Incredibly realistic deepfakes and shoddy shallowfakes reveal quantum leaps in technology that have potential to cause mayhem, but new book ‘Trust No One’ finds time and money are key to keeping a lid on false ‘reality’ – for now.

Back at the dawn of Adobe Photoshop, as a journalist working in the gutter press, my colleagues and I used to exercise our minds over the boundless possibilities to distort the news and have a laugh by mocking up fake images and pegging a story alongside.

The new digital manipulation photography was handy not just in removing blemishes, wrinkles and red-eye from the many topless glamour models who populated the pages of now-defunct Sunday Sport, it was also essential in producing the pictorial accompaniment to one of the most famous red-top headlines in British newspaper history: ‘World War 2 Bomber Found on the Moon.’ And there it was, a Lancaster bomber parked in a crater for all to see. Just prove it was fake.

In top secrecy I commissioned and collected the image from one of the new design houses that had sprung up in London offering never-seen-before digital services to the print industry – at a hefty price. We paid £3,000 for the one black and white pic of a plane on the Moon that nowadays would take a computer-savvy child just minutes to produce and print out on their inkjet.

Not that they would be interested in such Stone Age efforts, when they have apps on their smartphones like Reface, open-source tools like DeepFaceLab and entirely artificial virtual influencers like Aliona Pole that make our deception at Sunday Sport look clumsy, amateurish and decidedly so last century.

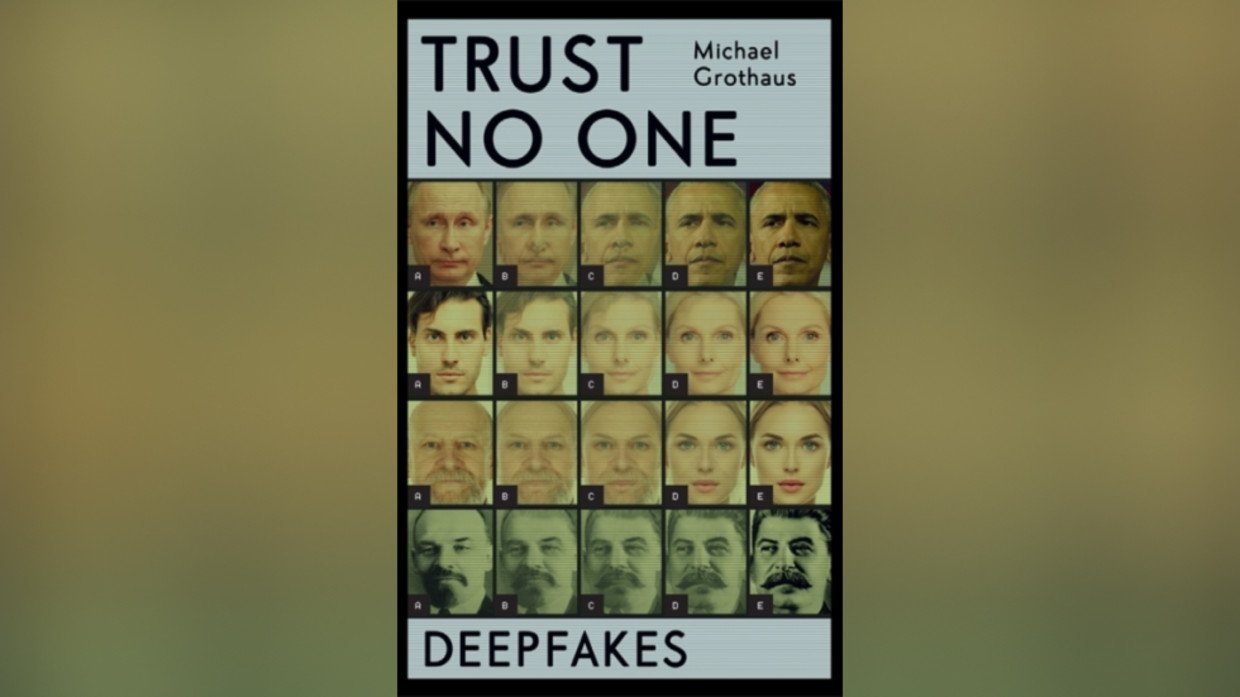

And you’d have to agree. You can load your own selfie on Reface and in minutes turn yourself into The Rock, James Bond or Hannibal Lecter, what’s called ‘fancasting’ yourself into movie trailers with startling realism. It’s addictive fun using algorithms that map your features to those of a Hollywood star. Clever stuff that makes you think maybe journalist Michael Grothaus is right in titling his new book ‘Trust No One: Inside the World of Deepfakes.’

Because he points out that while the computing power of a smartphone limits the resolution and potential of deep (learning) fakes, load up DeepFaceLab on your PC rig and the sky – or maybe the moon – is the limit.

Grothaus looks at probably the most advanced deepfake of them all, the amazing video put together by media artists Francesca Panetta and Halsey Burgund that shows an alternate version of events, titled ‘In Event of Moon Disaster.’ It features former president Richard Nixon apparently reading a speech that was written for him, but never delivered, should the 1969 Apollo mission to the Moon have ended in tragedy.

Using video from a genuine Nixon appearance – his 1974 televised resignation – the two artists had an actor filmed reading the speech and then the movement of his mouth, lips and facial muscles were mapped onto Nixon so expertly that it is impossible to see the seams.

But that was only half the exercise. To pull off the stunt, they also had Nixon’s distinctive vocal delivery analysed and dismantled, sound by sound, so that it could then be laid over the actor’s audio to simulate the long-dead president reading a speech out loud when in reality, that never happened. And it worked perfectly and shows with unsettling authenticity exactly what is possible.

Sure, to produce something this good took time and money – and goodwill. And while individuals might struggle to find the computing power, time and money to effectively turn out something anywhere near the quality of ‘In Event of Moon Disaster,’ there could be bad actors out there, nation states with a mischievous bent, for instance, that could exploit this technology.

What if a seemingly authentic televised news broadcast showed North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un announcing that he had just fired a nuclear missile at Japan? It looks like the Supreme Leader, it sounds like the Supreme Leader, do we have the time to prove it’s not him or should everyone in Tokyo take shelter and wait for the apocalypse or bomb the bejesus out of Pyongyang right now?

Deepfakes make it hard to tell, but they’re expensive and as is the way when someone creates something impressive on the internet, they’ll want to tell everyone about it first chance they have.

As Grothaus finds, even more basic efforts can have a resounding effect. He looks at the work of YouTuber Skitz4twenty who with nothing better to do, created ‘The Hillary Song,’ a mash-up he made using two separate videos, one featuring Dwayne Johnson when he was a wrestler known as The Rock bawdily roasting one of the sport’s administrators, and the other of former presidential hopeful and FLOTUS Hillary Clinton making a speech.

He splices the two together, sometimes sloppily, so it appears that The Rock is insulting Clinton. There. Nothing more. He created what is known as a quick “shallowfake.” Yet more than 3.5 million people viewed ‘The Hillary Song,’ with hundreds of thousands convinced that what they are watching really happened and that The Rock was a committed Republican, despite having implicitly endorsed the Democrats in the last election.

So mischief can be cheap. And nasty. Because like so much on the internet, pornography has inevitably exploited the advances in technology that gave rise to deepfake. Sad fans paste the faces of their favourite Hollywood actresses over those of porn stars and imagine lord knows what while they do heaven forbid. Creepily, it’s young ‘Harry Potter’ star Emma Watson who features disproportionately in this particular output.

And then this can give rise to the creation of revenge porn or even revenge crime, where one person’s visage is pasted over the face of another committing an illegal act and so on and so on. Think of something, find an image of your victim and a target video, then map the two together and hey presto! You’re an evil genius with one less friend.

It’s another of those internet rabbit holes, which even Grothaus finds himself falling down. His book ends with him recounting how he commissioned a deepfake video of his father, who died two decades ago, depicting him enjoying the video technology of a smartphone that was yet to arrive when he was alive. He had his father’s face mapped onto the video of a perfect stranger out walking in a park. It’s a sad, sentimental and harmless indulgence for the author who misses his father, but even he realises there’s something not quite right about inventing this sort of ‘reality’.

It gives rise to the ‘uncanny valley’ effect, which is when the emotional response to an image or a video is struck by something that’s just not quite right. Look at Aliona Pole, the artificial virtual influencer, or the Zoom avatars offered by Pinscreen to be the perfect you for those boring video calls and you’ll immediately see what I mean.

This is an innate filter that most of us seem to possess that, combined with common sense, tells us that something isn’t as it might appear. Sure there are plenty of stooges out there ready to believe anything they see on the internet but, for the time being, the rest of us can tell when we’re having our leg pulled.

For now that is, until technology overtakes us and then, indeed, the default position might well be to trust no one.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.