1945 Dresden bombing’s lesson is the same 75 years on: Might still makes right

The 75th anniversary of the bombing of Dresden should force us to understand that, unfortunately, as the Roman statesman Cicero said, “In war, the law falls silent.”

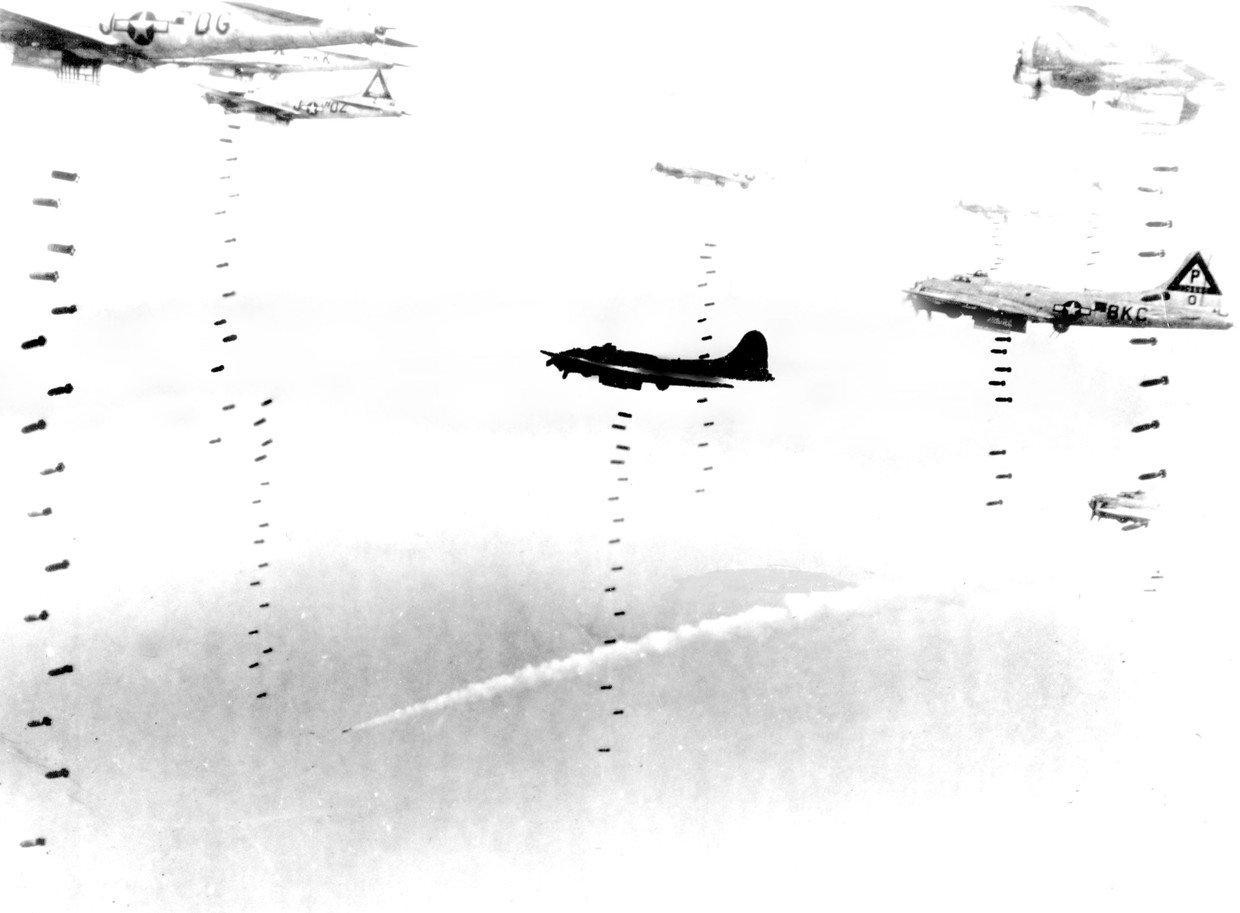

Dresden is like Auschwitz or Srebrenica, a terrible event elevated to almost mythical status because it is in fact the symbol of a wider phenomenon, in this case the bombing campaign conducted against a large number of German cities including Hamburg and Berlin. Dresden occupies this symbolic status because of the very high number of civilian deaths, most burned to death by incendiary bombs whose function was to set buildings alight, and because the town had little or no military significance.

Dresden remains today an open wound in German historical memory because German civilians were victims in their tens of thousands. Germany protested bitterly in 1991 when the British put up a statue to the chief of bomber command, Sir Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, in central London. When the Queen visited Dresden in 1992, she was booed. A book by noted German historian Jörg Friedrich, ‘The Fire: The Bombing of Germany, 1940-1945’, published in 2006, became a bestseller.

Such German anger is understandable, especially since the Nazis at Nuremberg were not indicted for the Blitz bombing of London and other British cities in 1940-1941, precisely because the British wanted to prevent them from being able to say they had done the same thing to Germany at the end of the war. The Americans, for their part, dropped a nuclear bomb on Hiroshima within days from when the Nuremberg charter was promulgated, killing over a hundred thousand Japanese civilians in one go.

With the benefit of hindsight, and in view of the fact that the Allies defeated Germany and Japan shortly after these bombings, it is argued that Dresden and Hiroshima and Nagasaki were futile and unnecessary acts of terror. It is difficult to deny that they were acts of terror but it is much more difficult to claim that they were futile. In February 1945 the war had not been won in Europe; in August 1945 it had not yet been won in Asia. On the contrary, Nazi Germany was fighting back viciously and even managed a major counter-offensive in the Low Countries in December 1944 which was only repulsed in January 1945. The air force officers deciding to bomb Germany to ruins did not know then that they were going to win the war a few months later. When they did, they claimed that the bombing, as later in Japan, had actually hastened the war’s end. Perhaps they are right.

What is certain is that the decision not to prosecute the Germans for the Blitz demonstrates the severe, indeed fatal, shortcomings of the notion of international criminal law. Punishing people for war crimes sounds fine in principle but the practice is very often abused, not least because the law is applied according to double standards.

We can see this in the history of international law: aerial bombardment was proclaimed illegal in the international peace conference held at The Hague in 1899, even before the airplane was invented, along with poison gas and dum-dum bullets. A hundred years later, the provisions on gas and dum-dum bullets remain unchanged in the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court of 1998, while the rule against the launching of projectiles and explosives from balloons or by other similar new methods has been quietly dropped.

Aerial bombardment has therefore gone from being a war crime to an instrument of the highest morality: during the bombing of Yugoslavia in 1999, the Supreme Commander of NATO General Wesley Clark said that the Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic must have felt as if he were fighting God, the implication being that NATO was enacting divine retribution by throwing down thunder and lightning from the heavens onto the miscreants below.

This judicial volte-face makes a mockery of the supposed role of law in war, something liberal activists have been trying to establish for over a century. The truth is instead much more brutal. It was first formulated over 2,000 years ago by Thucydides in his history of the Peloponnesian war: The strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must. That is the lesson of Dresden.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.