Khodorkovsky: Myths, hagiography and the pardon

President Vladimir Putin’s decision to pardon disgraced oligarch Mikhail Khodorkovsky was indeed a bombshell.

Having been a witness of – and wrote extensively about – the “Yukos affair,” I fully expected Khodorkovsky to serve out his full sentence, then to slowly fade away.

How to explain Putin’s political calculus? Western media and the world of punditry immediately explained Putin’s decision as a mixture of “a man at the pinnacle of power” who could afford to do so, as well as an attempt to “clean-up” Russia’s human rights record before the Sochi Winter Olympic Games. Both explanations are mildly interesting, but neither is compelling. Putin does not have to prove anything to anyone.

Khodorkovsky was not a prisoner of conscience – he was a criminal who would have been sentenced to life in other jurisdictions for the crimes he committed. Khodorkovsky can hardly have been called a businessman either – he, like other oligarchs during the 1990s, stole, extorted, and even possibly ordered murders when making empires from looted state property. He was also a political fraudster – buying political influence from virtually anyone who would take his dirty money. It was only in prison did Khodorkovsky “find religion” in an attempt to rebrand himself as a man of the people and supporter of democracy.

Khodorkovsky and his PR machine created myths too. Khodorkovsky was never a real threat to Putin’s political power and Putin never feared him (and probably never will). Before his arrest, trial, and imprisonment, Khodorkovsky expressed little interest in being elected to office.Though there is overwhelming evidence he did everything in his power to capture the state for personal gain. And this is what was at the heart of the “Yukos affair.”

Not only did Khodorkovsky become Russia’s richest man, but he also intended to cash-out and/or make himself even richer (and at the expense of the Russian state and people). No one can deny Khodorkovsky had ambitions. His ambitions became hubris. First, he wanted to sell Yukos to Texas oilmen. Second and against Russian law, he wanted to build a private pipeline to export energy. (Under Russian law, the state has the monopoly right to export energy). Putin, as head of state and protector of the country’s sovereignty had no choice – Khodorkovsky and the other oligarchs had to be stopped.

After being elected to the presidency in 2000, Putin made it clear the oligarchs were to stay out of politics and pay their fair share of taxes. This was the background to what is called Putin’s “Oligarch Wars.”

Khodorkovsky ignored Putin’s warnings and threats at his own peril. Western media and paid apologists in the service of corruption claim Khodorkovsky is a victim of arbitrary prosecution and persecution.

This is fantasy. The fact is Khodorkovsky willingly put himself straight and center in Putin’s sights. Taking on Khodorkovsky, the Russian state was saved from what could have easily turned into a de facto oligarch coup. It was at this time the other oligarchs understood that Putin was not to be taken for granted. Instead of an oligarch coup, the remaining oligarchs either fled or became – to use Putin’s words – highly paid state workers working in the interest of the state.

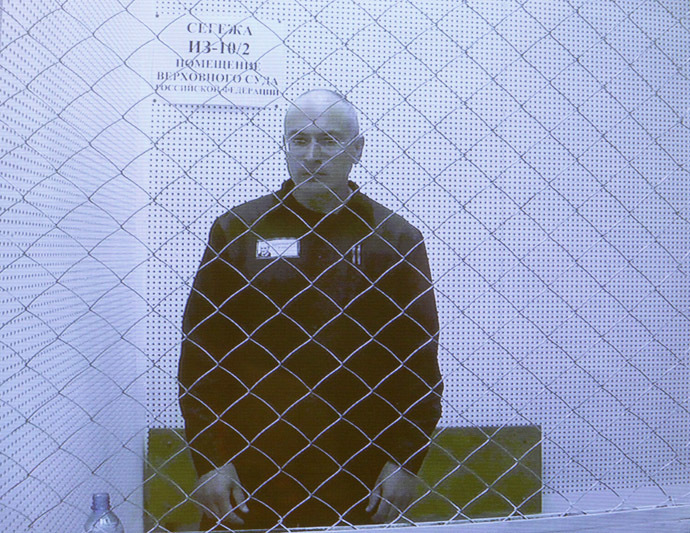

Western critics claim Khodorkovsky did not receive a fair trial and that his trials were politically motivated. That is not the opinion of the European Court of Human Rights. In the Court’s judgments Khodorkovsky was guilty of massive tax evasion for which he was justly convicted and imprisoned. In another judgment the Court found that there were no grounds to suppose a political motivation to his case distinct from the charges that were brought against him. Alas, Khodorkovsky’s hagiographers never miss a chance to omit or overlook inconvenient facts.

Another myth about Khodorkovsky is public perception of him. For a small number of Russian liberals and of course the entirety of western mainstream media, Khodorkovsky is a saint. Miraculously, Khodorkovsky is deemed the conscience of the nation having martyred himself in front of Putin’s “authoritarian” throne.

The average Russian thinks differently. Khodorkovsky is a name and person associated with the

past – and an awful past at that. Khodorkovsky is no hero to the millions of Russians who saw their lives turned upside down. They witnessed a small number of greedy and heartless individuals rob them and then to almost destroy the state down to its very foundations.

Khodorkovsky and his fellow oligarchs had no tears when the lives of millions were destroyed.

Now on to the pardon: Putin could have pardoned Khodorkovsky years ago. Foreign public opinion has never been part of his political calculus – and he cares even less about the low-octane thoughts and words of western media pundits. Had Putin granted a pardon a year ago, two years, or even five years ago, basically the same nonsense that is written today would have been heard.

Russia’s human rights record has always been and probably will continue to be a reason to criticize the Kremlin. But it does not change Kremlin behavior (and won’t in the future).

As for the theory Putin can afford the pardon because he feels powerful enough to do so – well he has strong and consistent public opinion support (even as the economy has hit a rough patch). To date, Putin has never really been forced to do anything that he was against.

Political opposition to Putin’s governance is on the rocks – and this probably won’t change anytime soon. Russian liberals bickering among themselves long ago become a national spectator sport.

Putin pardoned Khodorkovsky because the former Yukos head was one of many eligible for early release under a general amnesty law– along with the political action group Pussy Riot and the Greenpeace 30. There is nothing special about Khodorkovsky beyond his greed and hubris. Putin apparently believes Khodorkovsky served enough time thinking about both.

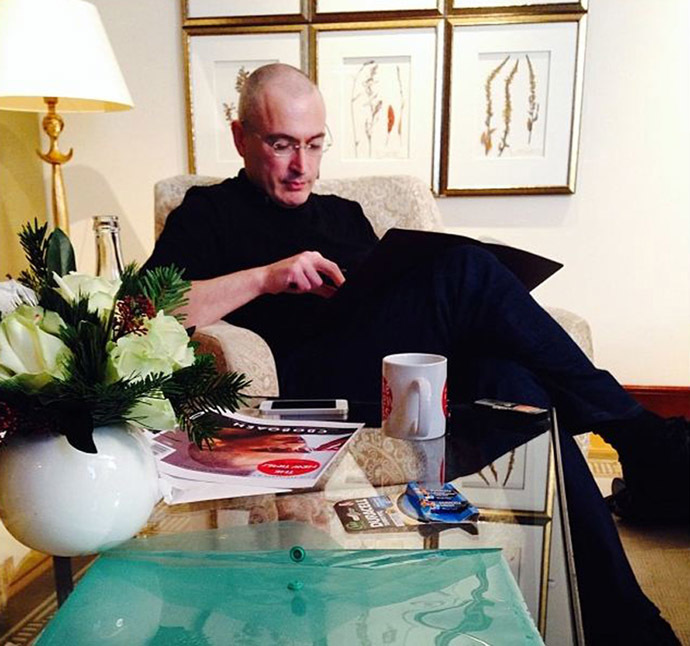

What happens now is an open question. We should assume Khodorkovsky still has significant funds stashed away in foreign bank accounts. Now we will see if Khodorkovsky has learned anything from his criminal past. There is no meaningful interest in him from the average Russian.

The best way for him to rehabilitate himself would be to simply fade away.

Save this space!

Peter Lavelle is host of RT’s “CrossTalk” and “On the Money.”

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.