The last Tsar: How Russia commemorates the brutal communist murder of Emperor Nikolai II's family

On the night of July 16-17, 1918, the Bolsheviks shot the family of the last Russian tsar, Nikolai II. Eleven people were killed in total: The emperor, the empress, five of their children, and four royal servants. The remains were secretly buried in an abandoned mine, the location of which was hidden until the collapse of the Soviet Union.

The family of Nikolai II was subsequently canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church, and for the last 30 years, in mid-July, Christians from all over the world participate in a church procession from the murder site in Ekaterinburg to a monastery in Ganina Yama. An RT correspondent learned the story of this extrajudicial massacre and talked to pilgrims about their attitude to the Holy Royal Passion-Bearers.

In March of 1917, before the October Revolution, Russia’s provisional government decided to arrest the royal family. At first, the Romanov's lived at Tsarskoye Selo, but in August, they were forced to go to Tobolsk. In the spring of 1918, the group was moved to Ekaterinburg, where they stayed in the house of an engineer named Nikolay Ipatiev, which had been requisitioned by the Bolsheviks, and sometimes received food from the nuns of the Novo-Tikhvin convent.

On the night of July 16-17, 1918, Nikolai II, Empress Alexandra Feodorovna, Grand Duchesses Anastasia, Tatiana, Olga, and Maria, Tsarevich Alexei, imperial doctor Evgeny Botkin, imperial cook Ivan Kharitonov, the empress’ housemaid Anna Demidova, and the tsar’s valet Aloysius Troup, were all shot by Bolsheviks under the command of Yakov Yurovsky.

Shortly afterwards, the murder of the royal family was investigated by Nikolay Alekseevich Sokolov, a judicial investigator for particularly important cases with the Omsk District Court. The civil war between the Communists and their opponents was still raging in Russia in 1918. On July 25, anti-Bolshevik forces from the Siberian army occupied Ekaterinburg.

At the beginning of February 1919, Sokolov was summoned by the Supreme Governor, Admiral Alexander Kolchak, and instructed to launch an investigation. After the execution of Kolchak by the Communists in the winter of 1920, the investigator left the country and continued to take testimony from witnesses in Western Europe. In Paris, he interviewed Prince Lvov, the former chairman of the provisional government’s Council of Ministers, as well as its former minister of justice, Kerensky, and minister of foreign affairs, Milyukov.

Kerensky cited two main reasons for the arrest of the tsar and his family. The first was the “agitated mood” of workers and soldiers who wanted to deal with the sovereign. The second was “high-ranking officers” who thought the emperor and empress intended to conclude a “separate peace” with Germany.

Sokolov’s book entitled ‘The Murder of the Royal Family’, which contains materials from the investigation, was published in Berlin in 1925. He had been one step away from solving the mystery of whereabouts of the tsar’s remains but did not have time to discover them before the Bolsheviks took the area.

The key document containing details about the regicide is a note from 1920 written by Yurovsky, who had overseen the killing. According to his memoirs, on a night in July 1918, the royal family and their servants were told: “‘Due to unrest in the city, it is necessary to transfer the Romanov family from the upper floor to the lower one’… When the team entered, the commandant told the Romanovs that, since their relatives in Europe [probably meaning German troops under the leadership of the empress’ cousin, Emperor Wilhelm II – ed. note] were continuing their offensive against Soviet Russia… the [Ural] District’s executive committee had decided to shoot them. Nikolai turned his back to the team and faced his family. Then, as if coming to his senses, he turned to the commandant and asked: ‘What? What?’ The commandant hastily repeated his words and ordered the team to prepare. The team was told in advance who was to shoot at whom and ordered to aim directly at the heart in order to avoid a large amount of blood and end the affair as quickly as possible. Nikolai said nothing more and turned back to his family. The others uttered several incoherent exclamations for several seconds. Then the shooting began and lasted two to three minutes. Nikolai was killed on the spot by the commandant himself. Then, Alexandra Feodorovna and the Romanovs’ servants died immediately... Alexey, three of his sisters, the lady-in-waiting [Anna Demidova], and Botkin were still alive. This surprised the commandant, because they were aiming directly at the heart. They had to be shot again. It was also surprising that the bullets ricocheted off something, like hail, and bounced around the room. When they tried to stab one of the girls with a bayonet, the bayonet could not pierce the bodice. Thanks to all this, the whole procedure, counting the ‘check’, took 20 minutes.”

According to the note, the bodies were supposed to be buried in an abandoned mine nearby. However, shortly after the murder, it turned out that no one knew where it was, and nothing had been prepared to carry out the burial. In addition, the Bolsheviks were prevented from ending the affair as soon they wished, as the perpetrators of the murder made sporadic attempts to steal valuables from their victims. A car left Ekaterinburg with the bodies and stopped near the village of Koptyaki, where another abandoned mine was found in a nearby forest. The bodies were stripped and lowered down. The Bolsheviks tried to avoid inconvenient witnesses. They even announced in the village of Koptyaki that Czechs, who were armed opponents of the Soviet government, were hiding in the forest and that it would be searched. No one was allowed to leave the village. “The idea arose to bury some of the corpses right there in the mine,” Yurovsky writes. “They began to dig a hole and had almost dug it out when a peasant friend of Ermakov [who aided in hiding the bodies] drove up and it turned out that he could see the pit.”

In 2000, the monastery of the Holy Royal Passion-Bearers was established in the Ganina Yama tract. Some Orthodox consider this to be the final burial place of the royal remains.

Later, at a meeting of old Bolsheviks in 1934, Yurovsky described the vicissitudes of the burial in more detail. On the morning of July 17, water covered the bodies that had been put in the mine. They wanted to blow up the mine with bombs, but nothing came of it. They decided to “transport the corpses to another place.” Yurovsky instructed his subordinates to remove the bodies. “I had a plan, in case any problems arose, to bury them in groups, in different places along the roadway.”

Then they began to dig a new hole, but at some point, the already mentioned acquaintance of Ermakov saw it and the plan failed.

“After waiting for evening, we loaded the cart… It was already approaching midnight when I decided it was necessary to bury them somewhere nearby, since no one could see this place… I sent them to get railroad ties to cover the place where the corpses would be buried... About two months ago, I was leafing through a book by Sokolov, the investigator on extremely important cases, and I saw a picture of these railway ties. It says that they had been laid there to help trucks pass. So, after digging up the whole area, they didn’t think to look under the railway ties.”

While Sokolov was able to find traces of members of the imperial family near the Ganina Yama, he never found the bodies themselves.

“A bonfire was immediately lit, and while the grave was being prepared, we burned two corpses: those of Alexei and Demidova [in fact, Grand Duchess Maria – ed. note], who we burned instead of Alexandra Feodorovna by mistake. A pit was dug near the fire. We put the bones in and covered it. Another large fire was lit on top, and all traces were hidden by ashes. Meanwhile, a mass grave was dug for the others… Before putting the rest of the corpses into the pit, we poured sulfuric acid over them. Then we lowered them into the pit, poured more sulfuric acid on them, filled in the pit, and covered it with railroad ties. The empty truck drove over them a few times to tamp them down and that was it. At 5-6am, we gathered everyone and explained the significance of what we’d done, warning that everyone should forget about what they’d seen and never talk about it with anyone. Then we went to the city.”

In 2015, an investigator in the Prosecutor General’s Office of the Russian Federation named Vladimir Solovyov said that Pyotr Voykov had written out a purchase order for sulfuric acid. A metro station in the north of Moscow still bears the name ‘Voykovskaya’.

The imperial family’s final burial place under a platform of railway ties was not a secret for all Soviet citizens – apparently, high-ranking party functionaries knew about it. Literary critics believe that this place was even shown to the poet Vladimir Mayakovsky in 1928. The result of the visit was his poem ‘The Emperor’.

The first to discover the royal remains in Soviet times was geologist Alexander Avdonin, a graduate of the Ural Mining Institute. In the 1960s, Avdonin met Gennady Lisin from the Ural Worker publishing house. Lisin claimed that he’d been a member of the Boy Scouts and had helped White investigators search for the burial site in his youth. It was he who showed Avdonin Ganina Yama.

In 1976, Geli Ryabov, a screenwriter from Moscow and an honored employee of the Soviet Ministry of Internal Affairs, went to Avdonin. A few years later, Avdonin thoroughly examined the Old Koptyakov Road, along which the Bolsheviks had once transported the bodies of the Romanovs. In the town of Porosenkov Log near Ekaterinburg, he found the same railway ties. Under them, the geologist managed to find skulls and bones. Ryabov took two skulls to Moscow in the hope of conducting an examination. However, no one agreed to help him before the collapse of the USSR. Later, Avdonin and Ryabov decided to rebury the wooden box containing the remains near the place it was discovered – until better times.

In 1989, Ryabov told the Moscow News that he had found the imperial remains, and interest in the tsarist mystery grew rapidly among amateur geologists. Avdonin began to worry about the fate of the remains and wrote a letter to the chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the RSFSR, Boris Yeltsin, who instructed the governor of Sverdlovsk Region, Eduard Rossel, to deal with the issue.

In 1993, Rossel was briefly the head of the Ural Republic, a de facto entity in the Russian Federation that was not provided for by the Constitution. The governor believed that the Urals should become more independent in economic and legislative terms. In November, the initiative was finally curtailed, and Rossel was dismissed. Ural historians and journalists suspect that the governor may have been using the royal remains as a bargaining chip with the federal authorities up until that moment.

In 1998, after numerous examinations, the remains were buried in the Peter and Paul Cathedral in St. Petersburg in the presence of Yeltsin. At that time, the Russian Orthodox Church did not recognize the authenticity of the remains, and Patriarch Alexy II did not attend the funeral.

Among the discovered remains, two of the dead were missing. In 2007, a search team found the remains of Grand Duchess Maria and Tsarevich Alexei 75 meters from the main burial site.

In March 2022, ex-Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk, chairman of the Moscow Patriarchate’s Department for External Church Relations, stated that “We now have clear and sufficient evidence that the ‘Ekaterinburg remains’ are the genuine remains of members of the royal family… It seems to me that the arguments supporting the authenticity of the ‘Ekaterinburg remains’ significantly outwfeigh any arguments that could refute it.” The church could have officially recognized the authenticity of the remains at the Bishops’ Council in May, but this had to be postponed.

Sixty years after the October Revolution, Ipatiev’s house was demolished. Yeltsin was then the first secretary of the Sverdlovsk Regional Committee of the CPSU. In 2003, a Church-on-Blood was erected on this site, and in 1992, the tradition of holding a penitential procession was born. Its current route was established in 1994.

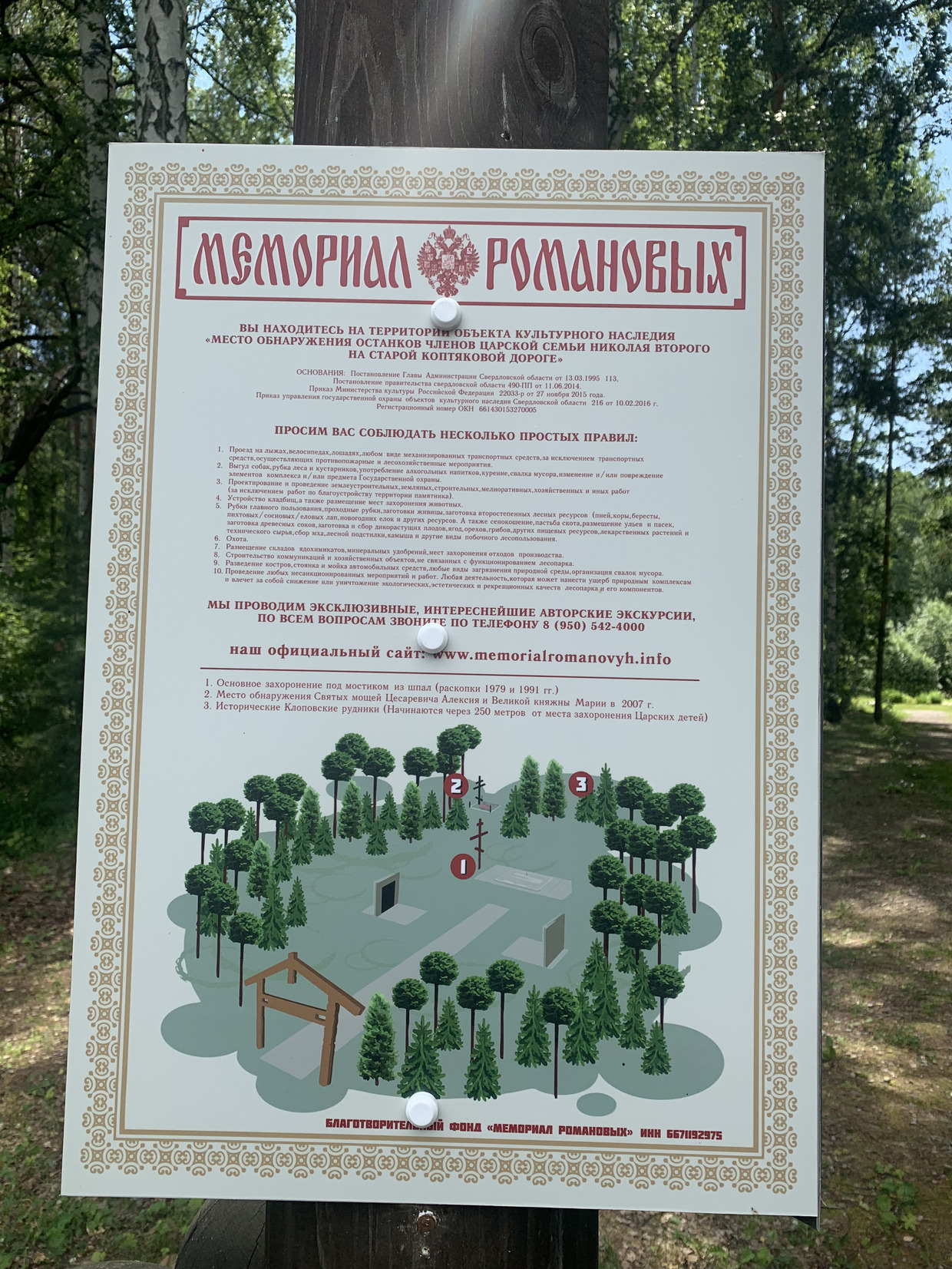

The Romanov Memorial is now located in the Porosenkov Log tract. Ilya Korovin, the director of the memorial, who is a supporter of Avdonin’s theory concerning the preserved remains, told RT that the procession route does not include this cultural heritage site.

In 2018, Patriarch Kirill participated in the procession. After four years, believers again walk around 20 kilometers from the Church-on-Blood to the monastery of the Holy Royal Passion-Bearers in the Ganina Yama tract. This year, there were 50,000 pilgrims, according to the St. Catherine’s Foundation.

In conversations with RT during the procession, believers shared their views on whether the Church should officially recognize the royal remains. Some believe this would be the right thing to do, putting an end to the ‘biggest crime’ in Russian history. Others, on the contrary, do not believe the remains found by Avdonin are authentic, holding that they were probably destroyed in Ganina Yama.

The procession begins at 2:30am Ural time. It is headed by church leaders, followed by a long column of Orthodox Christians, who hail not only from Russia, but also from Western Europe, Latin America, and Asia. In less than four hours, the first pilgrims appear at the final point of the route – the monastery at Ganina Yama. Orthodox Christians in comfortable sneakers carrying bottles of water cheerfully sing “Lord, Jesus Christ, have mercy on us!” The former mine is now enclosed by a gallery filled with portraits of the royal passion-bearers and their faithful servants.

RT spoke with people born in the Urals who say that they participated in the procession as children, and now help their elderly parents walk along this long route.