Turkey sprawl: Only real model of democratic Islam is rapidly crumbling

At the end of this week there will be a very special rendezvous in Turkey.

The local elections March 30 will decide not only the new mayors of Istanbul, Ankara and Izmir, among others: after the current season of scandals and rampant authoritarianism, it will be a crucial test to assess whether Prime Minister Erdogan is still able to play the old game. The dream of a moderate Islamism ‘alla Turca’ is indeed crumbling away. To understand how we got to this point, we have to take a step back.

Once upon a time, there was the Demo-Islamic New Wave with the round face and the moustache of Erdogan. Many analysts believed they were seeing the avatar of the old Western Demo-Christian party in Janissary disguise: religion ‘ma non troppo’, always at the center against the opposite extremisms.

Turkish businessmen started to uncork bottles of (non-alcoholic) champagne: the AKP, the Islamic party, had some little manias, like introducing the headscarf in universities and to ban every drop of wine, but it was bowing ecstatically in front of the market’s dogma.

For the Islamists, the economy’s numbers were turning in medals. All pious and honest people, not like the old Kemalist, secular cynics always expecting a little help to grease the gears of bureaucracy.

Foreign Minister Davutoglu brilliantly invented a long term politics that someone called neo-Ottoman. The first corollary was: zero problems with our neighbors. Friends of Iranians and Israelis alike. At home, they opened a promising dialogue with the Kurds, until recently still called ‘Turks of the mountains’. The result was that the long lists of dead soldiers in the war against the separatists almost disappeared. When in 2011 the so-called Arab Springs exploded, Turkey was already a model ready to be exported.

With the Arab uprisings, however, the perfect image began to melt away. A model cannot afford ambiguities, but Erdogan was very wavering about Libya and Egypt. Gaddafi’s Libya meant a lot of dollars, the Egypt of Mubarak was on the verge of signing a huge free trade pact with Ankara: business and revolt did not get along.

Embarrassed by the loyalty due to his NATO partners, in Libya Erdogan tried at the last round to propose himself as an unlikely mediator and in Egypt jumped on the bandwagon of the Muslim Brotherhood. The alliance with the Brothers was cemented by the beginning of civil war in Syria. Turkey became the main military rear line of the international cartel against Assad.

Farewell Zero Problems with Our Neighbors. The good relations with Iran, the principal supporter of Damascus, collapsed with Syria. The deadly Israeli assault on the Mavi Marmara, the ship of pro-Palestinian Turkish activists trying to break the blockade of Gaza, led Ankara to break relations with Israel. America was watching the old ally with increasing apprehension, which, however, in the case of Syria remained essential. The willingness of Ankara to purchase some Chinese missiles has been the final irritation for Washington and NATO.

Problems at home

At home, Erdogan got rid of the generals’ power early. The Army used to be the true masters of Turkish politics (three coups and two half-coups from 1960 to 1997) with a series of shady trials for conspiracy. The ‘diversity’ of the Islamic party was beginning to crumble, the sin of corruption unexpectedly found breeding ground among the pious Islamists. The government showed a growing annoyance with the democratic rules, especially against journalists, who never bowed enough.

The country started to boil over and divide into two opposing camps. Last year, the people’s protests to save Gezi Park, an ancient Ottoman garden in Istanbul, from being cemented over, led to a series of protests across the country, brutally crushed by police. The result was 11 people dead and over 8,000 injured.

In this atmosphere, the rupture grows between Erdogan and his crucial ally, Fethullah Guelen, a former Turkish Imam retired in the Holy Land of Pennsylvania. The movement of Guelen (to tell the truth he has just explained that it is not a movement but a network...) popularly called Hizmet (volunteer services) is a moderate Islamic organization, active throughout Asia to Xinjiang in China. Some observers, such as the former FBI translator Sibel Edmonds, say that it has deep ties to the CIA.

For the American Imam, Erdogan was guilty of having broken off relations with Israel, but the last casus belli was the proposed closure by the government of the University prep schools, controlled by 30 percent from the Islamic network. Hizmet has legions of members in the police, the judiciary, the Turkish bureaucracy, in the same majority party: now the prime minister has discovered that it is ‘a parallel state’.

As it happens, shortly after the political divorce, the police discovered a huge corruption scandal involving several sons of AKP ministers. More than a plot it seems like revenge. Investigators began to perceive some strange traffic that before was apparently out of their radar. The reaction of the sultan was furious: 10,000 policemen and magistrates where transferred, the judicial power was crushed under the heel of political power.

The (allegedly) most explosive tapping arrived in December: like a script from a Scorsese Mafia movie, Erdogan and his son, Bilal, speak about hundreds of millions of euro and dollars to be transferred from the family houses, before someone decides to go and take a look around. Bilal burst out at one point: "We still need to get rid of another 30 million euro." A really tough job.

A furious Erdogan said on TV that it was a plot to smear him. The Western media was cautious; the BBC noted that the voice of the leader in the wire-tapping was weak and uncertain, not peremptory as usual. The very fact that the prime minister made a rhetorical joke about the next possible leak of tapes about sexual conversations (excusatio non petita, accusatio manifesta, said the Romans: ‘an unprovoked excuse is a sign of guilt’) has thrown the Turkish public opinion in a frantic wait for the new tapping.

Locked inside his disdain for the ‘conspiracies’, Erdogan has just made another terrible mistake by expressing not a word of regret for the death, a few days ago, of Berkin Elvan. Even worse, when he finally chose to speak, he said: "The boy's death has not hurt the economy."

Berkin was a 15-year-old boy, who was going to buy some bread in the turbulent days of clashes in Istanbul’s Gezi Park. A tear gas canister smashed his head; he remained in a coma for nine months before his death. To make the story more disturbing is the fact that the guy was an Alevi, i.e. that he belonged to a Shiite minority. Erdogan has often talked offensively about Alevis, letting it transpire that he does not consider them Muslims.

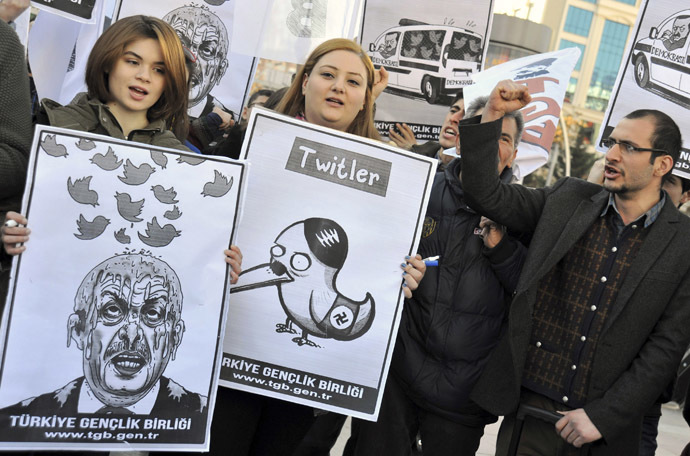

All a-Twitter

Erdogan’s latest show of strength was to try to ban Twitter in Turkey, one of the more effective sources of criticism in his regard. Western media didn’t believe their eyes: an occasion to show themselves as paladins of free speech. Even President Guel had to break his silence and declare: “I hope that the ban will not last.”

“Erdogan's authoritarian tendencies have been evident for a long time,” says Jeremy Salt, history professor at Ankara Bilkent University, author of one of the best books on the modern history of the Middle East, ‘The Unmaking of the Middle East’, “but they have accelerated since leaked conversations last year implicated the sons of senior ministers, and ministers themselves, in wide-scale corruption. By interfering with the internet and taking direct control of the judiciary, as he did last year after the Gezi Park protests, Erdogan is accusing outside forces, and an assortment of internal enemies, of trying to damage Turkey through their attacks on him. Local elections are due on March 30, and the tempo of political events can be expected to be maintained until then. These elections will be a pointer to national voting tendencies but whenever it happens, how it happens and how long it takes, it is clear that the Erdogan era is drawing to an end. The country is now so deeply polarized between those who love Erdogan and those who can't stand him, that it is equally clear that it cannot heal as long as he remains in power.”

Economics Professor Buhran Senatalar, of Instanbul Bilgi University, thinks the same, that the danger is the polarization of the country.

“In Turkey the rule of law itself is in danger. During its rallies, the majority party is using very aggressive and violent language against every kind of opposition. We are bound to a risky polarization between the ones who stand by Erdogan and the others. In the coming elections the government AKP party will consider maintaining 40 percent of the vote as a victory. The great game is between the three big cities of Ankara, Izmir and Istanbul. The polls are saying that Izmir is in the hands of CHP, the social-democratic party of opposition, Istanbul is in the middle and Ankara is very disputed. If the CHP reaches 30 percent it will be a victory. If the AKP goes below 40 per cent, Erdogan will have many reasons to worry,” he said.

“(Erdogan) is not a man without resources,”wrote Henri J. Barkey, professor of International Relations at Lehigh University. He is quite capable of engendering a crisis of sorts, international or domestic, to distract attention and to rally the troops around him. It is also possible that, barring a manufactured crisis, serious reversals in the municipal elections - including the possible losses of Istanbul, his home base, and Ankara, to the opposition - will provoke a move against him within his own party. Already some in the party are secretly hoping that President Abdullah Guel, also a founding member of AKP, will intervene.

“There is no question that Erdogan is in a fight for his political life, but the ground is rapidly shifting under him. The crisis is taking a toll on the economic life of the country. No amount of bombastic recriminations against real and imaginary enemies can undo the momentous damage done to his and Turkey’s reputation, the rule of law, and confidence in sound crisis management - all necessary ingredients for a country to move ahead in a globalized world.”

The big danger now is that Erdogan chooses to embrace a political adventure to try to distract attention from his scandals. The growing tension at the Syrian border, with a Syrian jet just shot down by Turkish Army and the constant support of Turkish artillery to the rebels near the border, are not a good sign.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.