How Ukrainians voted for the preservation of the Soviet Union in 1991, but still ended up in an independent state later that year

Back in early 1991, few thought the disappearance of the Soviet Union from the political map was likely. The results of a huge national referendum held in March indicated as much. Ukraine’s vote exceeded 70%, and public discussion of the joint future for all the socialist republics mainly focused on various forms of a federation.

Even the proponents of Ukrainian independence did not really believe this was within reach. But by August things started to unravel and, after a failed coup d’état in Moscow, Kiev proclaimed sovereignty.

Both the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic and its peers began to believe the collapse of the country was inevitable and had to be accepted as such. It was then that both Donbass and Crimea began to demand greater autonomy from the central government and more protection of their interests. In this article, RT revisits the six months between the USSR's landmark referendum and the independence vote in Ukraine that somehow turned out to be enough for the republic’s population to change their minds, and explores the reasons why this outcome both put an end to the world's largest ever country and sparked the separatist movement.

Looking for a Compromise

After 1988, a series of conflicts broke out one after another in different parts of the Soviet Union, creating a lot of tension: in Abkhazia, South Ossetia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and Transnistria, among others. In politics, at just about the same time, the “parade of sovereignties” began with the Estonian Sovereignty Declaration of November 16, 1988 that proclaimed the supremacy of Tallinn’s laws over those of the USSR. This was followed by a number of other republics, including the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic declaring sovereignty in 1989 and 1990, which in the end played a crucial role in taking the Soviet Union down.

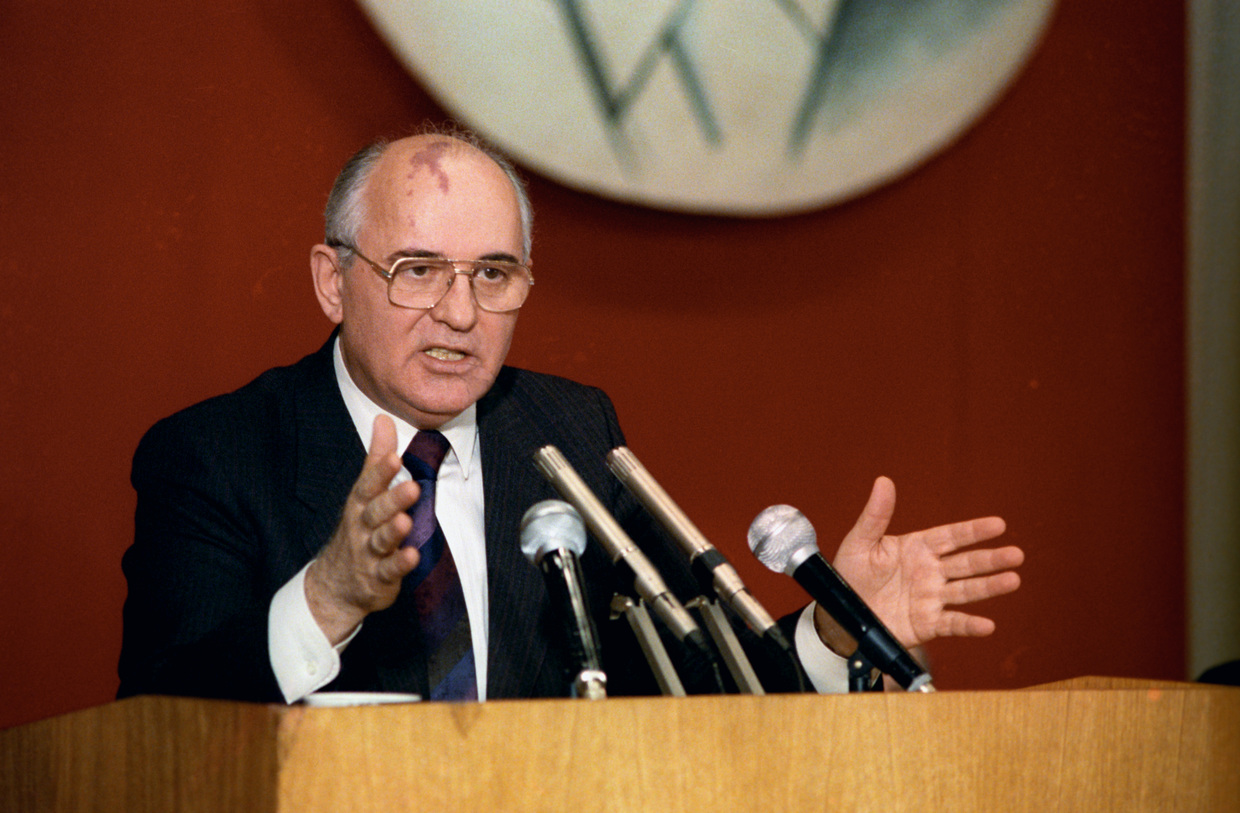

The ensuing struggle between Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev and Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR Boris Yeltsin led to the formation of an alternative center of power that ultimately was able to challenge the Kremlin.

The situation was spiraling and changes appeared irreversible. Lithuania became the first Soviet republic to declare independence, which was enacted on March 11, 1990 by the Supreme Council of the Lithuanian SSR. It became finally clear that all these years, the very existence of the USSR was based on a silent agreement between the republics’ elites. The agreement, however, was seriously shaken by a severe economic crisis triggered by a sudden removal of state monopoly mechanisms, as well as by the rise of separatist movements, plus ethnic conflicts and by a long-overdue need for political change.

In an effort to contain the situation, Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev proposed a New Union Treaty that would significantly expand the freedoms and rights of all the Union’s republics. In December 1990, the IV Congress of People’s Deputies, the equivalent of a parliament, voted to hold a referendum on the preservation of the USSR as a renewed confederation of equal sovereign republics and to pen a New Union Treaty. The idea of a confederation was proposed by the “architect of perestroika” Alexander Yakovlev. The proposal was put to a popular vote.

The 1991 Soviet Union referendum remains the only example of actual democracy in the history of the USSR. The ballot was set for March 17, 1991. Citizens had to answer “Yes” or “No” to the question: “Do you consider it necessary to preserve the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics as a renewed federation of equal sovereign republics, where human rights and freedoms will be guaranteed to all nationalities?”

A lot of criticism was voiced regarding the vague wording, which allowed the results to be interpreted very broadly. But for most Soviet citizens, the question presented a simple choice between the two options: they had to say whether they were for or against the existence of the Soviet Union. In the course of the preparation for the referendum, it became clear that the USSR as it was no longer existed, as Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Georgia, Moldova and Armenia had declared they would not hold an all-out referendum on their territory. There, votes were held in some designated areas: polling stations worked in a number of organizations, enterprises and military bases.

Some of those republics that agreed to run the referendum made changes. In the Ukrainian SSR, a supplemental question was added to the main one: “Do you agree that Ukraine should be part of the Union of Soviet Sovereign States on the basis of Ukraine’s Sovereignty Declaration?”The republic’s population was en masse not bothered by the inherent conflict within the wording, between the preservation of the USSR and the republic becoming its part as a “sovereign state” based on the 1990 Sovereignty Declaration. That can be easily explained by the fact that nothing really changed after sovereignty was enacted, except some attempts to introduce a new currency.

A total of 113.5 million people, or 76.4% of USSR citizens, voted for the preservation of the Soviet Union. The referendum showed that despite the growing disagreements, Soviet people wanted to continue living in one big state. 70% of the Ukrainian SSR’s population were in favor, and 80% said yes to the republic joining the union of sovereign states on the basis of the Sovereignty Declaration. In Ukraine’s western parts, around Lvov, Ivano-Frankovsk and Ternopol, however, the majority of the population voted against the preservation of the USSR.

It did seem at the time that Gorbachev had received the green light to go on with the reforms and get the New Union Treaty signed. However, due to the failed coup d’état attempt by the State Committee for the State of Emergency (GKChP), undertaken between August 18 and 21, 1991, to “stop the policies leading to the liquidation of the Soviet Union,” the New Union Treaty was not signed as scheduled. These events gave impetus to the disintegration process. In a matter of days, between August 20 and 31, 1991, Estonia, Latvia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova, Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan declared their independence.

Separatism Inside Out

Thus, the results of the Soviet Union referendum ceased to have any significance five months after it was held. The union’s republics moved on and held independence referendums, one by one. Eventually, on December 1, 1991, Ukraine declared its independence from the Soviet Union. The leadership of the Ukrainian SSR, which until then was still a Soviet republic and part of the Communist Party’s system, had spent those few months since the August 1991 attempted coup d’état waiting for the right moment.

Another factor that played a role was the fact that Gorbachev had Vladimir Ivashko moved from Kiev to Moscow as his new deputy. Ivashko was at the time chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR and head of the Ukrainian Communist Party. Gorbachev’s idea was to strengthen the ties between the leaderships this way and secure more support for himself in his fight against Yeltsin. However, the move backfired: Ivashko, who was a native of Kharkov in Eastern Ukraine, was replaced in the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR by Leonid Kravchuk, a Western Ukrainian, and this only accelerated the disintegration processes.

When the State Committee for the State of Emergency made its official public announcement of attempting to change the country’s political course on August 19, Kravchuk addressed the people of Ukraine on television with an appeal to “focus on solving the most important problems of the daily life of the republic” and to maintain peace and order. In a conversation with the then Commander-in-Chief of the Ground Forces of the USSR General Varennikov, Kravchuk gave an assurance that he would be able to independently maintain order in the republic.

With Yeltsin declaring himself Gorbachev’s “deputy” during the coup and acting like a de facto leader of the USSR calling for a “strong Russia,” Ukraine’s leaders realized that the time had come for decisive action. Events in Moscow triggered a lot of activity in Kiev. An emergency meeting of the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR was set for August 24. Deputies Levko Lukyanenko and Leonty Sanduliak wrote a draft Declaration of Independence overnight, but at the meeting it was decided the document was in need of major adjustments. A commission was set up to do this. Among its members were Alexander Moroz, the future head of the Socialist Party of Ukraine for many years to come, and Dmitry Pavlichko, who claimed that he had fought in the Ukrainian Insurgent Army (UPA is recognized as an extremist organization and banned in Russia) and was tasked to join the Komsomol and the Communist Party as an undercover agent for the WW2 Nazi collaborators in order to help sabotage the regime from the inside.

The final draft was a botched job anyway. Moroz later recounted how he’d proposed to remove any words of recognition of Yeltsin’s role from the text of the Declaration of Independence right in Kravchuk’s office: “After our meeting with Kravchuk, I said: let’s remove any wording about Yeltsin’s role in this process, because as time will pass, it will become just awkward. This is a historical document. Everyone agreed, we crossed it out and went to present it for the vote.”

The support was almost unanimous. Even the Communists voted for independence. “[The Communists] voted for Ukraine’s independence because they understood that the imperial games of power in Moscow could end badly for Ukraine, and because the precedent was already set by Vilnius and Tbilisi ... It all boiled down to who would take power, Gorbachev or Yeltsin,” Moroz, who would become chairman of the Verkhovna Rada of Ukraine, said later.

Confidence Vote

Nevertheless, most Ukrainians didn’t want to break up the country and sever economic and political ties with Russia – the two republics had close connections, including familial ones. At the March referendum that was held in the USSR the overwhelming majority of Ukrainians voted for keeping the Soviet Union. That’s why Kravchuk and his government needed to rally people’s support ahead of the referendum on Ukrainian independence to undermine the legitimacy of the USSR vote.

There was another factor that contributed to the success of this scenario – Yeltsin, concerned with staying in power, benefited from Ukraine’s declared independence and the referendum. It made signing the renewed Union Treaty impossible, which would inevitably strip Gorbachev of his power and throw him out of the equation in the eyes of the Communist Party elites, as well as regular Soviet people.

The plan of the Ukrainian authorities was successful. Almost 85% of registered Ukrainians voted in the referendum held on December 1, 1991. Only one question was asked – about the declaration of independence. The overwhelming majority (90%) said ‘yes’ to gaining independence. The numbers spoke for themselves. 83.9% of Donetsk residents voted ‘yes,’ 83.9% in Lugansk, 86.3% in Kharkov, and 85.4% in Odessa. Crimea had the lowest score in that respect, only 54.2% of people supported the independence scenario.

To this day, Ukrainian politicians use those numbers as proof that this was a time when the people came together in their nation-building ambitions. In reality, the overwhelming support of Ukraine’s independence even in the “pro-Russian” regions came as a surprise to many at the time. There were several reasons for the massive ‘yes’ vote, however.

First off, people were promised that all ties with Russia would stay intact and there would be no boundaries, cultural or otherwise, between the two states. The authorities also ensured the citizens that the Russian language would be protected. Kravchuk himself said this on a number of occasions. Nobody expected that there would be immediate borders dividing Russia and Ukraine. Subjectively, citizens of the two republics didn’t want a breakup, but they wanted strong power, which the Kremlin couldn’t demonstrate, so Ukrainians thought that there would be more order if the republic gained sovereignty. Many hoped that nothing would really change in the grand scheme of things, while Ukraine’s independence would result in its prosperity. Propaganda promised economic growth comparable to that of Germany and France. After all, before the fall of the Soviet Union, Ukraine was the European leader in steelmaking, coal and ironstone mining, as well as sugar production.

People were completely disoriented after the “parade of sovereignties” and August Coup. Another important factor is that the referendum was held at the same time as the presidential campaign, which Kravchuk won. Many didn’t necessarily vote for independence but voted for the “boss,” which was the usual MO for the Soviet people. These were the same people who said yes to keeping the Soviet Union earlier, in 1991. And nine months later they chose Kravchuk and Ukraine’s independence.

The referendum on Ukraine’s independence killed the scenario of an updated Soviet Union. The USSR soon disappeared from the map. In his comments on the referendum results, Yeltsin clearly stated that “without Ukraine, the union treaty would make no sense.” At that point, 13 out of the 15 republics had already declared independence and held similar referendums (Russia and Kazakhstan were the only ones that hadn’t done so). The events in Ukraine weren’t shocking, but they put an end to the dream of another union. Ukraine was the second most important republic and without it Gorbachev or Yeltsin had no union to rule over.

Cost of Independence

Nevertheless, even after the results of the December 5 referendum were announced Yeltsin met privately with Gorbachev to discuss the prospects of the Soviet Union. On the same day, during his inauguration, Kravchuk promised that Ukraine wouldn’t join any political unions, but would build bilateral relations with the former Soviet republics. He said that his country would be independent in its foreign policy and institute its own army and currency. The New Union Treaty was never signed, and on December 8, 1991, Belarus, Russia and Ukraine put their signatures under the famous Belovezh Accords, instituting the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS). This was the final nail in the Soviet Union’s coffin.

Later Leonid Kuchma, the second president of Ukraine, admitted that the Ukrainians had been misled ahead of the referendum: “We weren’t completely honest with the people when we said that Ukraine had been feeding Russia. In our estimates, we just used global prices on everything we manufactured, but we didn’t take into account the cost of products supplied by Russia for free. In 1989, our Economy Institute published a report about the Russia-Ukraine pay balance, and it ended up being negative for Ukraine. Ukraine paid for oil and gas less than for tea or water. The country was forced to sober up when Russia switched to the global prices in trade. This resulted in hyperinflation, the scale of which couldn’t compare to any other former Soviet republics.”

Already in the beginning of the 1990s local authorities began to realize that it wasn’t just the issue of economic growth that was presented in a misleading way. During the independence campaign, it was clearly stated that Ukraine would respect the rights of Russian and Russian-speaking citizens, that everyone would be equal and there would be no discrimination. At the end of 1991, Kravchuk promised that forced “Ukrainianization” would not be allowed, and his government would “take decisive action” against any ethnic discrimination.

In 1990, after the Ukrainian legislators declared sovereignty, the Crimean parliament scheduled a referendum on the peninsula’s legal status and re-establishing the Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. It took place on January 20, and 94% of Crimeans voted for creating an autonomy within the USSR.

However, Crimea didn’t turn into a conflict zone in 1991. The Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic even passed legislation granting the peninsula its autonomous status, but within Ukraine. Russia didn’t do anything about it because it was busy dealing with its own problems and the fight between Gorbachev and Yeltsin. The government of Crimea was also satisfied, since it got the right to its own constitution, president and guarantees for ethnic Russians.

However, Crimea was not the only region striving for autonomy – other Ukrainian territories also wanted political independence. The International Movement of Donbass lobbied for autonomous status for the Donetsk region, and it even had a scenario in which the Donetsk–Krivoy Rog Republic would be re-established. This was formed in 1918 as part of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and included the Kharkov, Dnepropetrovsk and Donetsk regions.

Ukrainian authorities were able to avert a crisis at the time by passing a law that criminalized activities aimed at undermining Ukraine’s territorial integrity – this could now cost a perpetrator up to 10 years in prison. The government also promised that the Russian language would be equal to Ukrainian in its state-language status, but this never happened; the legislation never went through, even though, according to Kravchuk, independent Ukraine “was going to be a state for Ukrainians, Russians and other ethnic groups.”

In the following years, Kravchuk, Kuchma and their successors in office greatly disappointed the Russian-speaking communities of southeastern Ukraine – especially in Donbass and Crimea. After a prolonged political crisis, failed promises to Russian-speaking Ukrainians and two major Western-backed street uprisings (the 2004 Orange Revolution and the 2014 Euromaidan), 22 years and 364 days after the first referendum, the Crimean Autonomous Republic held its last referendum, during which it chose to be reunited with Russia. The Donbass had fought for autonomy since 1991, and now it decided to follow its own way as well, different from that of Ukraine.