What could Ukraine learn from South Africa?

One year on from the death of Madiba - Nelson Mandela - South Africa still has lessons for other countries about political reconciliation, and particularly for right-wing anti-Russian nationalists in Ukraine.

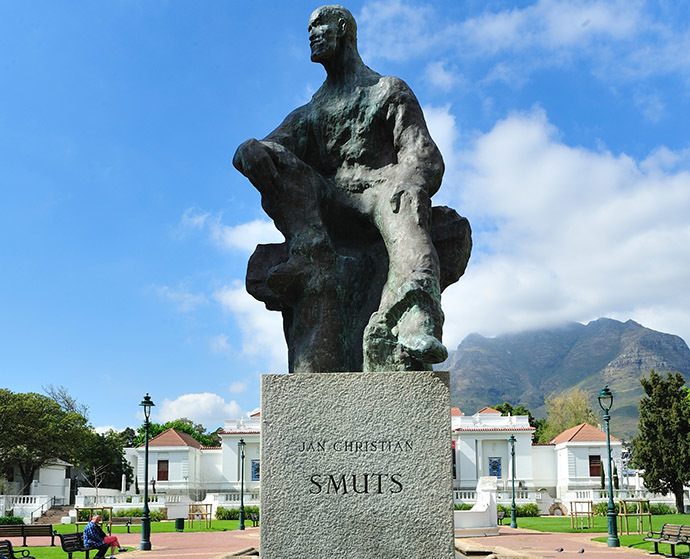

It’s a warm and sunny day in Cape Town and we’re standing in front of the statue of Jan Smuts, the former Prime Minister of South Africa

Smuts is a controversial figure among South Africans, our guide Errol tells us. On the one hand he was a racialist who believed in the superiority of white people and who supported segregation. On the other hand, he was a nature lover and conservationist who did much to protect and preserve South Africa’s amazing flora.

Seeing the statue of Smuts in the centre of Cape Town got me thinking. Here was a monument to a man who thought the majority of people in his country were inferior beings- yet it is still standing. Yet in Ukraine we’ve seen statues of figures associated with the past e.g. Vladimir Lenin, toppled and smashed up with sledgehammers - and such vandalism cheered on by “democrats” in the West as a victory for “freedom.”

Do anti-Russian Ukrainians have more cause to be angry than black and “colored” South Africans?

To answer that let’s remind ourselves of how non-white South Africans were treated during the period of white minority rule. The system of racial segregation did not begin in 1948 with the election of the pro-apartheid National Party, but much earlier. The 1913 Natives Land Act for instance set aside just 8 percent of the land for black people - who made up over 75 percent of the population, while the most fertile land was reserved for whites.

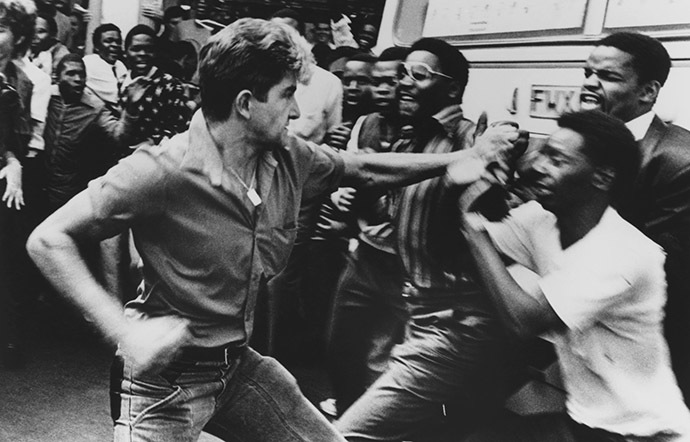

Skilled jobs were reserved exclusively for whites, and laws restricting the movement of black people were established. Blacks were herded like cattle into overcrowded townships while whites enjoyed the best parts of town.

The official introduction of apartheid in the late 1940s only took things a stage further. Pass laws - which prevented black people from travelling where they wanted - were strengthened and the Separate Amenities Act created separate beaches, swimming pools, schools and even toilets.

We can talk about the killings of opponents of apartheid, like Steve Biko, who was bludgeoned to death by the security police in 1977, and the large numbers of people detained without trial and tortured by the authorities under apartheid. We can talk about the 3 million or so people who were evicted from their homes on account of their skin color. We can talk also about the humiliation that non-white people in South Africa experienced in their everyday lives.

By any objective assessment, if we look at the period following World War Two to the early 1990s, the non-white population of South Africa undoubtedly suffered more under apartheid than people in Ukraine- or indeed in Poland or any of the other Eastern European countries under Soviet tutelage. They had far less freedom - and were far more oppressed.

But while the crimes of the communist era are heavily played up, with new books on the subject given maximum publicity in elite media, the oppression and ill-treatment that black people suffered at the hands of white minorities and colonialists in Africa is routinely played down.

As Seumas Milne put it in a 2002 essay entitled ‘The Battle for History’

“Perhaps the most grotesque in the postmodern calculus of political repression is the moral blindness displayed towards the record of colonialism. For most of the last century, vast swathes of the planet remained under direct European rule, enforced with the most brutal violence by states that liked to see themselves as democracies. But somehow that is not included in the third-leg of 20th century tyranny, along with Nazism and communism.”

The worst atrocities in the colonial era in Africa occurred in the Congo, carried out by the forces of Leopold, King of the Belgians.

As I note in my new book ‘Stranger than Fiction:’

“King Leopold’s bloody rule of terror in the Congo cost the lives of around 10 million people. It was one of the greatest crimes in history- but it’s one that tends to get overlooked in comparison with other horrendous crimes which followed in the 20th century.”

The western elites, while keen to remind us of the crimes of communism, a political ideology which poses an obvious threat to their financial interests, are less keen to remind us of the deaths caused by colonialism in Africa and elsewhere, because as Seumas Milne rightly points out - they want to legitimize the new “liberal” imperialism of the 21st century - one which we saw in action in Africa with the NATO bombing of Libya in 2011.

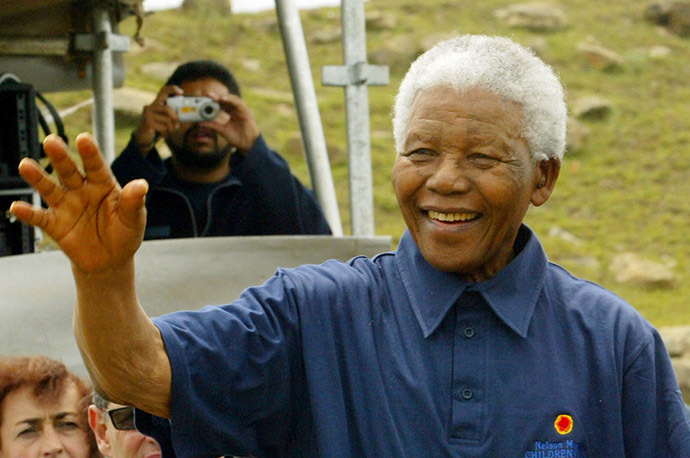

Getting back to South Africa, it was men like the great Nelson Mandela, and that wonderfully inspirational man of peace, Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who set the tone for the country’s post-apartheid democracy. Mandela who spent 27 years in prison under the old regime was a man who certainly had plenty to be angry about. Yet his address to the people of Cape Town when elected as President in 1994 was totally lacking in bitterness. “We place our vision of a new constitutional order for South Africa on the table not as conquerors, prescribing to the conquered. We speak as fellow citizens to heal the wounds of the past with the intent of constructing a new order based on justice for all,” Madiba said.

A Truth and Reconciliation Commission, headed by Archbishop Tutu was set up, which had the power to give an amnesty to those who confessed their crimes.

As part of his campaign to build bridges with the Afrikaner community, Mandela famously put on a green Springbok rugby jersey at the 1995 Rugby World Cup. Rugby is the sport of the Afrikaners in South Africa and by putting on that jersey Mandela was doing his best to bring his nation together.

The contrast between the statesmanlike Mandela, trying to heal wounds between different communities in his country and the belligerent, vicious anti-Russian stance of politicians in the west of Ukraine could not be greater. Mandela talked the language of reconciliation; the Ukrainian politicians talk the language of hate and war.

But Mandela, a man who suffered enormously under apartheid had

far more cause to be bitter than anti-Russian Ukrainian

politicians, or indeed anti-Russian Polish politicians, who we

hear so much of.

It’s not just lessons on the politics of reconciliation that we

can learn from modern democratic South Africa. The country’s

progressive foreign policy is also commendable.

The day we visited Pretoria and saw the beautiful sandstone Union Buildings, the Palestinian President, Mahmoud Abbas was in town for a state visit. Palestinian and South African flags were flying side by side in the street.

“Today is a historic and important day for South Africa and I am very pleased that President Mahmoud Abbas accepted my invitation to undertake a State Visit to South Africa.” declared South African President Jacob Zuma. “The people of South Africa and Palestine have a strong bond built in the trenches of struggle. We want to build even stronger relations and cooperation based on that historical relationship,” he went on.

South Africa is a member of BRICS, (it hosted the 2013 BRICS summit) and doesn’t let the US, the pro-Israel lobby, or anyone else tell it who it should or shouldn’t be friends with, and which causes it should champion.

Again, the contrast with Ukraine, and other US satellite states in Europe, could hardly be greater.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.