Technology gives us the opportunity to wage war from afar at a greatly reduced risk to our armed forces. But is removing the horror of war a slippery slope to reducing the threshold for conflict?

Going to war usually boosts a politician’s approval ratings and can be a useful distraction from domestic problems. Yet public opinion typically turns sour when a steady stream of soldiers start returning in body bags and candid reportage from the war zone reveals unpleasant truths. The public’s distaste at seeing ‘our boys and girls’ returning in coffins or missing limbs somewhat hampers the abilities of warmongers to fulfil their wish-list. In the 1860s Confederate General Robert E Lee remarked: “It is well that war is so terrible, otherwise we should grow too fond of it”.

21st century technology is giving wealthier countries the opportunity to wage war from afar, in an asymmetrical manner, where their own forces can be spared the risk of death and injury. There has been an exponential increase in the production and proliferation of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAV), more commonly known as drones, over the past 15 years. Drones can be used for surveillance, reconnaissance or assassination. After the US first used a UAV in 2001 to assassinate a high ranking al-Qaeda militant in Afghanistan, a growing number of countries began manufacturing or using armed drones. In the early days of drone warfare both the US Air Force and Britain’s Royal Air Force (RAF) operated drones flying over Afghanistan from Creech Air Force Base in the Nevada desert, 7000 miles away. The UK began operating its drone fleet from home soil at RAF Waddington, Lincolnshire in 2013.

Drones have allowed the US to silently observe or kill individuals across several countries at virtually no risk to their armed forces. In 2011 the UK’s Ministry of Defence published a document in which is stated: “It is essential that, before unmanned systems become ubiquitous (if it is not already too late) that we consider this issue and ensure that, by removing some of the horror, or at least keeping it at a distance, that we do not risk losing our controlling humanity and make war more likely”.

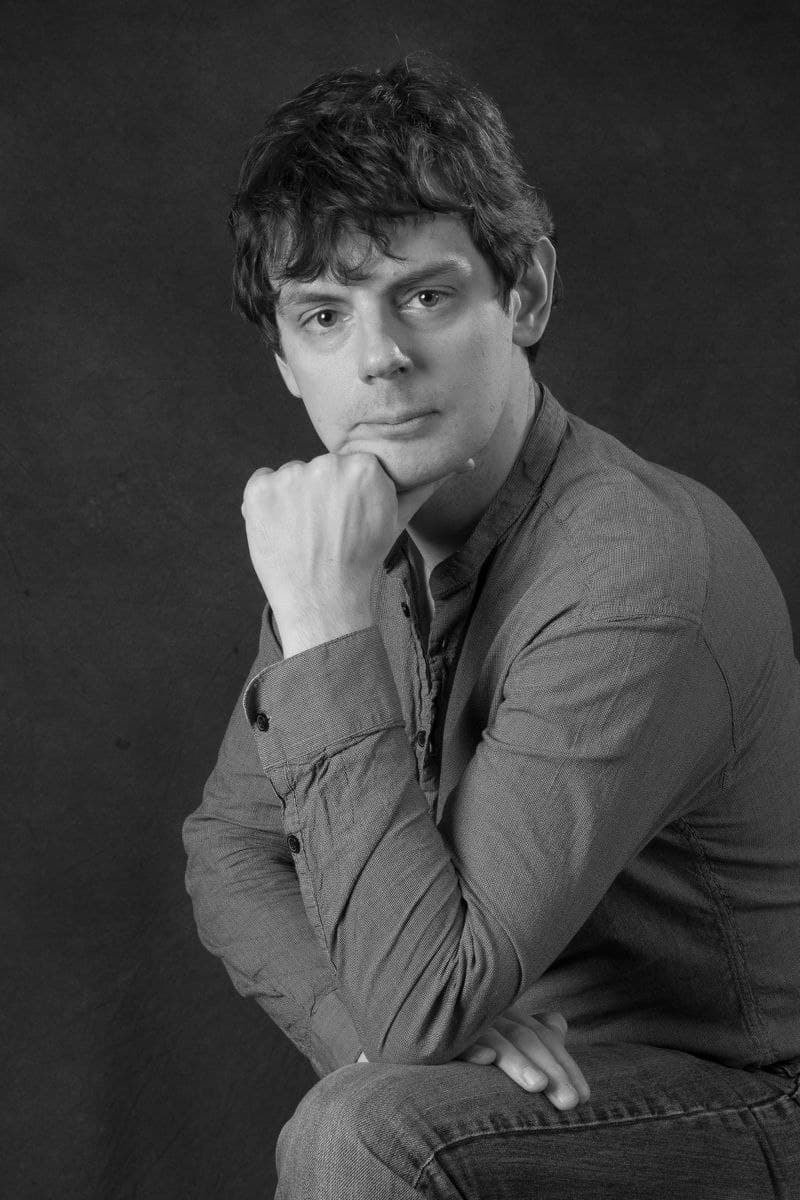

In 2012 I co-authored a report on behalf of UK charity Medact - ‘Drones: the physical and psychological implications of a global theatre of war’ - in which we examined the impact of this new form of warfare upon civilians and considered the moral, legal and geopolitical implications of a globalised theatre of war where a nation could remotely eliminate its enemies anywhere across the globe, including outside designated conflict zones.

For example, the US has performed hundreds of drone strikes in Pakistan against the Taliban and other militants even though the US and Pakistan are not at war. These drone strikes have caused numerous civilian deaths. There have even been reports of good samaritans and medical personnel being attacked in a follow up drone strike whilst coming to the assistance of people injured in an earlier drone attack.

The London based Bureau of Investigative Journalism estimates that between 424-969 civilians have been killed out of a total of 2,515-4,026 dead from at least 430 drone strikes conducted by the US in Pakistan alone since 2004.

Only three countries had used armed drones at the time of our report’s publication: the US in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia and Yemen; the UK in Afghanistan; Israel in Gaza. The report warned that “Drones may become a routine weapon of war, in order to avoid anti-war sentiment and to reduce the political cost of initiating a military intervention. It is hard to imagine that the US could have undertaken military action in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Somalia and Libya in one year (2011) without drones. Drones could lead to a world of globalised warfare, in which people may find themselves within a theatre of war literally anywhere on the planet”.

America’s drone war greatly expanded during the Presidency of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Barack Obama when the CIA and other US intelligence agencies would add the names of alleged terrorists earmarked for elimination by drone onto what became informally known as the ‘kill list’ . The President then had final say over who will be killed. This included individuals in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia, who had not been formally charged or tried in a court of law.

Another aspect of drone killings involves ‘signature strikes’ whereby a drone operator identifies individuals whose behaviour is deemed suspect and who might then be eliminated, if the order is given from above. In 2012, 26 members of Congress signed a letter asking for the legal basis and due process behind the Obama administration’s sanctioning of signature strikes and expressed caution over the lack of transparency, accountability or oversight pertaining to America’s drone war.

By 2018 the armed drone club had grown to 12 members (China, Iran, Turkey, Pakistan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, Nigeria in addition to the original three), who had either manufactured their own armed UAVs or purchased them from other nations. A number of non-state actors (ISIS, PKK, Hezbollah, Hamas, Houthi militants) have also reportedly used drones in combat, albeit cruder versions than those used by the aforementioned states such as small drones outfitted with explosives that are made to crash into a target in a Kamikaze-like manner. Russia and India are among several other countries believed to be developing armed drones. Russia has however already developed its own unmanned submarine, or autonomous underwater vehicle, capable of carrying nuclear warheads.

While the USA and Israel are globally recognised drone exporters they may soon face competition from China, which has recently begun exporting armed drones. Chinese models are believed to be variants of US made Predator and Reaper drones that sell at a fraction of the price. Pressure from the US drone lobby led to the US easing restrictions on exporting armed UAVs in April 2018.

Drones are presently still under the direct control of a human operator, albeit one who may be thousands of miles away. The next stage in the evolution of drone warfare is predicted to be a move from unmanned to increasingly autonomous drones that can select their own targets and ultimately operate without human oversight. Such technology is being tested and developed and “influential people like [the late] Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk and Steve Wozniak have already urged a ban on warfare using autonomous weapons or artificial intelligence,” according to NATO Review magazine.

Proponents of drone warfare argue that using UAVs is preferable to risking soldiers’ lives. Saving lives is laudable but removing the horror of war, at least for the side possessing drones, is the start of a slippery slope where the threshold of going to war decreases. Rather than finding ways to make war easier, policy makers ought to spend time, effort and money on trying to prevent conflict. War may at times be necessary but few would argue that the conflicts where drones have been used, such as the Western led interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria, were unavoidable let alone beneficial for those countries and their people. A future where a globalised battlefield becomes the norm and individuals deemed a threat to the US, or any other power with the means, can be eliminated without due process or trial is a dark one indeed.

The possibility of increasingly autonomous warfare systems would allow decision makers to further wash their hands from the horrors of war. Who would be held responsible if a fully autonomous drone chose the ‘wrong’ target or caused civilian casualties? Furthermore there is always the possibility that any robotic system can be hacked or commandeered by other countries or non-state actors.

Legally binding international conventions controlling the manufacture, use and sale of armed drones ought to have been ratified before the technology became available. As drone use is now too extensive to easily control, there should at least be a move to channel the technology in a direction that benefits humanity as a whole. Although the profit margins may be much smaller than in war, drones can be used to deliver supplies and medicines to remote areas, take part in search and rescue missions in disaster zones, or monitor large wildlife reserves for poachers. We can decide how this new technology shapes our future. A challenge for humanity is that technology is developing faster than the legal, ethical and moral codes governing its use.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.