Russian liberals hoped for an anti-Putin street revolution. They now may be realising that they wasted years on a doomed strategy

Russia's liberals have long hoped for a mass uprising against Vladimir Putin's government. But, as the president's support shows little sign of tailing off after almost 18 years in office, the revolution is nowhere to be seen.

Now, a number of developments, including an essay in Russia’s liberal-leaning flagship newspaper, Novaya Gazeta, suggest that some are finally recognising a new approach is required. Last week the International Council on Central and East European Studies held its congress, where I attended a roundtable on the topic of Homo Sovieticus – the “Soviet man” (or to use a more disparaging term, the “Sovok”).

Homo Sovieticus is a personality type whose overwhelmingly negative features are supposedly a product of the peculiar circumstances of life in the USSR, but who is said to have survived the collapse of the regime that created him. In the eyes of Russian liberals, it is the persistence of the Sovok, characterised by pessimism and love of authority, that is largely to blame for their country’s current problems.

The roundtable participants were all of the view that Homo Sovieticus is a myth and were left trying to explain why the concept enjoyed such popularity. One panellist even produced a chart showing how the use of the term had increased dramatically in the Russian media since 2014. Let me hazard an answer as to why.

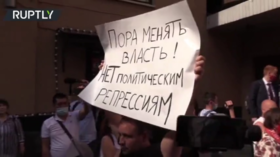

Also on rt.com Navalny ally Sobol leaves Russia after court ruling finds her guilty of organising unauthorised protests during Covid-19 – reportsUntil 2014, the prevailing view among Russian liberals was that the Russian state had been hijacked by a small group of crooks who had next to no popular support. The way to bring the hated “regime” to an end was through revolution – by mobilizing the masses and bringing a sufficient number of them onto the street.

The Bolotnaya protests in 2011-2012 boosted this mode of thinking. However, Bolotnaya’s failure and the huge surge of support for Putin that followed the 2014 reabsorption of Crimea forced a change in thinking. While a few oppositionists, such as Alexey Navalny and his dwindling gang of supporters, clung to the street protest formula, most were forced to recognise the reality that the government enjoys significant popular support. Consequently, they concluded that the problem was not a small band of “crooks and thieves” but rather the Russian people at large. The moral failings of the Russian people – i.e. Homo Sovieticus – provided a useful tool for explaining this phenomenon: thus the resurgence in the concept’s popularity.

This shift in thinking emerges very clearly in an article by London-based Russian academic Vladimir Pastukhov that was published last week in the liberal newspaper Novaya Gazeta. The shift is especially clear when one compares the article with another Pastukhov wrote for the same outlet in 2012. The contrast between the two is quite striking: the understanding of the government’s social base has expanded, while support for revolution has been abandoned.

To illustrate the point, let’s look first at Pastukhov’s 2012 piece, entitled “The state of dictatorship of the lumpen proletariat”, and then move on to last week’s article, “Spoiler of Russia’s Future.”

One of the interesting things about post-Soviet liberal intellectuals is that they retain traces of their communist upbringing, including a manner of looking at things through a class lens. So it is with Pastukhov. In his 2012 article, he argues that the state Putin has created isn’t just Putin alone. It has a “social base”, namely the “lumpen proletariat” - referencing the Marxist term for those uninterested in revolutionary change.

To Pastukhov, this is a mass of people whom the collapse of the Soviet Union left without any “corporative, moral, or legal ties”; it’s a group of “de-classed elements” who turned to crime for a living. This group seized control of the state, ruling over it as a “parasitic estate.” Russia was turned into a colonised country, whose resources were sucked dry by the colonisers, even though they were themselves Russian.

Expecting this system to evolve was pointless, wrote Pastukhov. Unlike Bolshevism, which was based on ideology, Putinism was founded on money – as long as rents continued to flow from the oil and gas industries, there was no reason for the colonial, parasitic, lumpen proletariat to change its ways. Eventually, of course, the rents would run dry and the system would collapse, but it would be best not to wait till then. The longer the parasites remained in power, the worse the situation would become, so that when revolution did come, it would be less of a paradigm-shifting revolution and more of a “bunt” (which has connotations of an anarchic riot).

The only way to prevent this catastrophe, wrote Pastukhov, was immediate revolution. “In current circumstances, revolution, which the Russian intelligentsia is so afraid of, is not an evil but a good,” he argued.

Such a revolution, though, could not immediately produce a democratic order. It would first have to seize power, destroy the existing criminal system, prevent “bunt” and maintain order. Only after the process of “decolonisation” and “decriminalisation” was complete could democracy emerge. Thus, concluded Pastukhov, “the path to democracy lies through dictatorship.”

There are some curious things about this piece. The talk of a “parasitic estate” governing Russia, which Pastukhov compares to a “virus”, carries undertones of Judeo-Masonic conspiracies, albeit identifying a different group as the guilty party. And the class-based analysis combined with the call for revolution and dictatorship have a sort of Bolshevik feel to them. It’s all rather illiberal and undemocratic. We’ll come back to that later, but in the meantime let’s move onto last week’s article for comparison.

By 2021, Pastukhov’s position has changed significantly. He sticks to the idea that Putin’s government has a social base, but his understanding of that base has widened enormously. No longer is Putin’s social base limited to the lumpen proletariat; now, it’s the mass of the Russian people as a whole. This is quite an important difference.

Thus, in his latest article Pastukhov writes that “Much of what we attribute to Putin should be attributed above all to society itself”. The key to Putin’s success, writes Pastukhov, is that “he never let the masses out of his sight, he followed their moods, and satisfied their desires.”

Bad Putin!

In this respect, says Pastukhov, Putin is like Joseph Stalin, who also supposedly paid close attention to what the masses were thinking. Pastukhov writes:

“Putin has remained so long in power because of a consistent and continually renewed social demand for his political course in the bowels of contemporary Russian society. The regime has always strictly fulfilled this demand, meticulously satisfying the real, albeit sometimes perverse, needs of the masses. In this sense, the regime is certainly a consistent successor of Bolshevik traditions in their Stalinist interpretation.”

OK, so, fulfilling the desires of the masses is Stalinism? By this logic, liberal democracy must mean a system in which the government does the opposite of what people want! Again, it’s a little odd. But the point is clear: Putin’s success rests on the fact that he listens to the people.

Indeed, argues Pastukhov, Putin is attuned to what you might call the “cultural code” of the masses. This, he says, consists of three main elements: “imperial vanity;” “an inclination to autocracy;” and “being accustomed to paternalism.” Homo Sovieticus, in other words.

Putting aside whether Pastukhov is engaging in gross oversimplification of the Russian character, the key point is that he thinks that this cultural code is deeply entrenched in the people, and there’s nothing much you can do about it. If you want to be politically successful, you have to play along with it.

And this, says Pastukhov, is where Russian liberals have gone wrong. They’ve taken the stance that patriotism is anathema and demanded, like the Maidan revolution in Ukraine, that Russia “join Europe.” But Russia’s absorption into some larger international whole is simply unacceptable to the masses. So too are neoliberal economics; the Russian people want a state that will provide their basic needs, and will always put that before democracy, individual liberties, and all the rest of it.

By putting themselves in opposition to all these things, Russia’s liberals have condemned themselves to failure, Pastukhov argues. In contrast to his 2012 essay, he rejects revolution. The masses just aren’t going to rise up against Putin, he says. Evolution is the only way ahead. The elites are divided between conformists and nonconformists. Things will change only when they agree on some compromise.

What will this consist of? The liberal nonconformists will have to accept nationalism, imperialism, centralised power and social-democracy in the place of cosmopolitanism, devolution and neoliberalism. Meanwhile, the conformists will accept democracy and the rule of law.

Also on rt.com West working to create ‘belt of instability’ around Russia by turning ‘brother against brother,’ says Moscow's top diplomat LavrovIn another Marxist-Leninist hangover, Pastukhov thus offers us a dialectical process: Russia will pass from the thesis of communism, through the antithesis of Yeltsinism/Putinism, to a new synthesis, which Pastukhov doesn’t define but might be a kind of “illiberal democracy” or maybe “liberal conservatism,” but certainly won’t be Western-style liberal democracy. As such Putinism is merely a “spoiler” for what will follow – which will be different from it but will still share some of its features.

Here’s where Pastukhov splits from his liberal friends. For most of them, the solution to Homo Sovieticus is to find a way to flush him from Russian society. Pastukhov instead urges them to give way to the Sovok, to ally with him instead of fighting him – in essence, to try to take Putin’s social base out from under his feet.

Pastukhov reflects a significant shift in liberal thinking, deriving from a recognition that the masses are not interested in following the intelligentsia on the path of revolution. The question is whether Pastukhov is alone, or whether others have come to the same conclusion.

His problem is that he is making quite a demand of fellow liberal intellectuals. Asking the intelligentsia to seek the support of the masses, to abandon dreams of revolution and of Russia’s integration into Europe, and to accept that whatever replaces Putinism will in some respects be a continuation of it, is to demand that liberals discard many of their most cherished beliefs. Will they listen? Personally, I don’t think there’s a bat in hell’s chance.

Meanwhile, speaking of bats, in separate news, one set a new record this week by flying 2,000 kilometres from London to Pskov. On arrival, however, this Western bat was immediately killed by a Russian cat. A fitting metaphor perhaps.

Like this story? Share it with a friend!

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.

The statements, views and opinions expressed in this column are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of RT.