Is a return to peace in Libya really worth it?

“We will achieve peace, even if we have to fight for it.” American President Dwight Eisenhower’s famous words continue to resonate to this day.

Wars are triggered for no apparent reason, leading to ensuing chaos that ultimately requires peace to be restored, which in a tragi-comical way needs to be fought for.

If Iraq hadn't provided enough proof of this schizophrenic approach to war and peace, Libya would confirm it. Once Africa's most prosperous nation, Libya since the overthrow of Gaddafi at the hands of a NATO operation, has become a failed state.

In light of regional conflicts that have worsened since the Arab Spring of 2011, terrorists and human traffickers from across the globe are using its lawlessness to settle and thrive in what was once a secure and wholly stable nation.

And so the Western countries, led by Britain, have decided that in order to restore peace to the once peaceful nation, troops would have to be sent in.

The reality however is while wars are a hugely profitable affair, public opinion recoils at the idea of young men and women sent to fight in far-away lands for reasons difficult to justify and which inevitably means some returning in body bags.

The solution has therefore been in the far more palatable alternative: Mercenaries fished out of impoverished countries and sent to fight for minimal salaries. Should they be killed, the news will not be relegated back to Britain and the US and every party involved in the business of war will have benefited.

As part of the basic doctrine of supply and demand, Western powers are now creating the chaos for which they then supply the remedy.

Last month, a Danish documentary film maker revealed the use of African former child soldiers used by one notable 'security firm' chaired by British establishment grandee Nicholas Soames.

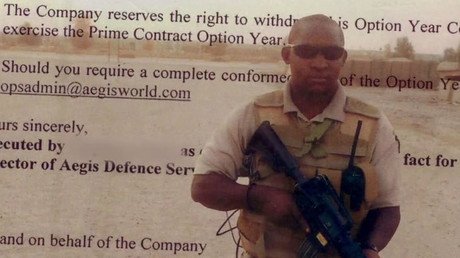

Soames is a conservative MP and former defense minister, he's also chairman of successful private security contractor Aegis.

Aegis' security staff have been present in numerous war zones including Afghanistan and Iraq and it was recently revealed that due to increasing costs the firm has resorted to former African child soldiers who were paid as little as £10 a day.

This startling revelation made by a British army officer points to the lack of principles associated to the security sector. African soldiers are perfect for these firms and the government that appoints them. They are cheaper to employ and their deaths will barely stir up negative emotions in the countries orchestrating the conflicts.

But what legal framework do these firms operate in? A national army is made up of professional soldiers signed up to the Geneva Convention. There are clear guidelines for these fighters to follow, should they fail in their mission they can expect to be court-martialed and even imprisoned. That is not the case for private security officers who operate under their own rules making them lethal killing machines with very little, if no, accountability to any order, not even their paymasters. Libya, now thrust into a vicious internecine conflict in which various outside elements have joined, is appealing via some of its 'official' representatives for help from those nations responsible for its initial destruction.

While there is little appetite for British 'squaddies' to be sent to their possible deaths in North Africa, mercenaries gathered from across third world countries are acceptable alternatives. As Britain conducts low key discussions with possible Libyan partners, security firms are waiting gleefully for the opportunity of making considerable amounts of money on the back of such chaos.

The question to be asked is about a conflict of interest. How can firms that are chaired or led by former or active government officials, who get to vote in favor of war, can then go on to profit monetarily from these conflicts.

The reality of course is that very few people are asking these questions, and since the dead won't be British, American or French, then the public will simply not be curious. British Afghan war veteran Joe Glenton recognized the “imperialist” approach to conflicts in Africa, Asia or the Middle East adding that “as long as those dying were in fact locals, very few people will look to take their governments or political leaders to task.”

The failure of African leaders to also object to the exploitation of vulnerable young men who'd suffered the traumas of war as children, and is now used to further the cause of war outside the continent, remains a stain on regional leaderships. In the absence of any form of debate, it appears that these security firms have healthy days ahead of them, and are in fact the driving force behind warmongering.

It's worth remembering that among the 'priority' missions for British troops entering Libya is securing oil wells whose production has been interrupted as a result of ongoing war.

While scores of Libyans are without water or electricity, and criminal gangs are holding entire cities to ransom, Britain's first call is to ensure oil output returns to some normality.

As the Arab saying goes 'pay him from his own purse', mercenaries sent out to Libya to restore some order will be paid from the Libyan treasury. In the absence of a fully functioning ministry administering the country's overall costs, expenses will therefore be taken at the source where oil revenue will be used to cover security firms' fees.

At this point it has not yet been revealed which firms will be working in Libya. Given the highly controversial nature of employing mercenaries these contracts are usually negotiated in total secrecy.

Firms such as Aegis will only boast of their presence in certain areas when their operations have been fully set up and working for several months if not years.

Libya for its part will not return to any form of peace in the foreseeable future regardless of who actually does the fighting.

Should British troops or mercenaries achieve significant results against various terror groups including the notorious ISIS, it remains unclear under whose authority the troubled nation would come under.

Ultimately that implies that an oil rich nation in constant turmoil is far more profitable in its current state than should it return to stability. A stable Libyan government will organize a professional army, regain control of towns and institutions and devote its resources to nation building.

A chaotic war torn country will provide work opportunities for countless security firms and corrupt politicians guaranteed a hefty pay check from the almost limitless hydrocarbon sector.

If I were a British politician with connections to the security sector, I know which option I'd go for.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.