The Fukushima disease: Creation of virtual world based on radioactive reality

Visiting Tohoku region of Japan for a second time in four years brings a variety of evocative emotions to the surface after witnessing the wrath of nature combined with the man's attempt to defy it.

While human dimensions of the catastrophe are present now as much as then, there is a complete change in the Japanese zeitgeist when it comes to dealing with the disaster's aftermath.

The area around Haranomachi JR station in Fukushima Prefecture is a de facto entry gate to a recently declared safe area that was closed to the outside world until recently. Despite continuous assurances from both municipal, prefectural and national governments that the area is safe to go back and live, the majority of people under 40 with young kids are decidedly against moving back. "I decided to stay here as I have no place to go but my sister with her kids is not coming back here," said Setsuko-san as she packed my groceries in the local store. "Despite all they are all telling us nobody believes it and besides many people already have their lives somewhere else so there is no use to start it here again. Just look at the town and see for yourself if there is anything to go back to," said Setsuko-san.

The two kilometer walk from Haranomachi station to the Minamisoma City Hall leads through rows of dilapidated businesses, many of which are shut down or on the way, judging from lack of customers in them. The city itself has regrouped in an attempt at a comeback, a far cry from March 2011 when its mayor Sakurai-san [Mayor Katsunobu Sakurai] announced that people had been "abandoned" by the national government in the wake of orders for all remaining residents to stay in their homes despite raising radiation from the Daiichi Nuclear Plant, 16 miles away. The city produces regular monitoring reports of radioactivity from 10 locations around town with Geiger counters placed in public spaces for residents and visitors to check their daily intake.

"We are in a difficult position that we made ourselves reliable on nuclear energy first and then were hurt by it," said a local city employee who asked to remain anonymous as he was not authorized to talk to the media. "Many people here had good jobs and good lives and when the nuclear accident happened this came to a complete halt,” he said. The city's website now is very optimistic in its proclamation of moving forward without nuclear power, despite the central government's move to the contrary. The government in Tokyo has decided what is best for the citizens of Minamisoma and all of Japan.

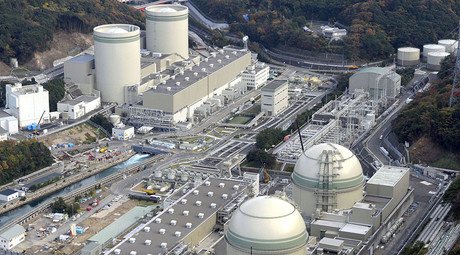

Furthermore, nuclear power is back in charge as if it never left. Nationalist Prime Minister Abe Shinzo's administration is another one anointed by "kempatsu mura" - "the nuclear village", power and money complex that has been a steady fixture in the history of modern Japan. In 2012, Tokyo's Waseda University researcher Tetsuo Arima disclosed declassified CIA documents dating to the 1950s. It was revealed that the long time kingmaker of Japanese politics, Matsutaro Shoriki and head of the country's most powerful Yomiuri Shimbun media empire, worked hand in hand with the CIA to popularize nuclear energy as way for the future. Despite its peaceful angle and spin thrown onto the Japanese public that was still traumatized within a generation of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, Shoriki insisted the way to a successful future would have to include Japan's nuclear armament. Regardless of the existing US nuclear umbrella over Japan in the form of defense treaties and US bases, the thought of a "made in Japan" nuclear capability has been a wet dream of the Japanese political establishment ever since. In 2012 before becoming a defense minister, Satoshi Morimoto stated he viewed the nation's nuclear power plants as a deterrent against foreign attack, apparently because they made neighboring countries believe Japan could produce atomic weapons quickly if it wanted to. That is despite the fact of Fukushima's meltdown eight months earlier and its own government's moratorium on nuclear power in time he made his statement.

READ MORE: Record radiation at Fukushima power plant could kill person in under 1 hour – reports

In the 2012 book "Fukushima and the Privatization of Risk" by Majia Nadesan, Professor at Arizona State University, the convoluted story behind the long road to the Fukushima disaster was revealed contrary to the "safe and bright" future narrative sold to an unwitting and gullible Japanese public. In 1997 an explosion at the Donen reprocessing plant resulted in radiation being released and largely covered up by officials in charge. In 1999, the Joyo nuclear reprocessing plant explosion killed two workers and released huge amount of radioactivity into its surroundings, prompting the Japanese government to get temporarily serious in its supervisory role. "Actually now it is much worse since the Fukushima disaster as the nuclear industry feels it is completely in charge. For example, one thing nobody talks about is a complete extinction of marine life species that is taking place off the US west coast. Nobody in the media is talking about this as it is very much likely connected to the release of nuclear pollution into the water around Fukushima. You just need to look no further than the sea currents flowing from the Japanese islands and how it winds up the coast in the US and Canada," said Majia Nadesan.

The long standing and corrupt practice of "amakudari" -"descent from heaven" which led to the capture of regulators by the regulated in form of career revolving doors has made any meaningful reform a pipe dream. This ultimately allowed the Tokyo Power Company (TEPCO), Japan's largest utility, to defeat any efforts to improve plant safety as it would cost it too much money to comply with increased regulatory requirements. The ensuing legal fight kept the sea wall at 10 meters instead of increasing it to the height that would have stopped the tsunami in 2011 thus protecting the plant from damage.

TEPCO also used the lawsuit against the Japanese government to abdicate its responsibility to foresee the disaster and its fall out. As the problem of Daiichi melting reactors was taking on speed, TEPCO used its central position in the "nuclear village" to attack the PM Naoto Kan and to deflect its role in the crisis. As PM Kan ran afoul of TEPCO with his criticism of the company's actions while on site in Fukushima, TEPCO orchestrated a media campaign against him. It has twice spread false information about Kan's alleged interference with its operations, just to recant it when it was caught red handed. On the other hand, PM Kan has been more than willing to play a role of anti-nuclear industry "hero" while covering up its tracks and making it even more influential in the process. The endgame of it was nationalization of TEPCO as it could not be held responsible for financial liabilities due to its negligence and just like the US in its financial bailout; the taxpayers were left holding the bag.

Ironically the way Fukushima crisis transpired is very much reminiscent of the Soviet Union after the Chernobyl accident. Just as the Soviets did, the Japanese government quickly raised the “acceptable” level of individual radiation exposure to 20 millisieverts mSv/year contrary to the previous maximum “safe” exposure set at one (mSv)/year. Some medical professionals along with mainstream Japanese media went so far as to suggest that 100 mSv/year was a safe level of exposure which goes against international and commonly accepted norms set by science. This led to resignation of Professor Toshiso Kosako, an expert on radiation safety at the University of Tokyo and a nuclear adviser to PM Kan. In late April 2011 Kosako resigned protesting a decision that allowed “children living near the crippled Daiichi nuclear plant to receive doses of radiation equal to the international standard for nuclear power plant workers." Professor Kosako said he could not endorse this policy change from the point of view of science, or from the point of view of human rights. This happened under the watch of PM Kan and is contrary to his present role of anti-nuclear crusader while taking no responsibility for the action that as of today justifies and results in 150 cases of thyroid cancer in Fukushima children, annually.

The threat of evacuation of 50 million people due to multiple meltdowns has a certain imprint of fatalism that affected the population in Tokyo as well as it’s nearest biggest population center, Sendai. Located only 66 miles (111km) away from the 1.07 million metropolis, Sendai, has the distinction of being located just north of the plant in Tohoku plain. Contrary to the situation four years ago, the city has the appearance of a complete renewal if not outright amnesia about what happened in its suburbs to the east due to the tsunami and in the south in Fukushima. "I think our daily remainder of the situation is our economy as in our business we are at about 90 percent level of the period before the tsunami," said Naoko-san who is selling Japanese cakes at the small stand in Sendai JR station. "We have a lot of people from Fukushima and coastal areas living here but everyone wants to live a normal life so talking about it just hurts,” said Naoko-san. A similar opinion and ambiance is also present at the Sendai city hall which happened to have the only Geiger counter present in the city center that read 0.62-0.68 mSv in the span of about 1 hr. "We still have about one third of the people who came here in the period right after the disaster and stayed. Frankly I don't know if they are ever going back to lives they left behind as they are staying in both temporary housing and apartments throughout the city," said Koichiro Yokono, Director of Sendai's Post-Disaster Reconstruction Bureau. "As far as forgetting (the disaster) I know it is not a good thing. With every year and month the human mechanism is such that it wants to live life and forgetting is probably just a part of the life process, I guess," said Yokono.

The idea of forgetting and moving on also suits the political establishment as asking questions about the disaster also evokes questions about ultimate responsibility and, most importantly, if the lessons from it were ever learned. Judging from continued efforts to deal with the crisis that produces new releases of water and steam with unknown radiation contamination, the answer points to no. While the clean up, according to the Japanese government, to reduce the contamination level of the land and environment to 20 mSv/year has now concluded, questions remain about its effectiveness or even whether the job was done properly to begin with. According to a Jan 7th, 2013 report by New York Times, the cleanup has not been done properly as the best experts in technology; experience and capability were not hired. "Don't you think it is ironic that a company that was hired for the cleanup, Kajima Corporation (Japan's biggest construction company) was also the one that built the reactors in Fukushima to begin with? It is like letting them cover up their own incompetence and mistakes that might have contributed to the disaster to begin with," said Kato-san (the name given is an alias) who worked for over a year at the site building containment tanks for a consortium of companies hired by Kajima. "The whole thing was like a game to begin with. First they would give out propaganda about national importance of the project while in fact everyone was in it for the money. The job paid between 4500-5000 Yen ($36-40) per hour and we all did it for the money, myself included. We were suited up and as the process of putting it on with full gear and getting to site took about 1 hr. We worked in shifts with actual work time varying from 25 minutes to 4 hrs depending on level of radiation," said Kato. "I don't know if I will have problems from this in the future as it will take at least 10 years to show up and if there is anything (radiation) in me from this. Kajima was also in it for the money and the way they were logging us in at the site showed they also wanted to limit their liability as well. For example I have seen the log book that they are required to keep in order to keep track of who goes in and out of the site. But the entry is only general and it is the same whether one person goes in or a group of four as it was in my case. Tell me if this is not to cover themselves in case of anyone getting radiation sickness or cancer? We were simple workers but not stupid enough to not know why they did this that way and no other." he added.

The money train that was designated to deal with the aftermath of the disaster has produced a mini-boom in private contracting that was reminiscent of the worst excesses of US rule in Iraq and Afghanistan in the so-called "reconstruction" sector. According to the UK’s Guardian, the money spent was often the result of pork barrel politics in the Japanese Diet with the most egregious example of funds allocation to the Japanese whaling fleet to protect itself against international anti-whaling activists. Another way the money was spent was on PR that reinforced the well being of the population in affected areas, a truly Soviet-style like exercise in propaganda. Special attention was paid to cultivation of international public opinion in regards to the disaster and its aftermath. For example in Chicago in the United States, the Japanese Consulate General along with a bunch of its closely associated organizations paid for an annual propaganda program called "Kizuna" -"the bond". Instead of showing reality in post-apocalyptic areas of disaster, the Japanese government chose to put on a face of positive spin resulting in a bizarre collage of visual arts meeting old fashioned propaganda while cultivating local media personalities. In 2012, Greg Burns , the member of Chicago Tribune editorial board joined a pantheon of corporate pundits as Kizuna's "moderator" while Yoko Noge, Chicago-based reporter for arch-conservative Nippon Keizai Shimbun newspaper served as the Kizuna propagandist in 2014. "The displaced people in Fukushima are struggling while the government is blowing our tax money on useless projects that benefit cronies and parasites," said Mizuho Fukushima of the Social Democratic Party of Japan during a recent opposition rally in Tokyo. "It is unbelievable that our stupid government is giving money to South Sudan serving others' national interests while we have young mothers with children not having enough money to buy food," Mizuho Fukushima said.

Japan's disaster had huge international and foreign policy ramifications that went beyond pure humanitarian concerns. There have been series of conversations in the US government on a level of involvement of the US forces in Japan and the fate of its military bases if the country was to evacuate 25 percent of its territory due to the meltdown's worst case scenario. Politically this also became an issue of messaging as there was a presumption of radiation might affect US west coast to its east and as the cesium from Fukushima was detected west of Japan as far as Lithuania. The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission hid the real situation from Americans while trying to reassure the public that everything was fine.

In Britain the government together with the industry decided on a strategy to spin the information released to the public as to avert a backlash against nuclear energy experienced in Germany as result of the disaster in Japan.

In Japan the propaganda warfare took a more sinister turn blaming the victims for their predicament. Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun that is closely connected to Japan's ruling elite has run a series of articles on "radiophobia", attributing health complaints of the affected to psychological and emotional stress. Ironically the same took place during a period of “radiophobia” scare doled out by medical professionals and nuclear experts in the Soviet Union after the Chernobyl disaster. Their fears and concerns were met with explanation that the victims were subjected and suffered from fear of radiation rather than the radiation itself. University of California anthropologist Adriana Petryna’s ethnographic study of the Chernobyl medical assessment and compensation system shown it was biased against the victims and politically manipulated. The same now applies to the case of Fukushima disaster victims as the more sophisticated forms of manipulation employing intrinsically Japanese traits of shame and group think are now used to shift the effects of the disaster onto victims' own sense of responsibility. This allows the system to move on and not take responsibility for what transpired while using the cultural trait of the population's acquiescence as a catalyst for its de facto forced amnesia.

Looking at the Japanese media and governmental space that work hand in hand to obfuscate its responsibility to inform, the truth of the matter is : the technology to decommission melted reactors doesn't exist and the most optimistic scenario of final solution to the crisis is pure fiction.

As the country's political establishment is readying itself to host the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo for which there is no public money or popular support whatsoever, the nuclear sword of Damocles will be hanging over it. The negligence and incompetence bordering on willful disregard for lives of its citizens makes the Japanese government a perfect candidate for prosecution under the crimes against humanity statues. Its handling of the Fukushima crisis puts into doubt Japanese credentials as a real democracy that is able and willing to address its citizens' needs instead of using them as fodder for obscene corporate profits and foreign policy gamesmanship.

As a result Fukushima is worse than Chernobyl in many respects, making the difference between both political systems only a semantic one at best.

Japan Red Cross declined to be interviewed for the story.

Japanese Government did not respond to questions about its propaganda funding.

Chicago Tribune did not respond to request for interview.

Greg Burns did not respond to request for interview.

TEPCO did not respond to request for interview.

Japan Times did not respond to request for interview.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.