How US hardliners ensured Soviet withdrawal did not lead to peace in Afghanistan

Thirty years after the withdrawal of the last Soviet forces from Afghanistan, the US is still fighting the monster they helped create in their anti-Soviet crusade.

February 15, 1989. The date when the Soviet Army left Afghanistan for the last time. Trying to defend the left-wing government in Kabul from US-backed mujahideen had cost the Soviet Union countless millions of rubles and the lives of over 15,000 soldiers. So you can understand why Mikhail Gorbachev wanted out. He actually wanted to withdraw earlier. But the Kremlin’s proposals for a negotiated settlement were blocked by neocons in the Reagan administration, who met attempts at compromise from Kabul and Moscow with intransigence and increased support for the most militant factions.

Gorbachev warned of the global consequences of an extremist takeover in Afghanistan, but his words went unheeded. The US, in their determination to give the Soviet Union its own Vietnam, helped create a Frankenstein monster which they are still fighting, or pretending to fight, today.

Let’s go back to the late 1970s.

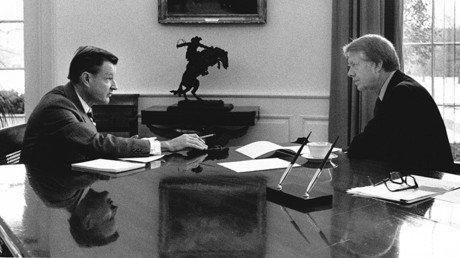

One of the great myths about the Afghanistan war is that the US only started backing Islamist fighters after the Soviet Union tanks rolled into the country on December 24, 1979. As I noted in a previous op-ed in 1988, Zbigniew Brzezinski, Jimmy Carter’s hawkish and fanatically anti-Russian national security adviser, admitted that he got the US president to sign the first order for secret aid to ‘rebels’ in July 1979, a full five months before the Soviet Army rolled in. The move was expressly designed to provoke a military response from the Kremlin.

“I wrote a note to the president in which I explained to him that in my opinion, this aid was going to induce a Soviet military intervention,” Brzezinski said. Even before that, US officials had been meeting with ‘rebel’ leaders. In 1977, Zbig had set up the Nationalities Working Group, whose goal was to weaken the Soviet Union by stirring up ethnic and religious tensions.

US funding for anti-government fighters increased sharply in 1980 and continued to increase throughout that decade. By 1987, the US was spending $630 million a year in Afghanistan. The war could have been long over if Washington had really wanted it.

“From the archives in Moscow we know that the Soviets were trying to disengage honorably, leaving behind a friendly regime in Kabul,” write Jeremy Isaacs and Taylor Downing in their book ‘Cold War.’ But the talks came to naught as both the US and Pakistan wanted to keep the Soviets bogged down.

Another great myth about the Afghanistan war, and this one is often promulgated by critics of the US, is that the insurgents were all fanatical and embryonic Al-Qaeda types. They weren’t. There were many brave and honorable fighters in their ranks who simply didn’t like the policies of the Moscow-backed government.

As the conflict dragged on, however, and an increased number of fighters poured in from other countries, the ‘struggle’ began to be influenced by more extreme actors. These actors received support from the US, which was terrified that the conciliatory overtures made by Afghan President Babrak Karmal and his successor Mohammad Najibullah, who both reached out to the Islamists, would be accepted. In his book ‘Web of Deceit,’ author Mark Curtis cites Afghanistan expert John Cooley who said that the CIA, “delighted by his impeccable Saudi credentials, gave Osama Bin Laden free reign” in Afghanistan to organize Islamic fighters. CIA support even helped Bin Laden build an underground training camp in Khost. Some 15 years later, let’s not forget, the US invaded Afghanistan on the premise of toppling a government which they claimed was sheltering Bin Laden, who was now billed as Public Enemy Number One and the most wicked man in the world.

Backing extremist factions within the mujahideen at the expense of more moderate ones was not the only way the US kept the fires burning in Afghanistan. In 1986 alone, the US spent $43 million on school textbooks for children in rebel areas, which proclaimed that ‘infidels are our enemy’ and encouraged attacks on Soviet and government forces.

After Soviet troops finally left in 1989, the US, in breach of its promises, continued to arm the mujahideen in their battle to topple the Afghan government. This, together with Russian President Boris Yeltsin’s cutting off of all aid to Kabul, had disastrous consequences for the Afghan people. In April 1992, Najibullah’s administration fell and what Mark Curtis describes a ‘a reign of terror’ was launched by Gulbuddin Hekmatyar, a mujahideen warlord who once met Margaret Thatcher for tea in Downing Street.

In 1994, the Taliban, a fundamentalist Sunni movement, were formed and in 1996 they took Kabul. Najibullah, the last leader of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, was left hanging from a Kabul lamppost.

Five years after that, the US and its allies were at war with the Taliban, an ‘enemy’ who would not have existed if the US and its allies had followed a different policy towards Afghanistan.

Today it’s Russia which is accused of supplying and siding with the Taliban, who only came to power because of American attempts to overthrow a pro-Moscow Afghan government, and Russian President Boris Yeltsin’s abandonment of an old ally in 1991. You really couldn’t make it up, could you?

Since the US launched ‘Operation Enduring Freedom’ in 2001, over 100,000 Afghans and 3,400 coalition troops have been killed. Last year, civilian deaths and injuries from explosive weapons rose by 36 percent to 4,260.

Peace looks as far away as ever, because every time we get a chance of a settlement, the US seems to sabotage it, as it did throughout the 1980s.

Let’s leave the last words on this whole sorry saga of unnecessary bloodshed to Hamid Karzai, the former mujahideen fundraiser who became Afghan President with US backing in 2001. In 2014 Karzai admitted:

“Today, I tell you again that the war in Afghanistan is not our war, but imposed on us and we are the victims... One of the reasons was that the Americans did not want peace because they had their own agenda and objectives.”

Follow Neil Clark @NeilClark66 and @MightyMagyar

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.