Puritan gatekeepers’ wish to censor Paul Gauguin paintings demeans art

Paul Gauguin is under attack from supporters of post-colonialism and feminism because of his erotic paintings of Polynesian girls and women. Is censoring art of long-dead artists for moral reasons constructive?

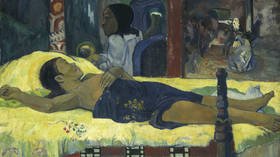

Curators of the current display of Gauguin portraits at the National Gallery in London have not included any of his famous nudes, even though they could be described as portraits. Gauguin is in the firing line because of his erotic paintings of Polynesian women and his life, while living in Polynesia from 1891 until his death in 1903. The attacks come from supporters of post-colonialism and feminism. Academic post-colonial studies treat colonialism and all its products as irredeemably unjust; feminism is deeply hostile to any sexualised depictions of women by men.

Some criticism of Gauguin has been vicious: “He was, in almost every way, an absolute prick.” “Exquisite art by the Harvey Weinstein of the 19th century,” adds another review. The exhibition seems part artistic assessment and part historical trial.

Gauguin in Polynesia

“Gauguin undoubtedly exploited his position as a privileged Westerner to make the most of sexual freedoms available to him.” So a wall text in the National Gallery, London declares. The truth of the matter is – as expected – more complicated than press and critics portray it.

Two reasons for Gauguin to visit French Polynesia were primitivism and sex. He was searching for a “primitive” culture that he could use to revitalize European art. He was also interested in the native women. Tahiti appealed to Europeans because of its climate, wildlife, food and culture; it was also famed for the attractiveness and sexual availability of its women. By the time Gauguin arrived, Polynesian customs had been almost erased by missionary conversion of islanders to Catholicism and rule of French colonists. Sexual relations between Westerners and locals were a grey area, with European and Polynesian traditions overlapping.

By taking a Tahitian mistress, Teha’amana (aged about 13 when they first met), the (married) artist probably committed deception. We do not have the testimony of Teha’amana, who died around 1919. As Elizabeth Childs points out in a catalogue essay, the situation was not a clear-cut abuse of power. Such relationships between unmarried partners – and partners different in age and national background – were not uncommon in Tahiti and it seems her family may have approved of the relationship.

The weakness of museums

How far should we go in morally judging long-dead artists?

Imposing our standards on those who lived in different eras and societies demonstrates unwillingness to empathize. Self-appointed representatives of groups, who have increasing influence over what we are allowed to see, have a righteous intolerance to anything that conflicts with how they view the world should be. Rather than examine ethical matters in a dispassionate manner, their response is ruthlessly authoritarian. These moral arbiters act like tyrannical mothers protecting their children. Yet we are not children. We have our own moral standards and life experiences; we can decide what is acceptable. No one needs protection from Gauguin paintings, which are neither dangerous nor obscene.

We do not reject theories of scientists or mathematicians because their behaviour was dubious, but we view art as having moral stature and that makes us sensitive to artists’ personal morality. Yet many of us are capable of detaching art from artist. We can separate Picasso’s infidelity from his paintings. We can love Richard Dadd’s art without condoning him killing his father.

Revenge on history

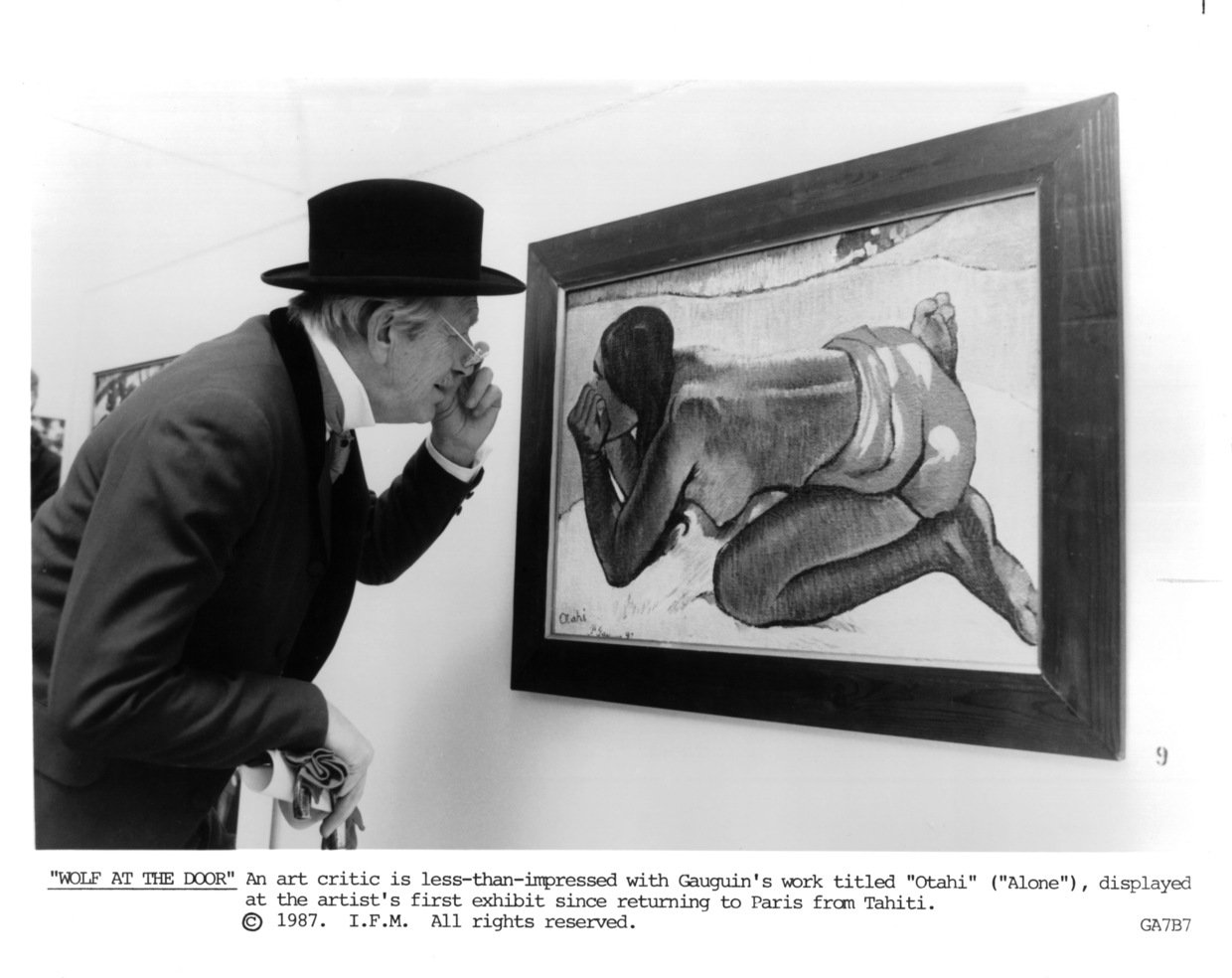

We should be aware that another motivation for censorious gatekeepers is revenge. Censoring paintings is revenge against their creator. Why should this moral criminal have art in museums, when he has perpetrated moral crimes? Some art is suppressed, and curators feel they have to publicly castigate the artist in texts. The moralising in exhibition catalogues and captions (including a recent one about Gauguin, held at the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam) demonstrates that these actions are public performance, intended to show that the cultural elite abhors “historical injustice”. This is emotional theatre which demeans art, distorts history and patronizes audiences.

The idea of censoring art for moral reasons is counterproductive. What better way of prompting people to reflect on colonial experience than by showing Gauguin’s nudes in order to make us think about the lives of these women? By hiding evidence of colonialism, puritanical gatekeepers actually make it unreal. Gatekeepers want to have authority over what we are able to access. How long until all colonial material is removed from museums? When will classical art depicting rape be removed because it might upset victims of sexual assault? Already there are campaigns demanding such actions, and museums in the West are woefully weak at articulating the Enlightenment values of museum culture that would defend museum independence.

Threatened by campaigners and battered by critics keen to display their “woke” credentials, museums in the West are a soft target. Museum staff are unwilling to defend traditional goals of their own institutions. If matters continue this way, museums will be held captive by a tiny handful of activists forever moving the goalposts.

We must reject moralising pressure groups by asserting our rights as informed independent individuals to make our own judgments about culture and history.

Subscribe to RT newsletter to get stories the mainstream media won’t tell you.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.