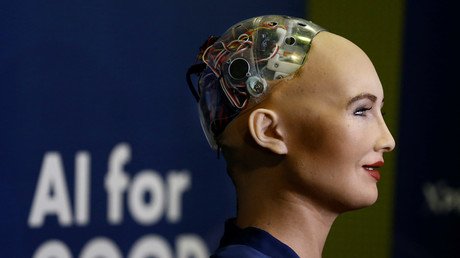

More and more jobs are at risk of being outsourced to a cheaper and more efficient robot. Is your job one of them – and if so, will a universal basic income (UBI) prove to be the panacea for increased automation?

Many or most of us wish we could work shorter hours and have more time for family, friends and fun. The struggle to reduce the working day spans several generations. In the 19th century our ancestors, fighting tooth-and-nail with banner in hand, won several victories. Following the February 1848 Revolution in France, the nation’s working day was capped at 12 hours. Four years earlier in the UK, the British Factory Act had reduced the maximum working day to 12 hours for adults and 6.5 hours for children. In 1868 the US congress approved an “Eight Hour Work Day for Employees of the Government of the United States” and following the two revolutions of 1917, Russia’s new authorities reduced the working day to eight hours and introduced both pensions and unemployment pay. Other governments have followed suit over the past century and many countries now have laws limiting the official working week for most jobs to around 40 hours.

Alongside the battle to reduce daily working hours, over the past two centuries workers have also fought a struggle to safeguard their jobs and livelihoods in the face of increased mechanization. In the early 19th century groups of craftsmen and workers, known as Luddites, smashed newly developed factory machines which they feared would make their craft redundant and force unemployment upon them. Over the past several decades, advancements in electronics and computing have revolutionized the working world, creating new jobs and industries. However, the onward march of technology has trampled on the manufacturing industries of Europe and North America, causing the loss of millions of jobs as humans become replaced with cheaper and more efficient robots who work longer hours and don’t require holidays, sick pay or pensions. In the decade between 2000-2010, in the US alone jobs in the manufacturing industry declined by 5.6 million. However, output increased as the vast majority of job losses were due to automation rather than international trade agreements.

Ongoing advancements in technology are expected to lead to further job losses in future. Accountancy firm PwC predict that in the UK up to 30 percent (10 million) existing, mostly low-skilled and manual jobs could be taken over by robots within the next 15 years. Economies with comparable figures are the US (38 percent), Germany (35 percent) and Japan (21 percent). According to PwC’s chief economist John Hawksworth “jobs where you've got more of a human touch, like health and education,” which do not easily lend themselves to automation are expected to be somewhat protected. Some job losses could be offset as new industries develop on the back of the growth in robotics and AI. However, there are concerns that workers lacking the necessary skills to prosper in the coming years could be left behind in this 21st century industrial revolution, leading to greater income inequality.

Introducing a universal basic income for all citizens, to create a safety net for those whose jobs end up being done by robots, has been touted as a solution. Billionaires Richard Branson, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg have spoken in favor of this initiative. Branson comments: “Basic income is going to be all the more important. If a lot more wealth is created by AI, the least that the country should be able to do is that a lot of that wealth that is created by AI goes back into making sure that everybody has a safety net.”

Finland is currently testing out a two-year scheme to give all citizens €560 a month and parts of the Netherlands, Hawaii and Ontario are considering, or in the process of conducting small experiments, giving all citizens a basic income.

The idea of a universal basic income for all citizens, regardless of employment status, is an attractive one. Few would disagree with the idea of creating a safety net to ensure that someone who is down on their luck or unemployed could afford food, shelter and clothing at a minimum. However, extending universal basic income to the entire working population of a large country could be less feasible than introducing it in certain cities or for select populations. For example, there are presently around 32 million employed adults in the UK plus almost another nine million economically inactive individuals aged 16-64. If each of these roughly 40 million people received, say, £500 each month, this would equate to almost £20 billion a month or £240 billion a year – approximately double the annual NHS budget. It’s difficult to imagine this occurring at a time when governments across Europe are taking every opportunity to implement austerity.

Billionaire Elon Musk, a proponent of universal basic income, feels that in the face of increased automation “People will have time to do other things, more complex things, more interesting things… Certainly more leisure time.” Some individuals who find their jobs taken over by robots might seize the opportunity to spend more time with family and friends or relish the chance to pursue a favorite hobby or study a topic of interest, whilst receiving a modest allowance. However, some people might find themselves struggling to cope with the lack of a daily routine alongside social isolation and an increasingly sedentary lifestyle, all of which are to some degree tempered by having a job, especially one involving physical labor.

The socioeconomic paradigm shift resulting from the combination of automation and a universal basic income would be unprecedented as relationships between workers, bosses, society and the government would be drastically affected. It might even be more profitable for owners of large industries to pay their workers a subsistence wage to stay at home, whilst outsourcing their jobs to robots and computers who don’t require breaks, sick pay or pensions, won’t go on strike on account of poor working conditions or inadequate health and safety standards, and won’t raise thorny issues such as asking for a share of company profits in exchange for labor performed or suggesting factories be run as workers’ cooperatives. Maintaining a high profit margin without having to deal with trade unions, strikes or irate workers: a capitalist’s dream. Meanwhile, the workers can stay at home, isolated from each other, as they enjoy the latest soap opera and read juicy tabloid gossip. Whatever happens, one thing is certain: society, work and our daily lives are set to see radical change over the coming decades.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.