I’m as sceptical as anyone about the government’s narrative on this Covid crisis & the media hype. But 2020 WAS a deadly year

This week’s headlines saying 2020 was the worst year for UK excess deaths since WWII are OTT. Adjusted for population, it was actually the worst since 2003. But don’t pretend we don’t have a real and terrible disease to deal with.

The start of 2021 gives us an opportunity to take stock on the Covid-19 pandemic. Few people will have shed a tear for the passing of 2020 – it was an awful year. But how does this pandemic compare to previous years and what lessons can we learn?

Ed Conway of Sky News has provided a useful ‘data dive’ on the full-year figures for England and Wales in historical perspective. In terms of raw death toll, there were more non-military deaths in 2020 – over 600,000 – than in any year since the ‘Spanish flu’ year of 1918. When adjusted for population, the figures look a little more benign. About one per cent of the population died in 2020, the highest rate since 2003.

However, this is not a good comparison because we have had a declining death rate for decades for a variety of reasons, including better living conditions, improvements in healthcare and the decline of smoking. When Conway compared deaths historically to deaths in the previous five years, it is clear that 2020 marked a sharp upward spike in mortality. Excess civilian deaths in 2020 were up 12 percent compared to recent years – something not seen since the middle of the Second World War.

A further adjustment can be made for age. After all, the UK population has been getting older. Conway argues that, in 2020, based on actuarial statistics, instead of a further improvement in mortality, there was a 13 percent decline in age-adjusted lifespan – the worst year since 1929. Moreover, the pandemic is far from over, with an average of over 700 Covid deaths per day at the start of January.

Conway argues that things could have been even worse without the lockdowns. Others would argue that at least some of the deaths that occurred were caused either by lockdowns or the climate of fear generated by the constant discussion of the pandemic. In September, the Office for National Statistics (ONS) reported that “between 7 March and 1 May 2020, non-COVID-19 deaths were 15.3% above five-year average levels for that period” but added that “from then up until 10 July, non-COVID-19 deaths have been 6.0% below the average.”

Looking at ONS death registrations for the period December 28, 2019 to January 1, 2021, there were 614,114 deaths, of which 80,830 where Covid-19 was the main or contributory cause of death. The average deaths for the same period over the previous five years was 539,083. Therefore, there were 75,031 excess deaths. In other words, there were fewer deaths than expected from non-Covid causes. No doubt many of the people who would have died anyway in 2020 were killed by Covid-19. But the big increase in deaths cannot simply be explained in that fashion.

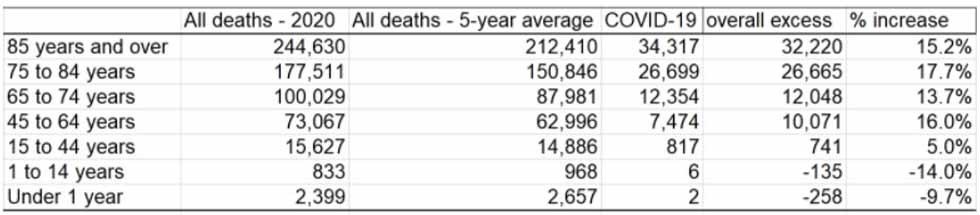

The increase in deaths affected all age groups over the age of 15. Here's some back-of-an-envelope figures, based on ONS data, which indicate that, while the big absolute increases have been among the oldest people, there were significant increases in mortality even among middle-aged people, too.

I'm as sceptical as anyone about the government's narrative across this crisis. But the important thing about scepticism is to be honest about what the data tells us and be open to changing your view. For example, when the UK government attempted to use alarmist forecasts in September – claiming as many as 4,000 people per day could be dying from Covid-19 just a few weeks later – this was scaremongering nonsense that had the effect of undermining trust. But case numbers, hospitalisations and deaths over the past few weeks suggest this pandemic is far from over.

Others seem unwilling to take a hard look at the more recent figures and change their position. Some still cling to the notion that this is an epidemic of false positive tests. But a lot of people have died and the hospitals are exceptionally busy. It is true that there has been year after year of 'crying wolf' about the imminent collapse of the NHS, something which has never happened. At most, less urgent work has been postponed for a few weeks in specific places during particularly bad influenza outbreaks. That has never remotely been seen as justification for the wholesale suspension of our basic liberties.

So it is understandable that some commentators are cynical about the claims being made now, seeing them as justification for authoritarian crackdowns. The ham-fisted approach of police in Derbyshire and Wales in recent days, fining people for perfectly reasonable behaviour within the lockdown rules, shows we should be wary of giving the state more power. I stand by the points made in my previous article for RT – that the negative impacts of lockdowns are discussed too little and are not incorporated into decision-making sufficiently. While lockdowns may exert a short-term downward pressure on the number of cases, the impact is temporary and even this effect may be waning in the third lockdown. The countries with the worst outcomes are often the ones that have imposed the strictest lockdowns for the longest period of time. It seems entirely sensible to discuss alternatives rather than closing down debate.

Vaccinations do provide the possibility of getting out of this mess. But, as I predicted last month, the effect of vaccination programmes has been to reinforce restrictions rather than lift them. The message has been that we should carry on suffering for a bit longer, it'll all be over soon. But even that message of hope has been diminished. Rather than starting to open up society again as soon as the most vulnerable groups have been vaccinated and acquired good immunity – potentially cutting deaths by 80 per cent or more – the noises from government suggest that 'independence day' is being pushed further and further back.

The opposite should be true. We should be asking firmly (but not compelling) the most vulnerable to shield themselves as much as possible. With vaccinations already ramping up to one million per week and likely to rollout faster still in the next week or two, this period of shielding should only last for a few weeks. The rest of society should be allowed to return to a semblance of normality.

Honest, clear-eyed scepticism that avoids dogmatism is more vital than ever in order to keep the pressure on the government. The alternative is to keep lockdowns in place, with all the damage that they do. Last year was bloody awful, let's not make 2021 any worse than it needs to be.

Think your friends would be interested? Share this story!

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.