Everyone who’s asking “why did the stock market crash Monday?” is asking the wrong question. The real poser is “why did it take so long for this crash to happen?”

The crash itself was significant—Donald Trump’s favorite index, the Dow Jones Industrial (DJIA) fell 4.6 percent in one day. This is about four times the standard range of the index—and so according to conventional economics, it should almost never happen.

Of course, mainstream economists are wildly wrong about this, as they have been about almost everything else for some time now. In fact, a four percent fall in the market is unusual, but far from rare: there are well over 100 days in the last century that the Dow Jones tumbled by this much.

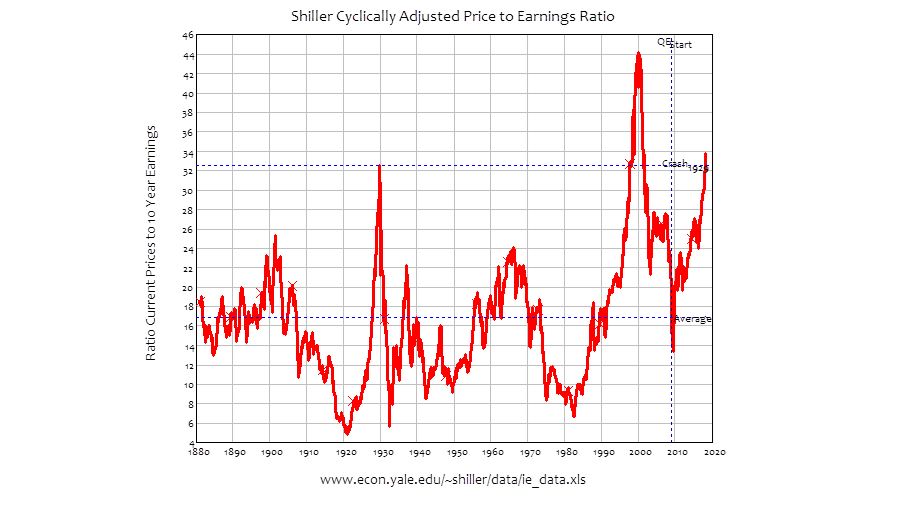

Crashes this big tend to happen when the market is massively overvalued, and on that front this crash is no different. It’s like a long-overdue earthquake. Though everyone from Donald Trump down (or should that be “up”?) had regarded Monday’s level and the previous day’s tranquillity as normal, these were in fact the truly unprecedented events. In particular, the ratio of stock prices to corporate earnings is almost higher than it has ever been.

More To Come?

There is only one time that it’s been higher: during the DotCom Bubble, when Robert Shiller’s “cyclically adjusted price to earnings” ratio hit the all-time record of 44 to one. That means that the average price of a share on the S&P500 was 44 times the average earnings per share over the previous 10 years (Shiller uses this long time-lag to minimize the effect of Ponzi Scheme firms like Enron).

The S&P500 fell more than 11 percent that day, so Monday’s fall is minor by comparison. And the market remains seriously overvalued: even if shares fell by 50 percent from today’s level, they’d still be twice as expensive as they have been, on average, for the last 140 years.

After the 2000 crash, standard market dynamics led to stocks falling by 50 percent over the following two years, until the rise of the Subprime Bubble pushed them up about 25 percent (from 22 times earnings to 28 times). Then the Subprime Bubble burst in 2007, and shares fell another 50 percent, from 28 times earnings to 14 times.

This was when central banks thought The End of the World Is Nigh, and that they’d be blamed for it. But in fact, when the market bottomed in early 2009, it was only just below the pre-1990 average of 14.5 times earnings.

Safe Havens

That valuation level, before central banks (staffed and run by people with PhDs in mainstream economics) decided that they knew how to manage capitalism, is where the market really should be. It implies a dividend yield of about six percent in real terms, which is about twice what you used to get on a safe asset like government bonds—which are safe, not because the governments and the politicians and the bureaucrats that run them are saints, but because a government issuing bonds in its own currency can always pay whatever interest level it promises. There’s no risk that it can’t pay, and it can’t go bankrupt, whereas a company might not pay dividends, and it can go bankrupt.

Now shares are trading at a valuation that implies a three percent return, as if they’re as safe as government bonds issued by a government which owns the bank that pays interest on those bonds. That’s nonsense.

And it’s a nonsense for which, ironically, central banks are responsible. The smooth rise in stock market prices which led to the levels that preceded Monday’s crash began when central banks decided to rescue the economy by “Quantitative Easing (QE).” They promised to do “whatever it takes” to drive shares up from the entirely reasonable values they reached in late 2009, and did so by buying huge amounts of government bonds back from private banks and other financial institutions (pension funds, insurance companies, etc.). In the USA’s case, this amounted to $1 trillion per year—equal to about seven percent of America’s annual output of goods and services (GDP or “gross domestic product”). The Bank of England brought about £200 billion worth, which was an even larger percentage of GDP.

With central banks buying that volume of bonds, private financial institutions found themselves awash with money, and spent it buying other assets to get yields—which meant that QE drove up share prices as banks, pension funds and the like bought them with money created by QE.

Blind Oversight

So this is the first central bank-created stock market bubble in history, and central banks have just had the first stock market crash where the blame is entirely theirs.

Were this a standard, private hysteria and leverage driven bubble, we could well be facing a further 50 percent fall in the market—like what happened after the DotCom crash. This would bring shares back to the long-term average of 17 times earnings.

Instead, what I believe will happen is that central banks, having recently announced that they intend to end QE, will restart it and try to drive shares back to what think are “normal” levels, but which are at least twice what they should be.

As I said in my last book ‘Can we avoid another financial crisis?’ QE was like Faust’s pact with the Devil: once you signed the contract, you could never get out of it. They’ll turn on their infinite money printing machine, buy bonds off financial institutions once more, and give them liquidity to pour back into the markets, pushing them once more to levels that they should never rightly have reached.

This, of course, will help to make the rich richer and the poor poorer by further increasing inequality. Which is arguably the biggest social problem of the modern era. So, as well as being incompetent economists these mainstreamers are today’s Marie Antoinette. Let them eat cake, indeed.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.