Reports from America suggesting Beijing is dramatically increasing its number of nuclear weapons have a definite agenda – to raise the appetite for greater spending on the US military. A new arms race will be the result.

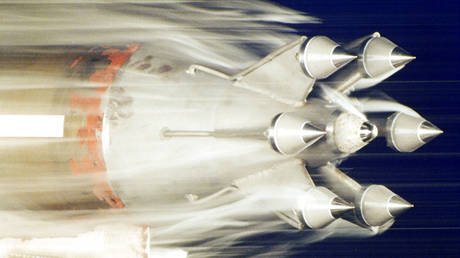

Over the past few weeks, the Financial Times has carried a number of stories based around deliberate leaks and interviews from the Pentagon. It was the FT, for example, that broke the news about China’s apparent hypersonic missile test.

The stories all have a common theme and focus – to dramatically hype up the supposed ‘military threat’ from Beijing, warn of its increased capabilities, and drum up demand for the US to do more to counter it.

The latest story of this nature appeared on Monday. In an interview with the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Mark Milley, the FT reports that the Pentagon is apparently “stunned” that China is dramatically scaling up its nuclear warheads and will have over 1,000 by the end of this decade.

If true, the story is noteworthy because it marks a clear shift in China’s nuclear weapons policy, which for over half a century has been based on the idea of having a minimum deterrent. The timing is significant, too, because it was published just hours before the highly anticipated virtual summit between Xi Jinping and Joe Biden. The article pursues a predictable agenda, with Milley quoted as saying, “We need to act with urgency to develop capabilities across all domains – land, sea, air, space, cyber and our strategic nuclear forces – to address this evolving global landscape.”

In other words, it’s a call for US military spending to be dramatically increased. Little wonder then, that the headline highlights Milley’s claim that China’s apparent nuclear build-up is “one of the largest shifts in geostrategic power ever.”

There is good reason to believe that China is indeed recalibrating its nuclear policy, but not in the way the US says it is. The abandonment of the ‘minimum deterrent’ position comes in response to the shifting geopolitical landscape, whereby the US has attempted to pursue an all-embracing military containment of Beijing in multiple areas on its own periphery.

This includes regularly sailing aircraft carriers up close to China’s territory, pursuing constant military exercises (and encouraging allies to do so too), forming military coalitions against China through the likes of the Quad and AUKUS, increasing arms sales to Taiwan, and so on.

Whilst it might be tempting to describe this build-up as similar to the Cold War nuclear arms race between the US and the USSR, Beijing’s objectives are more limited and specific than amounting to a question of hegemony.

First of all, this is all focused on a specific region rather than having global scope. It is not comparable to the Cold War, where the USSR had amassed nearly 50,000 nuclear warheads by the time of its collapse.

China is not attempting to compete globally with the US – which sustains over 4,400 active warheads – but rather achieve the upper hand in the Asia-Pacific region, with the aim of consolidating its hand over Taiwan and the South China Sea.

Despite this, China has not officially denounced its ‘no first use’ policy and continues to pay lip service to it. This means that unless it says otherwise, these warheads remain as a deterrent, and will not be used in offensive action.

Despite the ‘no first use’ policy, everyone knows the strategic and political considerations of nuclear weapons are based on potential, and influence the balance of power accordingly.

And herein lies the key point which constitutes the “geostrategic power shift” that the article alludes to – as exaggerated as parts of it may be. The intention by Beijing is clear – by building up its nuclear arsenal, China is seeking to nullify the probability that in a war scenario, the US would, under its own ‘first use’ policy, launch or propose a pre-emptive nuclear attack on China to, for example, save Taiwan.

Beijing’s arms build-up serves to negate that potential scenario by raising the stakes to vastly increase the retaliatory destructive power it could unleash on the US or its allies. This kind of consideration could have a significant impact on the policies of surrounding countries, such as Japan or Australia. Because even if Beijing vows not to use a nuclear weapon first, the more relevant question is: Are you willing to engage in military action against a nuclear superpower? Words alone mean little when war begins and the risks become bigger.

While putting together an arsenal of 1,000 warheads is not an attempt to compete with the US head on, it is sufficient to make countries – including America itself – see China in a different light.

This is where China’s regional advantage comes into play. Beijing would like to show that it is capable of taking Taiwan without the US and its allies having the capability or will to respond, giving it the potential to do so without firing a single shot – in which case the ‘no first use’ policy would be irrelevant.

For Washington in particular, this changes the scenario to a question of whether a war against China could ever be won. And this at a time when there are some in Washington who want the US to commit to a war to ‘save Taiwan’. How could it do so in this case?

But it also means the US will respond – as the agenda of the FT article makes clear – and pursue a nuclear build-up of its own. In that case, we must acknowledge that the threat of a new nuclear arms race becomes a very real possibility and is arguably happening already. There is no chance that the US will simply allow China to shift the balance of power – but the reality is that Beijing’s actions are a response to moves by the Americans.

In conclusion, it seems highly probable that China has changed course on its nuclear policy. From keeping a minimum deterrent, it is now said to be pursuing a build-up which will escalate its arsenal to four times its last reported size. This is a strategic response to the ongoing American efforts to contain Beijing, with the goal of making a war scenario a non-starter.

China is not seeking to be a nuclear hegemon on a global scale, but it has nonetheless decided that it needs to show it is a serious player. As the FT article proves, the US will willingly highlight this to push for funds for an arms build-up – and that’s exactly what we’re now getting.

If you like this story, share it with a friend!

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.