China’s response to America’s call to back it over Russia’s Ukraine ‘aggression’ is telling

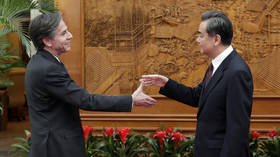

On Wednesday evening, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken phoned his Chinese counterpart, Wang Yi, and lectured him on what he described as “Russian aggression” on Ukraine. The move was an obvious diplomatic stunt from Washington to try and isolate Moscow by appealing to Beijing, seemingly fearful of the growing strategic partnership between the two countries. But Wang wasn't impressed by this insincere cry for help.

Instead, Chinese media reports on the call stated that Wang urged Ukraine to follow the Minsk Protocol, indirectly stated opposition to NATO expansion, and lashed out at the US on a number of issues, accusing it of “interference” in China’s internal affairs, deliberately undermining the Winter Olympics, and demanding that it comply with the One China policy on Taiwan.

Most strikingly of all, Wang said that the US had not changed its China policy at all from that of the Trump administration, accusing Washington of continuing to undermine the bilateral relationship through hostility. In summary, the call was a cold rebuke of American demands.

The Biden administration is attempting to ‘have their cake and eat it too’ in its relationship with China. It wages relentless hostility towards Beijing in a destructive manner, but when a geopolitical issue arises where Washington needs China’s support and dialogue, Washington expects cooperation in good faith, dismissive of the fact that its own behavior makes this impossible. It somehow believes that some shorthand lip service on matters such as Taiwan are sufficient to secure China's assistance, which their policy moves later tend to show the opposite anyway.

This kind of attitude was particularly visible during the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan last year, is the underlying assumption regarding Washington's approach to North Korea, and is apparent here again with Ukraine. While China is not foolish enough to reject dialogue with the US outright, the view in Beijing is one of increasing frustration and is fed up with this behavior, which it sees as increasingly in bad faith, and is less willing to make concessions without driving bargains.

As one noted example, in November last year, Chinese President Xi Jinping held a summit with US President Joe Biden. From China's perspective, this meeting was designed to stabilize ties and sway the US away from the aggressive anti-Beijing Trumpian policy. In practice, the summit achieved nothing, and Biden immediately responded afterwards by entity listing scores more Chinese companies and voicing support for a bill banning all imports from Xinjiang on the premise of forced labor.

This chaotic and hypocritical approach to US diplomacy means Beijing now increasingly sees good will engagement with the US as a waste of time. If the US wants anything, it must be conditional on respecting China’s core interests, which it continues to undermine. Therefore, Wang took the opportunity to hit out at Blinken on a number of issues which were not on his agenda, effectively seeking to make any presupposed consideration of America’s position conditional: including non-interference and on Taiwan.

It should also be plainly obvious that China is not going to allow a wedge to be thrown into its relationship with Russia when both countries see the antagonism from the US as mutual. Wang denounced the “Cold War mentality” surrounding Ukraine and stated that “regional security cannot be guaranteed by strengthening or even expanding military blocs.”

Whilst normally this discourse is reserved for describing attitudes towards China, here it is applied directly in reference to Russia, in particular the longstanding western discourse of a threatening Russian state which is apparently itching to unleash military conquest on Europe. While Beijing will do little more than urge stability and peace, it nonetheless requested Kiev follow the Minsk Protocol – the 2014 agreement to end fighting in the Donbass region.

This, combined with the earlier comment about opposing “military blocs,” shows that China is not “impartial” on this matter and has tilted in Moscow’s favor, a clear indication that China itself is indirectly opposing the expansion of NATO. Blinken didn’t achieve any of his objectives from the call and it demonstrates how the US is struggling in dealing with Moscow and Beijing simultaneously.

This shift reflects China's new foreign policy trend, that it is prepared to give more backing to states also facing trouble with Washington than it was previously, such as with Syria, North Korea, Cuba, Eritrea, Iran and others.

This single phone exchange illustrates how China has shifted from being more willing, cautious, and subservient in following the US on certain geopolitical issues, to placing more emphasis on its own preferences in a careful, yet clear, way.

The US cannot have its cake and eat it too – it can’t get cooperation from China on issues like Ukraine while also aggressively confronting it at the same time. Beijing is making it clear that this kind of relationship is no longer viable. If the US wants to engage with China, Beijing is setting a very high price for it, and the Ukraine saga is an illustration of that.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.