urgently imposes itself is that of civilizing civilizations themselves, of imposing universal solidarity and cooperation among all human communities. A task rendered all the more difficult by the ongoing rise of sectarian religious and ethnic “heroic” violence and readiness to sacrifice oneself (and the world) for one’s specific cause.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.