European nationalism enjoying good times

Not since the 1930s has nationalism enjoyed the political influence and traction in Europe that it does today.

All across the continent we are witnessing nationalist parties and movements – extreme and not so extreme – having the kind of impact they could only ever have in a time of economic recession and convulsion.

Regardless of the form it takes – whether extreme or not - a political ideology rooted in ethnicity and nationality, cultural differences, and not forgetting religious differences, is eminently regressive. Indeed, just as it was in the 1930s, nationalism across Europe in the second decade of the 21st century has emerged as a dangerously divisive and reductive reaction to the deleterious impact of global economic factors, feeding on the fear produced by the economic insecurity being suffered by millions of people as a consequence.

Economic roots

Economic upheaval produces political upheaval, providing the opportunity for radical solutions to seemingly intractable crises.

This was the terrain out of which fascism grew 80 years ago. The Great Depression had delivered millions into the arms of destitution and unemployment across a European continent that had yet to fully recover from the catastrophe of the First World War. As with the economic shock to engulf the world in 2008, the Great Depression of the 1930s started in the United States with the stock market crash of 1929, arriving on the back of a boom that had been fueled by an unsustainable level of consumer debt, reckless lending in poorly regulated markets, and lack of long-term investment. The result was a global slump which proved a godsend to hitherto marginal political figures such as Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler, along with the movements they led.

Russia had already had its radical overhaul with the onset of the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. But here it should not be forgotten that the Bolsheviks weren’t the only radical political party vying for support and power in Russia at the time. Reactionary and ultra nationalist groups and parties were also emerging in Russia during the chaos that beset the country in the midst of the First World War. Fortunately for Russia, and the world, it was the Bolsheviks who emerged triumphant in the political struggles of the period, though not without huge suffering and hardship.

By the early 1930s, attempts to replicate the Bolshevik Revolution across Europe had failed. In their place ultra nationalist and fascist alternatives had taken root, offering the masses a suitable scapegoat to blame for their poverty and hardship in the shape of ‘the other’ – Jews, gypsies, Slavs, communists, trade unionists and so on.

In their modern incarnation, nationalist movements and parties throughout the continent, with the exception of Scotland, have succeeded in legitimizing racist views and revulsion of multiculturalism and immigration. In its most extreme form this has manifested in organized violence against people deemed ‘untermenschen’.

The growth in support for Greece’s Golden Dawn, for example, is indisputably a product of the collapse of the Greek economy and the tsunami of mass anger and rage it produced in the country. In 1996, Golden Dawn received a total of 4,537 votes in Greek parliamentary elections. In 2012, they received 440,000 in the country’s May elections. The difference between 1996 and 2012 was not Golden Dawn, but the change in the country’s economic and social conditions.

In the UK, the rise of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) has propelled its leader, Nigel Farage, to mainstream prominence and respectability. This is despite the party's near total fixation on leaving the EU and halting immigration as a remedy to the nation's problems. Regardless, UKIP’s alarmist political message vis-à-vis both has gained traction with a growing number of voters in England, many of them disenchanted anti-European conservatives, but also increasingly natural Labour voters living in low income communities hit hardest by the recession and the austerity measures implemented by the British government in response.

Recent opinion polls indicate that UKIP is set to emerge from the upcoming European elections as the UK’s largest party in the European Parliament. This would be an astonishing endorsement of a party whose political program would not look out of place in the England of the 18th century - that mythical green and pleasant land immortalized by William Blake in his popular poem Jerusalem.

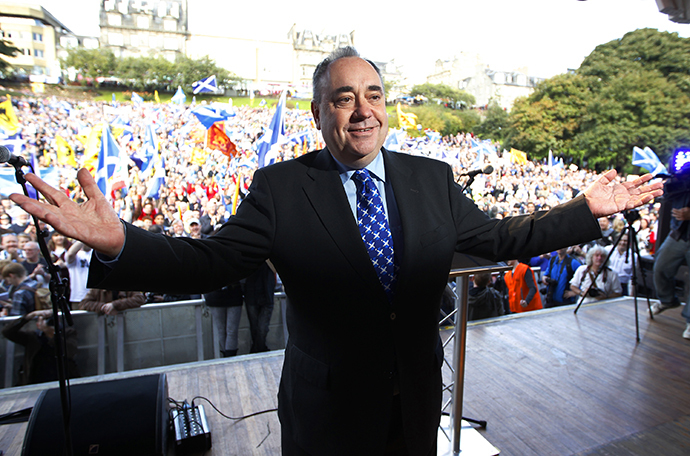

North of the border in Scotland, the Scottish National Party (SNP) approaches the referendum in September to determine whether Scotland separates from the UK more confident of victory than it is entitled to be given the vacuous political vision it offers. As with UKIP in England, the SNP has seen its fortunes improve on the back of the economic crisis which engulfed the country six years ago and the Tory led coalition government’s austerity program of draconian spending cuts in response. Making the resulting pain even harder to take is that with just one elected MP the Tories have no support in Scotland. This has served to expose a democratic deficit, sharpening a sense of collective grievance on the part of a growing number of Scots, benefiting the SNP.

The other key factor contributing to the upturn in the fortunes of the SNP has been the political degeneration of the Labour Party over the past 20 years in a process which began under the leadership of Tony Blair. In 1994, Blair and the coterie of political opportunists who supported him gave birth to New Labour, turning the party of Keir Hardie, Nye Bevan, and Tony Benn from a party of the millions into a party of the millionaires. It was a victory for Thatcherism and the free market nostrums it espoused, discarding in its wake the needs and hopes of the Scottish working class, who now found themselves without political representation worthy of the name.

What are the bounds?

Underpinning both UKIP’s and the SNP’s political programs is the belief that erecting a border equates to progress. Within those parameters, however, the politics of both are radically different. The SNP and its supporters have embraced what they describe as ‘civic nationalism’, wherein it is people living in Scotland not Scottish people per se who are the determining factor in their priorities. The SNP maintain that their vision for Scotland is modern, forward-thinking, and progressive. That said, as with every nationalist project or movement, the SNP’s politics obscures rather than illuminates the only divide in society that matters – economic and social class – thus rendering them regressive at heart.

Across the rest of Europe nationalist parties have seen their fortunes improve over the past five years of an economic recession caused by the failures of neoliberalism and the failure of the political mainstream to relegate this extreme variant of capitalism to history. Whether it is the Catalan separatist movement in Spain, Italy’s Northern League. Allianz fur Deutschland in Germany, nationalism is on the rise across Europe. Moreover, as we have seen, it exists on a spectrum which runs from the ultra-nationalism and/or and neo-Nazism embraced by Golden Dawn in Greece, Jobbik in Hungary, and Svoboda in Ukraine, to the more palatable variation represented by the SNP in Scotland.

Some have compared the SNP to Ireland’s Sinn Fein. It is a false comparison, however. Sinn Fein has a distinct history and development compared to the SNP in Scotland on the basis that the Irish people suffered the kind of oppression commensurate with its centuries-long status as a British colony, while Scotland was a colonial partner of England's and played a key role in forging the British Empire. This difference is reflected in the politics of both parties today – specifically Sinn Fein’s refusal to take up its seats in the British Parliament and the SNP’s desire to retain the British monarchy as head of state should Scotland vote for independence.

The legendary Scottish trade union leader Jimmy Reid once described nationalism as a political doctrine capable of keeping a baby alive in an incubator or frying a man in an electric chair. The determining factor in both cases comes down to the specific ends nationalism serves. In the 1930s those ends were expressed in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. Those who believe that nothing like it could happen in Europe again have failed to learn the lessons of history. Indeed, as the German playwright and communist Bertolt Brecht warned with regard to fascism at the end of the Second World War: “The womb from which this monster emerged remains fertile.”

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.